|

How to understand the advice we get as entrepreneurs (and what to do with it) is perhaps the most important topic that 2019 has left me wrestling with. There’s so much more to be written and explored, but I wanted to get something down to help organize my thoughts before 2020 is fully upon us.

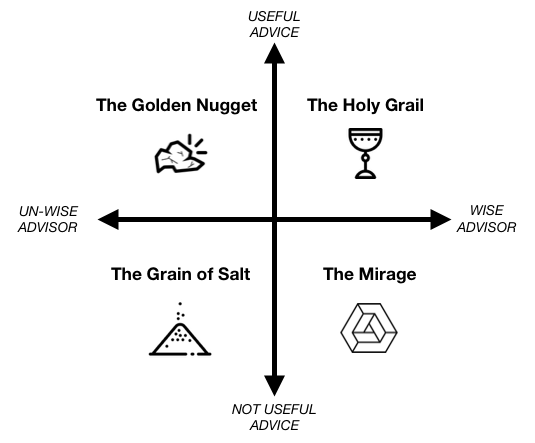

Here’s the confusing reality: Wise advisors can give wise advice, but wise advisors can also give un-wise advice. Un-wise advisors can give un-wise advice, but un-wise advisors can also give wise advice. So, what are we as entrepreneurs supposed to do with this? For starters, we need to sort advice and advisors into impermanent buckets so that we can focus and be most efficient with our learning at a given time, for a given stage of our company, or around a particular challenge or opportunity. The quality of advice and advisor can change based on context, so these categories should be at least somewhat fluid. To be clear, however, some people will likely stay in their buckets permanently. Here are a few ways to think about sorting advice and advisors: The Holy Grail This advice is hard to come by. There just aren’t that many people in the world who have the wisdom (which fundamentally includes their own self awareness) required to give good advice. Additionally, there just aren’t that many people who can listen to and understand our problems dispassionately and with the ability to help us identify the structural patterns and problems at the root of our issues or opportunities. If you find this person, hold on to them. When you get advice from them, dissect it, explore it, come back to it, let it marinate - and, ultimately, make sure it’s not The Mirage. The Mirage This advice is easier to come by than I ever realized. And to be clear, in my experience, it’s rarely - if ever - malicious. In fact, it often comes from wise people with a genuine intention to help us. For this reason, The Mirage has all of the appearances of The Holy Grail. Determining the difference has everything to do with our own understanding of our business, our needs, our questions, concerns and so forth and our ability to think critically about advice in that context. The trick of The Mirage is one of convoluting the value of the messenger with the value of the message. The Golden Nugget This advice is the fundamental reason we must always listen for understanding and keep an open mind. It’s the reason we must remain hungry as a learner, no matter who we are talking with. Just as we can’t accept advice simply because of the person who offers it (The Mirage trap), we should not dismiss advice out of hand for the same reason. It is potentially the person who knows little about our business or our product who can offer an insight that breaks us out of being stuck or sheds light on our next move. They might not even realize that they are giving us advice. We just have to listen for and grab that Golden Nugget when it shows itself. The Grain of Salt Again, I’m not trying to be ugly here but just strategic in how we think about advice. This isn’t about individual people. Sometimes advice just isn’t relevant. Sometimes other people’s experiences, views of the world, or approaches to problem-solving just don’t match our own personally or in terms of our business. It’s OK. Just know that. Be nice. And, file this advice away somewhere. Still, I’d say to archive it, don’t delete it. Who knows, we might find in time that it ends up a Golden Nugget.

0 Comments

I generally try not to write about a topic that’s already been exhausted by countless other blogs, videos, talks, etc. but sometimes I get bold enough to think that I might add just one more re-frame that might, just maybe, help to simplify a topic that has been over-wrought, over-written, and most importantly over-thought. What I’ve found with product design - as with most things - is that it doesn’t matter how many tools you have at your disposal, how many blogs you’ve read, frameworks you follow, or videos you’ve watched. If you don’t have the foundational mindsets to apply them well, then what you build will check all the boxes and deliver little of the value. So, I’d like to strip the topic of human-centered design down to three basic mindsets - and then Google can tell you everything else you need to know about how to actually do it. Mindset #1: Be Human. You are a human being designing products for other human beings. (I warned you I would make it basic.) While this is a painfully obvious statement, it’s also often ignored in product design and is a chronic reason for product failure resulting from lack of adoption. I spent many years in education and in healthcare - both in technology and not. The number of products and services in those two industries that are designed to facilitate those two industries - not the people working in them or the outcomes they are supposed to achieve - is one great driver of their continuing bureaucracy and inefficiency. In education, we build tools and strategies for tracking student risk indicators but do little to design tools and processes to increase student engagement, mental health, or otherwise. In healthcare, we spent countless billions of dollars to manage and make sense of patient healthcare data but invest relatively little in helping people access healthy choices and manage their own health and wellness. So, what are we trying to accomplish and for whom? To remain human in our product design, we must:

Mindset #2: Be Humble. You don’t know everything and, if you work hard enough, you will probably find out that you don’t know very much at all. This is a good thing, not a weakness. In fact, after a dozen years in education and youth work and having co-founded a company building a software product based on that experience, I became a much better product designer when we pivoted the company to healthcare and I actually didn’t know anything at all. All of my experience and previous knowledge in education wrongly gave me the impression I had all the answers and made me less curious about what people thought their problems were - and less honest about what they would actually be willing to do to solve them. In healthcare, I knew it was learn-or-die for our product and our company, so I approached product design with more humility. To remain humble in our product design, we must:

Mindset #3: Be Hungry. If you aren’t deeply, personally motivated by the creative, iterative process of product design, you will not be able to sustain human-centered design over time. Getting feedback from our users is difficult, often humbling, and at times humiliating. It’s a learning process and learning requires a deep desire to face and learn from mistakes - and not cover them up. Getting feedback on an early product is particularly challenging as we often try to explain away its known deficiencies more than listen to the feedback on what’s there. Our insecurity takes over. As I mentioned above, humans (meaning us) are emotional, but we have to be bigger than our own egos if we are actually going to solve real problems for our customers. In other words, our hunger must be stronger than our ego. To remain hungry in our product design, we must:

Feature Frenzy and its close cousin Shiny Object Syndrome (S.O.S) are startup killers. They confuse product direction, muddle the sales pipeline, and frustrate developers and eventually our users - and then, as a result, all of us.

And yet, we want aspirational and aggressive product roadmaps so that we can excite the market with our product vision, demonstrate responsiveness to early customer feedback, and possibly share our vision and direction to seek investment to grow the company. Sharing a big vision, being creative, and coming up with exciting and dynamic solutions are why we became entrepreneurs after all! So, the challenge is real. Recently, I pulled together a workshop on how to avoid Feature Frenzy but maintain an aspirational product roadmap, and here are 10 tips to consider: Keep your aspirations focused on your business first, not your software. Software should enable your business. New features (i.e. more software) should have clear and direct business value. See if you can test the business value first without building more software. It’s amazing what you can figure out with some conversations, some data, and maybe a spreadsheet. If that won’t cut it, just make sure you are building the smallest amount of software possible to test the business value. Be clear about the purpose of your roadmap. There are lots of roads and lots of maps that serve lots of purposes. So, you just need to be clear at all times which one you are talking about and who it is for. The roadmap for your tech team and the roadmap for your investors or your customers are not the same in detail or message - even though they should align in direction. Never forget: Products are for customers, so your roadmap should take them somewhere. Entrepreneurs like new things and get excited by the next thing. But, the milestones on a product roadmap should be focused on delivering some tangible value or specific outcome to your user. Beware solutions looking for problems. Entrepreneurs are problem solvers, so we come up with solutions. New features can be dazzling for us and for our customers, but a pile of new features that seem like a solution to us doesn’t necessarily solve a customer problem as they understand it. A startup product roadmap should focus on finding answers to critical market hypotheses. Our early product development priorities and sequencing should lead to validating or invalidating the hypotheses that are core to early adoption. If it includes anything else, it’s probably noise for you, your team, and the client and will obfuscate the testing of the value proposition. It’s easy to come up with features customers love, but a lot harder to build a product they will actually use. Beware solutions to problems that are nice-to-solve but don’t need to be solved. Ideas and feedback from the market on what’s nice-to-solve often comes clearer and faster than the underlying what-needs-to-be-solved. We have to dig deeper into our customer problems than they are able to and come up with solutions they don’t have the time, inclination, or experience to create for themselves. Be aware that users who say email is their problem will often design email as their solution. I have lived this one many times trying to improve communication in schools and in hospitals. Don’t ask customers for solutions. You have to dig into their problems, listen for understanding, and solve from there. Beware the shiny object. When you see it, check your reflection in it before you grab it. Figure out why you think you need it. Just say no. We have to communicate that we are listening and care about our customer feedback even when we don’t take it. But feedback like: “If your product just did X, we’d be ready to buy” or “If you just added this button, we’d start onboarding all of our users” is almost never true. If we chase those things, we will almost certainly kill our product. Be honest about what you can deliver and when - and then deliver it. Overselling puts our product roadmap in chronic debt and is a sure path to disappointed customers, frustrated product managers, and uncreative developers. Selling something small but valuable and delivering it is a win. Selling something huge and then only delivering that same small-but-valuable element becomes a loss. As a bonus, I highly recommend watching this video: 20 Years of Product Management in 25 Minutes by Dave Wascha Image: https://wavelength.asana.com/work-plans-high-level-objectives-roadmap-week/ |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed