On the day before his 62nd birthday, my Father committed suicide. I’ve written pretty extensively about this in previous blogs. Needless to say, I sobbed. In fact, I broke. I was on emotional lockdown. I didn’t want to be around people. I didn’t want to talk. I needed quiet. Noise actually physically hurt. For the first time in my life, I understood what anxiety really felt like. I was hunkered down. Surviving. It had been almost a year. Around that time, a homeless friend brought a 10 week old puppy to my Mom’s house. It had followed him from wherever he lived - he would never tell us. But, our friend was drunk and this tiny, fluffy, adorable, little puppy was annoying him. So, he left it with my Mom and said she had to take him. Mom had a dog. Mom calls me. I go see it. I call my wife. Now, we have a dog. I should mention here that I am actually allergic to dogs - but the sweetness of this little animal was an antihistamine. But, wait. Ugh. What just happened!? I didn’t want a fucking dog! I didn’t want any new relationships! I wanted less. I wanted to be left alone. I sure as hell didn’t want to have to take care of some helpless little animal. I was having enough trouble taking care of myself at that point. I had swooned at this puppy’s cuteness and I regretted it immediately. But, then I started to love him - Augustus Buster a.k.a “Gus”. But then, within months, we were at the vet. Gus had severe hip problems, probably wouldn’t live for very long - at least not without severe pain. Goddamnit! I knew I didn’t want this fucking thing. This was all just a setup for more fucking loss and hurt and loneliness. I was furious. So mad at myself. So mad at the world. So mad that I had opened myself up to this little animal - this creature for whom we were already predicting his end-of-days in his first year. I sobbed. But, I also started healing. One of my first blogs about my Dad’s death was entitled “Living With Suicide.” Before I got my dog, I wasn’t. I was surviving suicide. But, when I opened myself to loving him, as painful and frustrating and scary as it was - as temporary as it might be - I began to live again. Today, almost 12 years later, we had to put my dog down. Cancer. I sobbed. I broke. I’ve not cried like this since I lost my Dad. I feel the horrible emptiness of losing Gus, but it has also pulled at something deep in the wounds from my Father’s death. I’ve thought about this day since that first visit to the vet. I knew it would be brutal. I knew my dog’s death was coming. But, I had no idea how badly this would hurt. I miss my dog. I miss my Dad. My natural instinct again today is to hunker down, but I can see my dog looking up at me with his big, brown, knowing eyes: “did you miss the whole point!?” Life and love are full of fear and loss and anxiety and vulnerability, but they are also the source of healing and peace and our connection to something beyond ourselves. Life and love take courage, but also create meaning. Death doesn’t take that meaning away. It reminds us of it.

7 Comments

Yesterday, my six-year-old daughter asked me why I put up two fingers as I waved to the homeless man selling newspapers on the corner. I initially explained that I was greeting him as a way of saying “thank you” for always waving and always sharing some positive energy as we sit in traffic at the stoplight. The guy does a great job. She pushed: “But, why do you put up two fingers?” Me: “It’s a way of saying peace to the person, but just using your hands.” C: silence Me (reflecting further): “And, it’s something Bugsy (her grandfather, my Dad) used to always do when he was alive. So, I guess I got it from him.” As she pondered my response for what was certainly only a couple of seconds, I was triggered, as I often am, into the flooding memory of my Father and to the realities of the things he instilled in me that I only sometimes recognize as his. Behaviors. Posture. Perhaps a penchant for cursing. My sister says my hands look just like his (I also happen to wear his ring every day). I am particularly aware of his legacy each April, the month of his suicide - April 27, 2006. I always try to write something around this time as some small effort in helping people know they are not alone in living with suicide. Their loved ones were not alone in their struggles with Depression, with sexual abuse, with religious-guilt-turned-self-loathing. These things killed my Dad, and have killed countless others. There are even more of us still living with them. My daughter persisted… C: “But, what is peace, Daddy?” Me (buying time): “Well, baby. That’s a good question…” I muddled through words like happiness and presence and contentment and safety – although I emphasized that it’s not necessarily about comfort. I spoke of its opposites of anxiety and worry and concern – even physical violence in terms I believe she is ready to understand. I stumbled. I repeated myself. At some point, she seemed to accept at least some piece of what I offered as an answer and she stopped pressing. I was less accepting of myself. My answer wasn’t wrong. It was just a mess. But, maybe there’s something in that reality that’s at the core of the idea of peace. In the quiet moments that followed as we continued down the street, my head again returned to my Dad. What a mess! His struggle. His contradictions. His love for others and hatred of himself. The pieces of me that are of him. My empty dreams of him holding my children. The stories and reflections I will share with my kids in hopes they might understand what may simply not be understandable. Will they get it? Will they get him? Will they be angry? Will they be confused? Will they care? Can they love him without knowing him? Can they learn from his life? From his death? Does it matter? And, once again, I returned to peace. My Father is no longer suffering – for me, for us – despite himself. I understand why he committed suicide. It’s all a big fucking mess, but, yes, I am at peace. He is at peace. My family is at peace. So, maybe at its core, peace is just something that lives deep within us and is not definable, recognizable, or understandable by others. Perhaps peace is as unique in definition as its possessor. Maybe peace is best understood as a personal journey and a process that we must commit to for ourselves, and can only hope for others to embark upon for themselves - and we wish them the best. Throw up the two fingers: Peace! So, perhaps this is a better, if still unsatisfying, answer to my daughter’s question: Me: I don’t know what your peace is, baby. I hope every day that I am doing my part to help you define and find it for yourself, deep within yourself. I hope one day when you are older and have lived through some of the brutality and brilliance that life can put upon you, that I can ask you the same question, and you will know what it means to you, even if you struggle with the words to express it.  I have been writing and thinking a lot about power lately. And, one of the principles of power that has surfaced is the idea that we are often most powerful when we feel most powerless. I explored this premise based on my own and my family’s experiences with my Dad’s suicide. It was the most broken, disorienting, unstable feeling time of my life. As I have written before, I don’t even remember a lot of what happened for a good year around that time. Yet, mostly thanks to my Mom and fully supported by my immediate family, we took the opportunity to tell our story, and to tell my Dad’s story. We shared publicly that his death was suicide, that he suffered with Depression, that he had experienced sexual abuse by a neighbor when he was a child. We thought we were being transparent for our own purposes and healing. It turned out that our transparency was of a far greater purpose and broader healing. We received literally hundreds of personal notes and letters (they continue occasionally over a decade later) of people sharing their own stories of suicide, Depression, and abuse. Some of these people were friends we had known for years but never knew shared these same experiences. Others were total strangers who had simply read the obituary and wanted to share their gratitude and their own story with people they knew would understand. It was incredibly powerful. We were powerful. My Dad’s life remained powerful, and even took on new power after his death. I share all of this again as I observe the Mayor of Nashville, Megan Barry, who recently lost her only son to an overdose, as she turns this most powerless feeling moment in her life into perhaps her most powerful. In fact, Mayor Barry’s being open and honest about her loss, her son’s struggle with addiction, and the frustrating and futile need and desire of a parent just to ask her son “what were you thinking” could be the most important work she has ever done. I know there are parents all over the country, and even the world, who have already read her story, listened to her words, and feel just a little more whole because of it. I know there are parents right now who will lose their child in this sort of tragedy, who have yet to realize how important the Mayor’s example will be to them. So, I guess this is in part at thank you to Mayor Barry, but also a note of encouragement to everyone else who feels alone, shamed about, or broken by their lives and the tragedies they have experienced. You are not alone. The more we can all muster the courage to share our struggles openly the more lives we can save, the more families we can heal, and the stronger communities we will build. We can and will be powerful in our most broken moments.  When we lose a music legend like Chris Cornell at a young age, the initial reports often describe the death as sudden or surprising, if there is any comment at all. “Cause of death” is rarely included – at least initially. Understandably, there must first be a formal investigation. For those of us who live with suicide, the waiting for cause of death, or ultimately the omission of a cause of death once verified, reverberate intensely. It has nothing to do with the deceased being a rock star. We feel that same omission, but without any expectation of more information to come, in the untimely obituary of the doctor or lawyer, the mother or husband, the soldier or veteran, the teenager – where no cause of death is mentioned. We fill in the blanks with our own experiences of suicide, Depression, abuse, addiction, and what it means to still be here when someone we love takes his own life. We know it’s complicated. We know people feel shame, confusion, guilt, and blame that exacerbate the incredible sense of loss. We know it is difficult to put into words. We know society doesn’t understand and doesn’t want to deal with our tragedy. We understand that omission – because it mirrors our own sense of loss. When we lose celebrities, however, there’s a different and more troubling pattern. As a society, we are quick to wrap celebrity suicide into a neat box so we don’t have to deal with the complexity of its reality. We summarize their deaths with a ready and familiar story – a cliché of the partying, addicted, immature, or otherwise angst-ridden, but privileged celebrity. Perhaps we even perversely glorify their deaths by throwing around words like “genius” or “artist” as if that explains it all away. Instead of the omission of information giving us permission to avoid reality, the cliché gives us such an exemption. No matter what comes of this story, we can do more to celebrate and extend the life and work of Chris Cornell today than going and downloading more of his music. We can talk about his struggles with addiction, mental health, and probable suicide, and try to understand him and understand ourselves in more complex, messy, deeply human terms. In doing so, we may actually give his life greater meaning than his music ever will.  I try to write something each year partly in remembrance of my Dad but mostly out of a commitment to being open and honest about his suicide, and what it means for me, and all of my family, to be living with suicide. I wasn’t sure what to write about this year. I wasn’t sure how to capture what it means to be living with suicide 11 years in. I wasn’t getting any lightening bolts of new insight or inspirations for how to communicate my experiences meaningfully. Today is the day. And then, this morning, around the time when my Dad ended his life, my family began circulating communications acknowledging each other and reminding each how much we love the other. So began my first tears of the week. Life is humbling, whether we are living with suicide or not. And, the relationships that both remind us to be humble and bolster us when we feel broken are our lifeblood. Being broken isn’t bad. It’s just being human. So, attempts to avoid or shield ourselves from being broken, or pretending we aren’t to some degree already are self-defeating. They are a front, hiding who we are from those around us, limiting our ability to touch the world genuinely, and preventing it from touching us. Acknowledging and sharing our brokenness and piecing ourselves back together with others is our greater calling – the pathway to our becoming more fully human, to developing relationships and lives that matter. As I reflected on the emotions stirred by my family’s messages, I realized that this is why. Living with suicide is about being broken. It is about a shared vulnerability and a responsibility to love and appreciate those who are also broken – all of us. We are all living with something. Wouldn’t it be nice if we just acknowledged this and met each other with a note of appreciation, love, and humility? Thank you for being broken with me.  Ten years before, I was a 20-year-old college kid with barely a worry on my mind. I was absorbed in the learning, new experiences, and…well…the self-absorption that often goes along with being 20 and a college kid. I was having the time of my life. Ten years after, I am a 40-year-old Dad, happily married, some semblance of a career, and two (mostly) happy, healthy daughters. My life is full and fortunate, even as I can get consumed by the weight of my responsibilities, and occasionally long for the opportunity to be self-absorbed again. I am having the time of my life. The temporal fulcrum for these reflections is my Dad’s suicide. I was 30, and, candidly, don’t remember much about my life at that time – at least for a year or so. It’s all a bit scrambled. (I have written more about my experiences in previous blogs.) As I reflect this year, however, 10 years out, I am drawn to the memory that we often celebrated my Dad’s birthday by watching the Nashville marathon, which happens to run right by our house. It’s always within a few days of his birthday. We aren’t a “running” family, but we would gather a blanket and some food and have a picnic in celebration of Dad and in awe and inspiration of the runners who passed us, roughly 20 miles in. This late in the race, some runners are still cruising along just fine, but others are hitting a wall. You can see the stress on their faces. You can see bodies slowly breaking. Some are even bleeding. You wonder where they are going in their minds to overcome the trauma of their bodies. You wonder how they will ever make it to the finish line. And yet, most of them do, in fact, in one way or another, make it to the finish line. 10 years. 20 miles. In remembering my Dad, in living with suicide, I can take cues from these runners. Indeed, I have to run my own marathon (we all do). At times, I have relied on my body to take me places when my mind and my heart would go nowhere. At other times, I have relied on my mind to transcend when the trauma invaded my muscles and bones. But, like these runners, I keep going, keep running (hopefully toward my life and not away from it). Sometimes cruising; sometimes struggling. 10 years from now, I will hopefully still be running this marathon. My pace may change. The mental and physical tools I rely on may evolve. But, I will be running. There is no other choice. I want no other choice. I will be 50. It will be the time of my life. “I love you, but I hate myself.”

…but I hate myself…but I hate myself…but I hate myself… This is the refrain that has again wrecked my mind over the last 24 hours. It started echoing in my brain when I saw the first article announcing Robin Williams’ suicide. I don’t know why this one has gotten to me so. I have hardly heard anything else today. It has stolen my focus. So, I am writing here to give it its due. This was the last phrase offered to my family and me from my Father: the last communication, the last line of his brief suicide note. He told us each that he loved us, but that he hated himself. The horror and sadness that someone who loved him feels at those words is beyond my ability to express. I know it’s what family, friends, and fans of Robin Williams are feeling today. Our imaginations try to grasp life, love, and relationships under that sort of shadow; self-hatred tainting everything you do, see, are. A mind that doesn’t know Depression simply can’t comprehend. We cry for his suffering and its contradiction to the joy he provided. I cry again for my Father’s suffering and contradictions. I am amazed both lived as long as they did. And strangely, my Father’s final written words provide some comfort and explanation for why we arrived here in mourning, in loss, in confusion. They articulate that he could no longer face himself, even as he faced the world with such love and ferocity of spirit. I sat with him just the week before as he sobbed uncontrollably wringing his hands and apologizing for things within – no connection to my reality as his son. It was that spirit within. It’s not that it was dead; it was corrupt, vicious, and destroying him from the inside. His suicide was the only way he saw left to rid himself and the world of that darkness. I find peace in my firm belief that my Father was at peace, not only upon his death, but in the moments leading up to it. He was resolved. He had clarity. He knew his suffering and his perceived burden on his family and the world were almost over. He had no fight left and he could see the light. “When I die, hallelujah by and by, I’ll fly away.” He was free, finally. On sunny afternoons this Spring, my older daughter (2 years old) has begun, in her own dialect, to ask to go play in the park across the street from our house, the house where I grew up. I’ll be honest, it is an almost impossible request to deny, no matter what the day has been like.

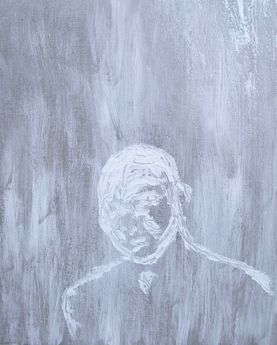

My daughter’s name is Charlie. She also loves to read (as a 2 year old reads). One day in the not-too-distant future, however, she will stop and actually read for herself the plaque that sits by the bench at the corner of the park closest to our house. Perhaps before any other words, she will recognize her name. She will see Charlie Williams. I look forward to that day in many ways, and yet have no idea how I will get through it: the connection made. The plaque and bench are dedicated to my father, her deceased grandfather, for “protecting the spirit and diversity of East Nashville.” I can already see the pride fill her face and the confusion to quickly follow. “But, I am Charlie Williams.” She will not understand the potency of her words, the spirit she will claim, and the responsibility she will begin to share. It will not happen on this particular day, but the process of understanding the pain and beauty of the world will certainly begin this day. And, someday when she is much older, she will want to know more about this plaque and this name that is hers. Someday, we will talk about Depression. Someday, we will talk about sexual abuse. Someday, we will talk about suicide. Someday, I will explain the month of April: the month my Father ended his life one day before his 62nd birthday, one day before the celebration of his birth. Strangely, these are the conversations I feel comfortable with. I know how to have these now, and am committed to having them with whoever will listen. It will certainly be different, more difficult, this time, but it will also be special. What I don’t know is how I will convey the life that was so much more important than the brutal moments that scarred it, or the mental illness that ultimately claimed it. How will my Charlie understand the depth and contradiction, the beauty and the darkness, the love and the spite that were her grandfather? How will she know him as a Father through me and my siblings, an in-law through my Wife, a husband through my Mom, as a friend and respected adversary through countless others? How might she someday find herself reflected in these stories? Find her own relationship to a namesake she will never know? Will she struggle or excel in ways that he did? I don’t know the answers to these questions. It is bigger than me. It is bigger than stories of a person, of a life. It is about connective tissue that must be generated, questioned, broken and reconfirmed over time. It is the iterative process of understanding where you come from and what that means to you. I guess she will figure it out. I guess I will figure it out. Someday in April, Charlie will know the world in a new way, and, I can only hope, will spend her lifetime seeking to understand it.  In September at my alma mater Wake Forest University, I am having my first solo art exhibition in almost ten years. What is interesting is not that I am showing my artwork again, but how these paintings came about and why. I could have never guessed ten years ago that I would be making this artwork. Six years ago, I would have never guessed I would be using these words to discuss it. I have written before about my Father’s suicide on April 27, 2006 and have talked a bit about the coping process I continue to work through. But, interestingly, creating artwork was not a part of that coping process – at least for the first three years. My artwork for several years up to 2006 had been technical, analytical, philosophical, and intentionally cold and emotionally vacuous. After Dad’s death, I was not sure what creating artwork really meant to me anymore. I would rather just work in my yard, on my house, or do something else “practical” with my time. For three years, I did not paint a thing. I entered my basement studio a few times, but I just stood there and looked around and was not compelled to engage. In retrospect, I believe all of my creative energies were focused on reinventing my self, getting to know my self, getting to know the world in a state that did not include the physical presence of my Dad. I had nothing else creative to give. Then, in 2009, I went to New York and saw an exhibition of paintings by Francis Bacon. I came home. I started painting. It was as though I had no choice. I couldn’t explain it. There were no words. I had three years to reflect on. The painting process was cathartic. But, it also became sociological, philosophical, and psychological. I had fun. I made a mess. I cried. I laughed. I cranked Godsmack and Metallica. Intensity. I blasted Hank Jr. and Willie Nelson. Longing. I boomed Disturbed and Rage Against the Machine. Anger. I meditated with Pearl Jam. Indifference. I lost 6 and 8 hours at a time rarely acknowledging my self, exhausted from three years of reflecting on my own existence. I just dialogued with the materials; they told me as much about where to go and what to do as I did them. I had no plan. I had no vision. It just kind of started happening. As the process gave way to discernible thoughts, I began reflecting on my experience of loss and the physical and mental challenges, paradoxes, dislocations, and general contradictions of the trauma and reconstitution of it all. I wake up one day and my mind is ready to head into work and is energized to get back into the mix; my body feels like I have been hit by a truck. I wake up another day and am ready to start exercising, eating right, and getting my body back working for me again; my mind wants me just to go back to sleep or just isolate in hopes that tomorrow it will feel clearer and more focused. I can read again, but I don’t want to talk about it. I can laugh again, but only around those I am most comfortable with. I can work again, but not in the same personal way I used to be able to. I am re-forming. Back and forth, on and on, my mind and my body distinguished themselves and their own mourning patterns and needs. I had no real control. It was a dissonance I had to learn to live with. By the time I started painting again, I didn’t need to tell anyone; I just needed to “talk” about it. I didn’t need anyone else to understand. I just needed to get something out. These paintings were for me. They were about me. They were about living. There were no words. As I finished new paintings and propped them up in corners and against walls, my studio became a chorus of new friends and philosophers, each talking with me and helping me explore further. Some had bad ideas and needed more work; some felt transcendent; others sat silently to speak to me another day, or perhaps never at all. And now, I will put them out there for others to see, for them to have their own dialogue with my internal experiences and external manifestations, to interpret a language that I have created for myself and that was never necessarily intended for them. Some may judge and despise them. They don’t speak to them. Some may be engaged and ask questions. They provoke them. Some may be moved and be unable to say why. There are no words. I am conflicted in acknowledging that these paintings were for me and yet now desiring for someone else to find meaning in them. This is why art matters. Francis Bacon didn’t paint so that I might cope with suicide. He did it for his own reasons. And, while I am certainly no Francis Bacon, I now put my work back out into the world and wonder if it just might speak to someone when there are no words. I have written before about my father’s suicide (see “Living with Suicide”) and I am doing so here again on the 5th anniversary of his death. I share this with you out of my commitment and my family’s commitment to doing our part to make sure that people struggling with Depression and issues related to sexual abuse, and those who love and support them, need not do so in the social and cultural shadows. I do not pretend that my words have such power. But, I do know from responses to my previous blog and to my family’s candor about our own experiences how just talking about something can help lift years of heavy, silent burden.

Now that I have that out in the open, I want to re-state and correct my first sentence. I am not writing this for the 5th anniversary of his death; a commemoration of a tragic moment, but certainly not the culminating symbol of almost 62 years of his life. I am writing because his life is worth celebrating regardless of when or how it ended, his death worth learning from, and the ongoing life of those who loved him worth living guided by how he lived. In living with suicide, I could count the years of life with my father that were “taken” from me by his actions; or, I could count the 30 years of love and support that were given to me. I could count the number of friends and family members hurt by his decision; or, I can count the people who are still around to share in his memory, carry on his spirit, and celebrate his life. I could count the number of years since his death, count how old he would be this month, or count the time since I had to begin my life again without him. The fact is that I can count this experience in any way I choose. So, here is one way I choose: Day 1: 4/27: I take a day to reflect. This day is not an anniversary to count in traditional ways but a dedicated time to look at myself, my family, my life and my father’s life (not his death). In reflecting: I smile. Strange and uncertain tears well up in my eyes as pride and loss and love and gratitude push them and me beyond our collective threshold. It is a sad smile, but a smile. I laugh. Echoes of his brilliance and his crassness remind me of the paradox and dichotomy of a man so loved by so many, and yet who did not love himself. I hear his laugh. I hurt. His psychological pain and his endurance for most of his life, and certainly all of mine, exhaust me and his strength and survival for my sake and for my Mom and my siblings overwhelm me. I hurt for him; I hurt for my Mom, not me. I isolate. There is fullness in quiet solitude that is the honest source of who we are. I continue to look for myself in light of my experiences and his. Day 2: 4/28: I take a day to celebrate. This is not about a birthday, but a life that like all of ours started at birth but does not end at death. It lives with those it touched. In celebrating: I stare. What am I really feeling? I try to be fully present with it all. I try to stop analyzing. I smirk. His attempts at being a curmudgeon were rarely successfully hidden behind his own smirk and a wry twinkle in his eye. My smirk looks a lot like his. I plant. His yard was a safe place for reflection and a place to grow something new and something of beauty. I plant something every year as a symbol of a life beyond our selves and one that I did not create nor can I end. But, one that I can certainly live. I connect. In the struggle to celebrate amid the echoes of the deepest pain, my family and friends provide the vehicle to transcend; to create wholeness. I gather with my family as we share our love and support and memories. We find comfort in togetherness (and food!). Day 3: 4/29, I start life all over again. I move forward with what is and work toward what can be in my own life, my work, and my relationships. In starting over: I breathe. In taking the deepest breath possible, I literally can feel my capacity to move forward and, as the oxygen floods my blood stream, strength returns to my body and hope to my soul. I cuss. I can only say that I’m my Father’s son, and a well-placed, loudly articulated f-bomb sometimes is just what I need to snap back into life. I relax. I return to myself and feel the presence of my life and my sense of who I am and know that I have been given a great gift. I live. These three days are in fact a gift. In the reflections and relationships and pain and joy of these three days, I have found and experienced the fullness and intensity of being human. Humbled, broken, proud and powerful. Sad, hollow, thankful, and full. It’s all there. 27-28-29. Three days. 72 hours. 62 years. So, in case anyone was wondering, I do not dread this time of year; I do not dread the memory of my father’s death; I count on it. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed