|

I often lament in my own heart and mind that my more radical days seem to be behind me. What am I doing with my life and my upbringing? And then, there are other times when I think my radical waters may actually just run a little more deeply now - yes, more still with less activity agitating the surface, but perhaps with a wisdom and nonviolence I never knew in my more activist days.

The moment I regret that I don’t do work that is directly focused on social change anymore, I seem to find myself having a conversation about justice or equity or privilege or race or gender with my daughters (6 & 8). And, the more I have those conversations with them, with all the apparent complexity and history and economic underpinnings, the more frequently I arrive at a simple answer - a simple explanation - a simple premise: Love. This morning I watched from the sidelines as my kindergartener had her final class meeting on Zoom, replete with a photo slide show and original music by her exceptional teacher (who also taught my 8-year-old who loves her so much still that she sat in on the final class of kindergarten again with her little sister). The love of the kids for their teacher was obvious. They wouldn’t let her end the meeting. “Mrs. Scott, I lost a tooth.” “Mrs. Scott, my Mom was crying.” “Mrs. Scott, I got a haircut.” “Mrs. Scott, I got a puppy.” “Mrs. Scott…” Her students love Mrs. Scott. In turn, Mrs. Scott’s love for the kids is honestly somewhat profound. It’s not just that she is chronically kind and funny with the kids. It’s not just that she’s encouraging and seems genuinely interested or concerned when they tell her they have a hang nail. It’s not just the hours of work that went into creating her classroom and a wonderful virtual last class that felt warm and close even as it was remote. It’s not the tears she cried at her own video which she had certainly watched a thousand times while putting it together. Yes, of course, it’s all of that. But, it’s Mrs. Scott’s bold and radical and clearly articulated message in words and on the screen and in actions that said: I love you. She wrote it right there on the screen: I love you. She said it to all of those squirmy, smiling, doting faces in their little Zoom boxes: I love you. The kids know it. They know it down deep. And, this is why they read. This is why they work hard for her. This is why they want to be their best selves for their teacher - even when that often means all the repressed ugly comes out on the parents when they get home! I still appreciate that - most days. What more profound way could a child start her educational journey than associating it with being loved and with learning to love herself and to love others in her classroom and beyond - to love in a way that, in her kindergarten style, encourages her to make simple choices to build a more loving world with kindness and color and unicorns and chaos. Now, I’m not naive. I’ve been through school and I’ve worked around education. Sadly, this sort of overt and radical love does not last - at least not in this pure form. It lives here and there with those special teachers, but is not the first association most of us have with school. But, imagine if we built schools around the idea of love. Imagine if the love a kindergarten teacher gives her children was the same love given by an AP Biology teacher to a Senior in High School. Imagine if the love among peers encouraged in a kindergarten classroom was cultivated in Middle School classrooms. Imagine what school would look like! Imagine what our children would be like! Imagine what our society would be like! There was a time when I would have ignorantly suggested that this was some sort of naive vision for social change, that it was a nice thought for a Hallmark card, but hardly one bent toward radical social change. I was wrong. My belief today in love as the necessary foundation for change is more deep and more radical than any belief I have ever held. And, as I continue to read and learn, I understand more deeply how it is actually woven into the most profound and effective social change work in our nation’s history - and similar change work across the globe. This is not a new thought. It is not a unique thought. And yet, it is a thought we fail to keep, to protect, to live into, to remain committed to over a lifetime of education and learning. Myles Horton puts it clearly and succinctly and with an almost 90-year history of work at the Highlander Research and Education Center to prove it can be more than an idea. It can be put into practice. “I think if I had to put a finger on what I consider a good education, a good radical education, it wouldn’t be about methods or techniques. It would be loving people first.” We love you too, Mrs. Scott. Myles Horton, We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change

1 Comment

I think we parents need to take a deep breath and step back from the struggle of attempting to school our children at home and help our children’s educations emerge from the real, lived experiences we are all working through. We don’t need to try to be the school teachers we are not, but we can try to be learners and thinkers who reflect on our experiences and are resilient and empathetic and loving and kind, and we can model these lifelong tools and values for our children here and now. No worksheet necessary. Our children will not remember the classroom lessons they learned - or didn’t - in the time of the pandemic, but they very well could carry lifelong lessons in how we all treated each other and managed our way through it - human-to-human - even at a distance. So, to my children, here are some things I hope you are learning in these first several weeks of a new pandemic reality: Your education is far, far bigger than school. There’s a lot to learn during a post-tornado, pandemic-driven quarantine when you live with a senior citizen and have family member with chronic “underlying conditions”. And, while, yes, I want you to practice your reading and keep your math skills fresh, it is a very different kind of learning that will turn tragedy into possibility as your life unfolds. These are times that help illuminate who you are and architect who you will become. Your education is a lifelong process most deeply rooted in presence with whatever life throws your way. Every day matters, and you can’t count on tomorrow. Some days this means you throw caution to the wind, and some days it means you proceed with all due caution. Some days it means you get a puppy. It’s part of your life’s journey to gain the wisdom to know the difference. Your teachers love you. And, your teachers miss you when school is out. And, they are not only willing to do what it takes to deliver your lessons but will even call you on FaceTime and chat for half-an-hour like you are lifelong friends who just needed to reconnect. What you talked about was not the lesson to be learned. That they called is the lesson. Your teachers are creative. Joy and creativity and good teaching go hand-in-hand. Your teachers often work in settings that limit their creativity and steal their joy by focusing their labor on Education rather than enabling their work in helping students learn. Those livestreams and videos and conference calls for you and your classmates are your teachers doing their work in new ways because their work matters to them, to you, to all of us. Their creativity matters - your creativity matters - and school should never take that away. Your parents work hard. (But, that doesn’t make us great teachers.) We work hard because we love you. We work hard because we want to provide for you. We work hard because our work is part of our sense of who we are. Hard work matters, no matter what that work is. If you are going to do something, do it with all you’ve got. Help in whatever way you can help. When you see a difficult situation, ask yourself: how can I help? It doesn’t have to be complicated. But, your ability to help starts with understanding the gifts you bring to the world and figuring out where those gifts can meet the worlds’ needs. If nothing else, you can always be kind. You can always listen. You can always treat others with respect. Even if you can’t do anything, you can always say something. When you don’t feel like you can help or don’t know how, dropping a note or a text and just saying something like “I had you on my mind. Sending my love” is good for you and good for whoever you send it to. Difficult times can make us feel alone and powerless. Your words can help remind you and others that we aren’t. There’s always someone worse off than you. So, there’s really no time or use for complaining. When you think of the frustration of a pandemic and how bad that seems for you, you can also think of your friend and classmate who lost everything in a tornado just weeks before. If you will pause and open yourself to empathy, you will always find someone whose situation makes yours seem relatively manageable. Then, you can ask: how can I help? Friends matter. Our friends tell us something about who we are and where we’ve come from, and when our basic way of life gets disrupted and our sense of who we are and why we are comes into question, connecting with friends can be critically grounding. It matters even if it is virtual. Physical health and mental health are closely related. Getting up every morning feeling isolated takes its toll on a spirit. No amount of food or drink or vice of any sort can rejuvenate the spirit. Such things can soothe temporarily, but they cannot re-spirit us from the inside out. A few minutes of yoga, a walk, a bike ride, a short run, whatever it is - physical health doesn’t have to be long or complicated. Every little bit helps, and it helps our minds as much or more than our bodies.  We all know what a good teacher can mean in a kid’s life. We all have had those teachers who showed us something different, treated us as the special individuals we are, and shared their power so that we may grow our own. Good teachers change kids lives. Most of us are fortunate enough to know this first hand – some many times over, and for some maybe there’s just been one. What I didn’t realize, however, in my own educational experience and in all of my years as an advocate for and with students is what a good teacher can mean to a parent. My older daughter is finishing Pre K at McKendree Daycare in Nashville and her year in this class has not only inspired and helped her grow, but it has inspired and helped me grow as her parent. In this Pre K class, my 5 year old has learned to explore, to ask questions, to solve problems, brainstorm, work in groups, create, and delve deeply into topics of her own and her class’ choosing. She has learned to work alone and with others to define and refine those topics of investigation. She has practiced democracy in her classroom. There is joy in her classroom. She has in Pre K experienced all that I have ever advocated for in our middle and high schools. She has done this because she has a teacher who listens deeply and respects her and her classmates’ ideas and questions, regardless of their ages (or perhaps because of them). Her teacher has instilled inquisitiveness and validated her personal learning process because he exposes and models his own inquisitiveness and learning. Her class has never been about Education even as she hits and exceeds the necessary Pre K educational milestones. The educational curriculum is hidden behind a powerful learning relationship. My daughter and I laugh when she often starts to ask me a question by accidentally calling me her teacher’s name. What an extraordinary thing! He and her learning are so closely intertwined. It is also a motivating thing – that I may be a father who so models and supports her learning, inquisitiveness, sense of democracy, and so on. As she finishes Pre K and leaves this class, I feel anxious. I know what a special teacher and experience she has had this year. I am worried what the next 13 years of formal schooling and education systems will bring and how they will compare. But, at the end of the day, I can only hope for more good teachers. I know they are out there and I’m confident that we will have many more great experiences, that my daughter and I will develop many more powerful learning relationships as we navigate her formal education. For now, as we speak of her last day in the current class, it just feels like a leap of faith. So, I guess this is a note of thanks to Mr. Anthony and a prospective thanks to those great teachers to come. Please know how much we appreciate you and need you. Know that you have the ability to impact not only the life of your students but also of their parents. Reposting a blog about my book Creating Matters: Reflections on Art, Business, and Life (so far) originally posted here by Seton Catholic Schools' Chief Academic Officer William H. Hughes Ph.D. Anderson William’s book Creating Matters is gaining traction. We are using Creating Matters as a guide in the development of the Seton Catholic Schools Academic Team.

Creating Matters is helping us to think differently about our work as educators: our priorities, relationships, and what we are creating – in this case high performing schools and effective leaders. The world has always belonged to learners. Creating, building creative relationships, and purposefully reflecting can generate continuous learning and help us think differently about transforming a school, a business or one’s life. We have to think differently or we won’t grow and understand the changing world around us. Lifelong learning opens our minds exposes us to new vantage points, more things to see, to touch, to explore. Lifelong learning is hard work. It is not for everyone, but for those who commit, the joy and engagement makes one’s life better. To sustain lifelong learning, we must depend on our creativity. Creativity defines the nature of our relationships. It puts our learning into action. It is a philosophy of how we see the world and our role in it. Creativity will determine whether our efforts will ultimately create impact, whether we transform schools and build new leaders, and pass that work to a new generation. Creating anything new starts with asking questions: questioning the perceptions of the others, the sources of accepted fact; the thinking that verified it; and how we rethink the work of transforming schools from scratch. Too many schools and districts are great examples of organizations that have failed over time to recreate themselves while convincing themselves they are better than the facts show. In the case of Seton Catholic Schools, Creating Matters guides us in creating with a focus on what kids should be learning and becoming: creative, lifelong learners who are ready to change and engage in their community. Isn’t that what schools are charged with doing? Schools in transformation must ask this question: If we are starting from scratch and wanted the kids to become lifelong learners, is what we are doing now what we would design from scratch? Answering this question and wrestling with its implications require us to be more creative, to have stronger relationships that survive the necessary arguments and conflicts, and to build our work on a model of creating rather than constantly fixing. At Seton, we are seeing some bright spots in teaching and learning along with better student engagement with faculty who are starting from scratch. We are collectively creating and questioning our own assumptions, learning new skills and creating lifelong learning across our school community. When we bring this shared purpose and focus to our classrooms and students, the transformation is palpable. We are building a community of students, faculty and staff who are committing to lifelong learning and to creating the kinds of schools where that commitment is put into practice. Read Creating Matters and then put it into practice. This isn’t about “seven easy steps to a better you” or some other seemingly simple approach to creativity or leadership. It’s about renewing your awareness of who you are and what you can do when you commit to creating what matters in school, business, or most importantly, life.  This is the expanded Q&A interview with Anderson Williams that appears in Volume 25, No. 1 of the Youth Voice issue of the National Dropout Prevention Center/Network Newsletter from page two. Q: On Page 1 of our Newsletter, you reference what led you to create the youth voice framework Understanding the Continuum of Youth Involvement. You say that the Continuum can help educators avoid some of the common pitfalls in executing youth engagement initiatives. What are they? A: I think the reality is that when you look at the examples in the Continuum, you’ve got young people making a broad range of decisions, and implementing [projects] based on those decisions. There can be a couple of places where you can fall short: one is offering young people who’ve never practiced decision-making the opportunity to make decisions, and then expecting them to do it with 100% success—that’s one problem. And when the project is not successful, adults rescue the students so that the students don’t ever understand consequences, or feel accountability for their decision-making. They either aren’t allowed to fail at all or are allowed to fail in an unproductive, unsafe way. [If students are going to fail], it needs to be in a safe environment where they learn and understand not just the results related to accountability, but the nature of the decision-making that got them there. So it’s failure without learning, and that’s another pitfall that really pushes young people away. Failure with learning isn’t really failure. It’s learning. Q: What constitutes a safe environment for students? A: It’s about trusting that somebody has your back, that somebody shares your interests, and trusting that somebody can tell you the truth in a way that’s respectful and is about learning, and shared goals. It’s all of those things that you’d expect in any trusting relationship—whether that’s within a family, in a community, the workplace, or if it’s a teenager in a school. Q: Is there a temptation for an instructor to jump to the “Engagement” column of the Continuum and try to start there instead of building up to that achievement? A: The way that I use the Continuum--and the reason I created it—was to say “be honest about where you are and start there.” The Continuum is not designed as a hierarchy: it’s a strategic growth map on how to get to engagement. Because if young people have previously only been participants, they’re not ready to be engaged fully; you don’t have a relationship there to engage them successfully and effectively. [Young people] haven’t developed the tools, practices, or understanding of “cause and effect” with decisions, accountability, results, work and rework, and all of the things that go into being engaged. You aren’t ready and they aren’t ready Q: What do teachers and students need to keep in mind when venturing into a youth engagement initiative? A: It would be a stretch to take someone who was, say, a successful assembly line employee, and suddenly make them CEO of the company and tell them to “go do it and bring everybody else along.” It doesn’t mean that an assembly line person couldn’t become CEO, but you don’t make that jump without some investment, practice, and learning over time because the skill sets are different—even though the context is theoretically the same. How you engage in the classroom requires a lot of different skill sets on the teacher’s part, but also on the student’s part, too. Youth engagement is not just a change in practice for the teacher, but a change in practice for the young person, as well. And that’s why on the Continuum, the emphasis on accountability is detailed for both teachers and students at every level of the work. Q: But a student can’t expect that engagement will be a component of every class they attend every day, can they? A: That’s the reason why youth engagement needs to be a core strategy in education. And that means that engagement isn’t something that happens in one classroom—it happens across the educational environment. And that’s one of the pitfalls to [youth engagement] efforts that have burned teachers— and principals and administrators—who have put their necks out to engage young people. [Youth engagement] has not been systemically understood as a strategy for educating young people. So, it hasn’t really been safe for adults or young people trying to make it happen. Q: If engagement is part of one class a student takes, and not part of another, couldn’t that cause a student to become further disengaged in courses that don’t embrace engagement? Doesn’t every instructor want to be the “cool teacher” who’s always able to engage their students? A: I’m glad you brought that up, because youth engagement is not about “cool.” That’s a misconception. It’s a fundamental misunderstanding of what engagement is, and it’s a conversation I’ve had many times with adults. Kids know which of their teachers are trying to be “cool,” and trying to be their friend—and those aren’t the ones they’re engaged with. With the kids I’ve worked with, I made sure they understood that I wasn’t their “friend,” [but their partner and supporter in whatever we were trying to accomplish.] I’m generally a friendly and easygoing person, but in this relationship, the engagement [with my students] was about a shared goal, discipline, and solid, trusting relationships—we were working together on something. I always told them I would work as hard for them as they were working for themselves. But, that as soon as I was working harder, we would have to stop and assess our relationship, focus, and work together. Students may like some of those “cool” teachers, but if they’re not teaching them, they know it, and they’ll call you on it. It’s really important to note that engagement isn’t about popularity, it’s about effectiveness. Students are smart and intuitive about this. Q: The teachers I remember from high school and college whom I learned the most from, they were all pretty serious about what they were teaching. A: Authenticity is absolutely at the core of it. If you think about who your really great teachers were, although some of them might have been cool, some of them were absolutely not cool. There is research out there that talks about how the nature of the teacher-student relationship guides and determines how effective that learning environment is, and what subjects kids end up being drawn to. And it’s not necessarily the subject, but how it’s being taught, and how you and the teacher engaged in that learning together. Q: You’ve pointed out in our conversations that there’s a difference between a “youth” and a “student.” A: We have this really bizarre structure where we call a 15 year old kid a “student” from 7:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m., and from 2:01 p.m. to 6:59 a.m. the next day, he’s a “youth.” The role of student and the role of youth are fundamentally different. They have different expectations. The adults they interact with behave differently, have different training, and provide different opportunities. And what adults do in the “youth” world and what they do in the “student” world typically don’t connect. So we create these multiple systems because it’s how we’ve approached things historically, rather than thinking about what does it mean as a city, for example, to provide good opportunities for youth to grow up here? Q: So these terms aren’t interchangeable? A: In no way, shape or form except that [you’re] referring to the same kid. Teachers don’t learn about youth development, youth development people don’t know what’s going on in classrooms, afterschool programs aren’t tied to what’s going on in schools, and [adults] in the classroom don’t know where kids are going afterschool. Q: Service-learning has become a popular way to engage students. Is that an effective way to introduce students to youth voice and engagement? A: It certainly can be. I’ve seen service-learning in a variety of forms: I’ve seen it where a box is checked and where the kids only participate and do what they are told, or, at other times, where the kids have only nominal voice, and still others where service-learning is transformative, where there is true engagement. Service-learning as a tactic for youth engagement can be really transformative—for student and teacher—with the right approach and philosophy behind it. The devil is in the implementation details. Q: Going back to a term you referred to earlier: how do you introduce students to the concept of accountability? A: If you watch young people interact with each other, there’s a whole lot of accountability [because] they’re approaching each other from an equal power position. There is a sense of mutual responsibility. It reminds me of a quote I read somewhere to the effect of “accountability is what is left when responsibility has been subtracted.” Students don’t have much responsibility in school. The structure of education leaves them only accountable to sit down, stay out of trouble, and [get good] test scores. They’re not responsible or being held accountable for offering ideas to improve the school, to help prevent bullying, for mentoring younger students in their school. They don’t see their role in creating a positive school climate or maintaining the cleanliness of the school. Without any real responsibility, they are merely held accountable for taking the test, making the grade, be a decent kid and stay out of trouble. If they don’t do those, then there may be consequences. Q: You often hear students complain that they’re never going to “need” a certain course or area of study because it will have no bearing on what they want to do in life after high school. Why is youth engagement important in a longer view? A: Youth voice and engagement is about relationships, about learning how to navigate institutions, and learning how to communicate with adults, now and as young people move forward in their education or even careers. How do you ask good questions? How do you deal with uncertainty? Ambiguity? How do you have the confidence to connect with others when you’re on a strange campus that you’ve never been to before? How do you make decisions? All of these things have to do with how engaged you are in school, and in life before you get to college, for example. There are kids who are returning home from college because they’ve never been in an uncertain situation, or in a place where adults weren’t controlling the environment. They’ve never been in a place where they’ve had to make decisions that can have a significant impact on their education. And so they get to college and have to figure out what courses to take, they have to figure out their financial aid, where their dorm room is, and meet the person they’re going to be living with. They haven’t done any of that and it’s incredibly scary, and they don’t have the tools. Q: There’s a lot of discussion of issues like Common Core at all levels of government. Do you think that youth engagement as a core value of education will ever get that kind of attention? A: I don’t see anything yet in any of the discourse I’m aware of that indicates a shift toward the development of young people as a focus in education. If you look at what the dialogue is, and what the debate is about in this country, it’s about twists and turns in the institution of education, it’s not about learning, and keeping up with all that we know and continue to learn from science about how learning happens. We’ve built this superstructure that is the education system, and we’re creating all kinds of pedagogical debates and philosophies around Common Core issues, while remaining beholden to the same old structures and systems. There are all these conversations and policies trying to shift the rules in a system that has never decided that its goal for improving is actually to engage our students better in learning. Q: You’ve put forth some ideas and concepts about education that people might not be comfortable with. Some of your ideas could even be called subversive. A: (laughing) Well, they are. They are! They’re “subversive” because we’re really comfortable in education in running the Institution of Education—we’re not really comfortable in engaging students. It’s the context of a navel-gazing approach where we keep looking and tweaking The Institution as it exists, and iterating off The Institution as it exists without ever coming back and asking the fundamental questions about our relationship to young people and our goals [for them]. It is subversive because everybody is sitting comfortably in institutions of education and school districts that have failed chronically—particularly in urban areas—for generations, and a bureaucracy that keeps them from fundamentally having to change their approach. Q: What do you see for the future of education and our students? A: I think that the monolithic “one size fits all” school district is a model that is a thing of the past. Some are going to dismantle more slowly than others, and for a range of reasons including a lack of faith in government, and shifts in politics more broadly. I think that the centralized source of knowledge and expertise is no longer a part of our sociopolitical and cultural belief systems. If charters [charter schools], for example, are managed and learned from appropriately, and are they are successful, there are opportunities for more input and more learning than there is with one central gatekeeper and system. If you’ve got 10 charters in your district and a central office [then] you get to learn from perhaps 11 different, nuanced approaches to education, rather than one. To me, that’s how we can do better. But, districts and charters don’t often have that kind of relationship unfortunately. Charters aren’t a panacea. They are an opportunity to learn. I’m hopeful we can learn. Some of the best charters in our district [Metro Nashville Public Schools] are criticized for being “overly disciplinarian,” and for having an almost military type structure. But, the thing is that kids don’t innately dislike that. If they trust you, and you share a goal, and [this structure] is about achieving that goal, and they understand it, then they don’t resist that kind of thing. What kids resist is “command and control,” from people they don’t trust force-feeding them an idea they haven’t bought into, and don’t have a shared interest in. Once you’ve built a shared interest and a relationship of understanding, kids will engage when they understand that it’s part of getting them where they want to go.  It’s extremely complex. And, for me, understanding this distinction is fundamental to our ability to innovate and create education systems that actually work for students and families. It also suggests we are structurally and philosophically misaligned when it comes to much of our teacher training, classroom management, and policymaking. Complicated is a descriptor of industrial age systems. The concept is built around a system-first perspective. Systems define people (think assembly line). Complicated systems have many moving parts, but are largely predictable, centralized, and codified. Because of this, the past largely predicts the future. Complex describes dynamic and adaptive systems. The concept is built on a relationship-first perspective. People define systems, which means systems are alive and constantly changing. The past doesn’t necessarily predict the future and the outlier often has an outsized impact (think how one disruptive student impacts an entire class). Complex systems are frequently perceived as chaotic. “Three properties determine the complexity of an environment. The first, multiplicity, refers to the number of potentially interacting elements. The second, interdependence, relates to how connected those elements are. The third, diversity, has to do with the degree of their heterogeneity. The greater the multiplicity, interdependence, and diversity, the greater the complexity.” [1] In light of these properties, the abilities, lives, learning styles, and personal experiences of our young people and our families are infinitely complex. Layer those with the complex network of teachers, principals, administrators, and policymakers and I think the point is pretty clear. Education is complex. And yet, we force-fit this complex human network into a highly structured and increasingly complicated, but still largely top-down, education system. We distinguish this type of school from that. This new pedagogy from the old. These types of students from those. The adults who support social/emotional wellbeing from those who do other things. In-school lives as students from out-of-school lives as youth. The school bus from the school hallway. Teachers from learners. You get the point. But, it’s our young people who are forced to traverse this complexity even as we attempt to manage it as if it were complicated. Our leadership and management models don’t match their realities. And, changing this is going to require deep commitment and time, but is an absolute necessity for an already changed world. I suggest reading General Stanley McChrystal’s book Team of Teams to understand how he helped overhaul the entire premise and structure of national defense in response to the complexity of 21st century threats. Nothing on the planet was more complicated than the 20th century military industrial complex. But, for him, for the United States, changing from a complicated to a complex orientation was an existential imperative. Perhaps when we own the same sense of urgency about education, we will have the courage to move beyond complicated systems designed for adults in order to do what’s right for the complex lives of our students. It won’t be easy. Most adults won’t like it. But, designing more complex education systems is the only way forward. [1] “Learning to Live with Complexity” Harvard Business Review. September 2011. https://hbr.org/2011/09/learning-to-live-with-complexity  Well, now that I have your attention, there’s a good chance you are continuing to read to confirm your established “down-with-charters” position, or alternately, you are a “charter” advocate with your defenses up ready to blast me in the comments section. But, there is a reason I put “charters” in quotations. So, if you are an ideologue and obsessed with that word, either for or against it, or if you have established your “position on the issue,” this blog is especially for you. I am calling for a moratorium on the word itself: no more “charters”. Stop saying the c-word! It is a word about adults. It is a word about adult-led systems. It is a word about ideology. It is a word about politics. It has nothing to do with kids or families or communities anymore. This is a challenge to the School Board, educational leaders, policymakers, advocates, funders, unions, teachers, families, and everyone else. Let’s talk about kids. Let’s talk about communities. Let’s talk about the quality and direction of education reform by talking about student outcomes, about parent choice and engagement, about diverse opportunities to meet diverse student skills, interests, and family needs. Let’s hire a director of schools who wants to talk about these issues in their complexity and messiness, who won’t bite at the attempt to simplify things for the sake of politics and punditry. Let’s hope we have a new Mayor who will do the same. As a city, if we can’t engage in educational discourse without this word, then we aren’t having the right discourse, and we probably aren’t getting anywhere with it. If we can’t take this challenge then maybe the conversation is really about us and defending our position and fueling our righteous indignation. We thrive on the high emotions and the intensity of the debate and simultaneously over-simplify education reform to the point of meaninglessness. There are kids across the county in public school classrooms, in a variety of public school designs, with a range of curricula and a diversity of teachers and pedagogies, from diverse communities and families, with differing needs, aspirations, and expectations for their education. We need an education system that supports success for every one of them. We won’t get there with a binary debate or singular strategy. So, let’s take the challenge. Let’s drop the c-word and start a meaningful conversation about education in our city. by Teri Dary, Anderson Williams, and Terry Pickeral, Special Olympics Project UNIFY Consultants

In our last blog, we focused on what creative tension means in the context of relationships between young people and adults in our schools. We outlined core principles and assumptions that are critical for this work, and discussed how the roles for young people and adults shift in the creative tension model. This blog presents a series of real-world examples that demonstrate the use of a creative tension in carrying out intergenerational work within the school context. There are a few key ideas to keep an eye on. First, each example shows youth and adults working toward shared goals, with young people being viewed as meaningful contributors and partners in the process. Second, supporting their shared goals, you will see how personal goals and aspirations align with and support their collective work. Finally, each values the other’s experiences, perceptions, skills, beliefs, and ideas and understands that they are critical to achieving personal and shared goals. Ultimately, these examples are intended to demonstrate the varying ways schools and systems can support and nurture collaboration and shared outcomes between youth and adults. Curriculum and Instructional Design A high school chemistry teacher created a more connected learning process by organizing unit information on his white board by the content standards, and then highlighting for the students where each of these standards were addressed in labs, quizzes, class activities, homework, and tests. Rather than simply posting the standards, this is an active, dynamic process to help students understand how each discreet learning element ties to the bigger picture and connects to other learning. These connections then play out in quizzes, homework, and summative labs, which guide students in determining their level of understanding and focuses on demonstrating mastery rather than just obtaining a grade and moving on. Students are making decisions about how and when to study based on this knowledge and are better prepared to guide their own learning. Alternately, the teacher continuously engages students in the process of learning from design to assessment, helping them better understand how everything fits together and their role in both teaching and learning. A core component of the structure for this chemistry class is having students work in groups that stay the same throughout each unit. Groups are encouraged to apply critical thinking in labs and class assignments by altering variables and designing their own labs to produce desired results. In ensuring all students are contributing team members, everyone in the group is responsible for teaching as well as learning from others in the process. The result? Creative tension between the students and teacher in working toward shared goals has substantially increased learning, engagement, and ownership of the teaching and learning process by both the teacher and students. Basic Lesson Planning We were reading “A More Beautiful Question” by Warren Berger recently and he shared an example of a teacher who recognized the challenge of engaging students when teachers ask all the questions (and hold all the answers). He wanted students to ask the questions in class, so they would own the process of finding the answer. So, for one lesson, instead of asking “how long will it take to fill that bucket with water” and having the students complete a worksheet with prompts and places for calculations and so forth, the teacher took a video, a long video, of water dripping into a bucket and showed it to his students. It was mundane and redundant and monotonous and felt weird, like nothing was happening. Finally, almost exasperated, the students asked for themselves: “how long is it going to take to fill that bucket!?” Now that the students had asked, they also actually were intrigued and interested in finding out. As a result, the students built their solution not only from their own question, but from the shared experience of watching that water drip into the bucket. They wanted an answer, so they worked to find it. Parent Engagement One high school we worked with, like many around the country, was experiencing significant demographic shifts with a huge influx of students and families from Latin America. They knew many of their parents did not speak English, but also knew that they were sending home important information about the school, about their students, and so forth that the parents could not read. For starters, they knew they needed to translate their materials into Spanish. They contacted a nearby university and through their Multicultural Center found college students eager to assist. However, the university students requested that high school students in Spanish classes also be engaged in translating the various communications to parents. As a result, the school, Spanish teachers, high school students, and college students all worked together, sharing and enhancing each others’ skills and awareness of the issue. To do so required some changes in process for each and required creative tension among all to make it successful. Ultimately, the university students working with a countywide nonprofit established English classes for Latino families. School Governance A high school leadership class was designed to provide students an opportunity to learn and practice valuable leadership skills by addressing issues in their school and community. One group of students in the class decided they were concerned about students’ ability to transition from the overly structured high school environment to the unstructured college environment. They had never experienced or practiced the decision-making that comes with such freedom. To address this issue, they decided seniors should be able to have open campus lunch, to practice some additional independence. The group worked with their teacher to review board policy and school rules, surveyed local businesses, and developed an open campus proposal. (This process in and of itself was also an exercise in independence.) The principal gave permission to work on the project and provided a set of criteria that would need to be met. Additional provisions were made to address concerns raised by teachers, community members, and local businesses. Based on this work, the students developed a district policy and succeeded in getting the policy passed by the school board, allowing seniors to leave campus during lunch. Working across systems is inherent to working intergenerationally and requires the ability to generate creative tension rather than destructive. Complaints or protests or otherwise by the students could have just as easily shut down the opportunity and the solution they sought. Working together allowed it to come to fruition. Additionally, this process and the additional trust and responsibility provided to seniors generated improvements in school climate more broadly. School Leadership A group of high school students working with a community based organization began to research and ask questions about why only a handful of students at their school went to college each year, when they knew the numbers were vastly greater at other public schools across town. When they first raised the subject with their principal, she was immediately defensive and tried to shut down any avenues for continued research and organizing. In response, the youth requested a series of meetings with her to discuss the issue, their research, and their concerns; just with her, no pressure and no real need to be defensive in front of teachers, colleagues, etc. Ultimately, the principal became the schools’ biggest advocate for college access and, working with her students and her counseling staff, doubled the number of students who made it to college in one year. Their work together was highlighted in a documentary called “College on the Brain.” With their initial questions, the students had accidentally created a destructive tension scenario, because the principal did not feel safe to have the discussion without going on the defensive. Reaching out and clarifying their desire to work together and articulating how improving college access could be a shared goal for students, counselors and the principal, the students moved toward creative tension and enabled a powerful example of intergenerational work. School Climate Students, parents and schools around the country have created and implemented R-Word campaigns to eradicate the derogatory use of the word “retard” in their schools. With the goal of making schools safer and more equitable for all students, an R-Word campaign sends a powerful message, but one that is only made powerful by the commitment of students, teachers, school leaders, and parents. In other words, it is a community effort. Typically, these campaigns begin as a conversation between students and teachers who then get commitment from school administrators. In developing a plan and a kickoff on Spread the Word to End the Word Day, the school community works together to create banners and posters, to get food, to get commitment signatures and so forth. As a result, schools that have gone through this process of working together and worked toward a more inclusive school environment have seen dramatic improvements in school climate and reduction in bullying. There are clearly many ways each school can begin to incorporate creative tension to enhance intergenerational work. And, they all begin with a shared goal among young people and adults around a creating an engaging teaching and learning environment where all students and adults have opportunities to contribute meaningfully. The key is to begin. Start from where you are, start small, and seek continuous improvement. In our February 18 blog, we clarified the distinction between creative tension and destructive tension as they relate to our relationships and our work in schools. And, our example was focused on the relationships among adults in a school.

In this blog, we focus on what creative tension means specifically for the relationship between young people and adults in our schools. For starters, we cannot develop real creative tension unless we change the way we see young people and their role in education. What would happen if we decided our students were our partners in education, rather than mere recipients of it? What if we believed they had something to teach us? To teach each other? What if our goals were shared goals and our accountability collective? What if education were intergenerational work? How would this change the relationships between students and adults in a school? Imagine a student and a teacher holding opposite ends of a rubber band. As each pulls away or comes closer, the tension in the band changes. It moves. It makes sound. It has energy. But, if one pulls too hard, the energy generates fear and uncertainty in the other (What happens if she lets go? I’m gonna get popped!). Movement becomes limited. The energy becomes bound. The band is taut. It is not productive. This is destructive tension. Now, what happens if one relaxes the tension on his end? The band goes limp. It has no energy, no sound, no movement. It sags. What does this mean for the one left holding it? What about the one who let go? This lack of shared tension (energy) results in destructive tension. In creative tension, the energy each person contributes is dynamic and dependent upon each individual's personal goals, their collective goals, their relationship and their trust in each other. It is constantly changing. So, to remain productive, we have to constantly communicate the tension we need and listen to others as they do the same. Our relationships then must become more dynamic and multifaceted such that the right tension becomes both intentional and intuitive. So, what does intergenerational work mean? Intergenerational work is neither about young people nor adults. Intergenerational work is about the work. It is a change strategy that believes that different generations bring critical experiences, perspectives, skills, and relationships to the work that the others do not. And, to effectively achieve our goals, to do our work, we need all of us working together. Perhaps the most established model of intergenerational organizing comes from Southern Echo in Mississippi. While their community organizing model does not directly translate to schools, its descriptions of what intergenerational means are informative. According to Southern Echo, intergenerational means: 1. Bringing younger and older people together in the work on the same basis. This principle is simply about building a collaborative approach to the way our schools function. It is as true for intergenerational relationships as it is for relationships between adults. Maybe that's why we struggle with “motivating” students. Rather than imposing our goals and ways of functioning on students, we should engage students with us, not simply try to convince them to do what we want them to do in the ways we want them to do it (on our basis). There is no creative tension in that approach. Our schools could follow a wise mantra often repeated by the youth leaders of Project UNIFY: “Nothing about us without us.” In this, there is creative tension. 2. Enabling younger and older people to develop the skills and tools of organizing work and leadership development, side by side, so that in the process they can learn to work together, learn to respect each other, and overcome the fear and suspicion of each that is deeply rooted in the culture. This principle means that each young person and adult has the opportunity and obligation to bring his skills and develop his weaknesses for the betterment of the collective. The right tension depends then on the positive and negative expectations one has for self and others. For example, a student may have higher expectations for himself (+) and but has a teacher with lower (-), leading to a (+-) relationship. This dynamic happens just as readily in the opposite direction as well. As a result, energy and strategies for skill development and creation of goals are misaligned and destructive tension rules. Maintaining creative tension in intergenerational work means nurturing collaborative partnerships that build upon inequitable skills, with youth and adults both learning from and teaching each other. The roots of this dynamic between youth and adults, however, are deeply rooted in our culture, so addressing them effectively is indeed counter-culture and demands fidelity and consistency, and a touch of a counter-cultural spirit. 3. It is often necessary to create a learning process and a work strategy that ensure younger people develop the capacity to do the work without being intimidated, overrun or outright controlled by the older people in the group. “Control” and “exercise of authority” are great temptations for older people, even for those who have long been in the struggle and strongly believe in the intergenerational model. Culturally, young people are taught to defer power to adults and adults are typically rewarded personally and professionally for acquiring power. It is deeply rooted in our education systems and our economy. So, breaking out of that dynamic does not happen quickly or easily. Having a shared intergenerational model and shared understanding of and commitment to the resulting creative tension is critical for the work to take root. It cannot be ad hoc. Young people and adults both need to own it, respect it, celebrate it, and call on it when they feel that it is not being executed with fidelity. There are some important assumptions that are inherent to this work:

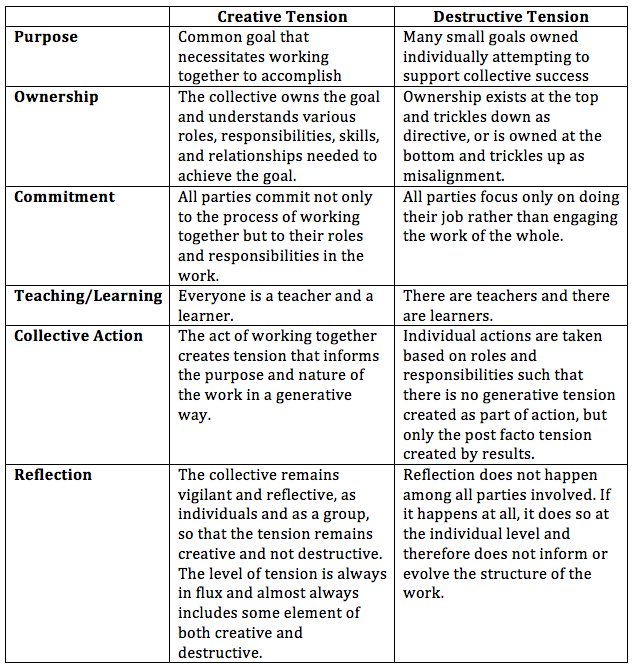

In our next blog we will focus on a couple of case studies where creative tension and effective intergenerational work have improved school climate and outcomes. Written by: Anderson Williams, Teri Dary, and Terry Pickeral originally published by the Learning First Alliance The problem with public education is that there isn’t enough tension. The other problem with public education is that there’s too much tension. And, perhaps the biggest problem is that both of these are correct; and we don’t distinguish between creative tension and destructive tension. Without distinguishing between the two, we cannot intentionally build structures and relationships that create the systems our students need: systems of shared leadership, strategic risk-taking, and mutual responsibility. Systems of creative tension. Instead, we more commonly build top-down structures that generate destructive tension and bottom-up structures to avoid, relieve, or push back against them. At all levels and relationships, public education is replete with destructive tension. Whether it’s the policymaker focusing on test scores he has no control over, the School Board trying to improve classroom practice it has no experience with, or the district administrator trying to empower principals who have systematically been disempowered, we lack the structures and processes to support creative tension. So, our tension becomes destructive, structural stress, which becomes a self-fulfilling and redundant system of production. So, what are the key differences between a structure that produces destructive tension and one that generates creative tension? The following shows two possibilities for some relatively simply planning among school faculty to improve student outcomes. While this just illustrates the start of planning, the same models and considerations can be extended through all stages of action, reflection, assessment, and improvement.

Making a Plan: The Destructive Tension Approach A principal is approached by a group of teachers who are concerned about increased expectations to provide interventions and supports for students with intellectual disabilities, but without any additional planning time for new strategies. The principal listened to their concerns and then explained the rationale he used when making this decision. He assured them it was the right decision for their school. The principal recommended that the teachers use their current individual prep time to collaborate with other staff and develop individualized plans to meet students' needs. He asked to see their plans at the next staff meeting. Making a Plan: The Creative Tension Approach A principal is approached by a group of teachers who are concerned about increased expectations to provide interventions and supports for students with intellectual disabilities without additional time to develop and plan for the new strategies. The principal adds this topic to the agenda of a staff meeting scheduled for the next week. In that meeting, he asks staff to consider what each is doing in their classroom to ensure all learners have equitable access to instruction in meeting their individual needs. (Reflection) Through the discussion, the staff begins to recognize that too many learners are not finding success and that staff as a whole uses a fairly narrow range of interventions. (Ownership) Together with the principal, they agree on a shared goal to adopt a wider variety of interventions and supports to increase student success and identify the ones they want to focus on first. (Purpose) As part of this, they make a plan to have fellow teachers who are experts in the priority areas provide brief peer-to-peer professional development opportunities during each staff meeting. Over time, they aspire to have each teacher share their successes and challenges with the group. (Commitment, Teaching/Learning) The principal and staff develop a plan to allocate time for teachers to plan for implementation and engage a teacher coach to provide modeling and time to practice and refine their skills. (Collective Action) The principal and staff schedule regular, frequent opportunities to reflect and refine practice individually, with the coach, and in professional learning communities. (Reflection) To reduce the destructive tension that often undercuts efforts to improve how our schools function, intentional practices that nurture creative tension need to be imbedded throughout the relationships within the school and across a school system. Note: These relationships include not only adults, but also the young people as the largest stakeholder in public education. In their absence as a constituent in the variables of the creative tension model, we will never build structurally creative systems. Keep an eye out for our next blog to focus on creative tension among young people and adults. Written by: Anderson Williams, Teri Dary, and Terry Pickeral originally published by the Learning First Alliance |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed