|

A couple of years ago, I was working with a multi-billion dollar, global financial services company that had (pre-Covid) a vast network of on-location staff as well as remote online and call center staff to provide direct support to their customers. As we talked about growth and change in their company and their market, we explored if and how they were, or could be, learning from these front-line employees spread across the globe. What were these people hearing directly from customers that the company really needed to hear and understand?

We’ve all heard the saying about the importance of having “an ear to the ground” so we can sense imminent changes in our work environments and markets, but how well do we do it? Who has their ears to the ground more than those meeting our customers where they are? Dealing with their problems? Frustrations? Who has the potential to positively or negatively impact our customers minute-to-minute on a daily basis? Too many of the people on the front-lines of our work think they are too “low on the totem pole” to speak up in our companies or don’t have the power to create change in their own work. And, too many companies think the same way. As a result, many of us are really missing the opportunity to become more resilient, adaptable, and creative organizations. When we don’t listen to our customers and the employees who interact directly with them, we run the risk of missing indicators of emergent change in our markets, products, and even broader society that can lead our products and companies toward their next iteration. Through a simple, facilitated reflection process, this company - which thought it did a good job listening to its people because they could reel off some good anecdotes - realized that their listening to front-line employees across the organization was far spottier than they would like. They recognized that their anecdotes were about specific leaders or departments that carried this value of active listening rather than a reflection of a systemic approach or strategy by the firm. The implications from this kind of company self-awareness became pretty vast as they then considered who they needed to train, how they needed to adjust professional roles and expectations, and how a better process of listening could improve their product offerings. To cultivate a powerful culture, people at all levels of our companies need formal and informal outlets to provide feedback, ask questions, and share ideas and solutions. This is just strategically smart. It’s not about being nice to our employees. Not only will listening to our employees make our company more resilient and adaptive, it will also make for happier employees and better products and services for our customers. When they know their ideas and insights are respected (even if not always acted upon), our people will more actively and critically identify customer patterns and frequent issues that we may never see, and solve them in ways we may never have thought of. They will own their work and the whole company will perform better because of it. Powerful cultures don’t happen by accident. They result from powerful leaders, powerful relationships, and organizations that understand and leverage the power of their people at all levels. Also relevant: “Does your organization have a powerful culture or a culture of power?”

0 Comments

I wrapped up 2019 with a reflection on advice, and unwittingly found myself again reflecting on the topic as 2020 thankfully comes to a close. There must be something about this time of year! Anyway, here are a few more thoughts on advice from 2020: 1. If a person starts with his advisement and not by listening to you, run. Run fast. He probably believes he is a great advisor or mentor because he knows so much and has so much to say. But, the great advisors and mentors are the best listeners and thinkers and question askers. It’s not what they know so much as how well they surface knowledge with you and within you. Advice should be arrived at collaboratively. 2. Listen to all advice in the context of that person’s experience. Advice is rarely directly transferable. You have to peel some layers back to get to the nugget unless that person has experienced the exact problem in the exact industry with the exact people and the exact business model as you. Clearly, you don’t dismiss them because of this discrepancy, otherwise you’d never find yourself a good advisor or mentor. But, you need to know where they are coming from to understand what they are saying - and, of course, understand where you are to know what to do with it. Advice is an act of translation. 3. You have no idea what you are doing, but you know what you are doing. This is a seemingly odd contradiction, but boils down to an obvious translation: you know some things, and you don’t know some things. Good advisors or mentors will never make you feel stupid for what you don’t know, nor will they ever let you feel like you have it all figured about because of what you do know. Their advice should uncover both, and leave you encouraged and humbled, motivated and uncertain. Advice should generate a sense of creative tension. 4. Gather all of the advice you can and throw away as much as you should. Advice is for learning and improvement along your journey. You are not, and should not be, beholden to it - although, you should be accountable nonetheless. So, if you take advice, you should know and be able to communicate exactly why you took it. If you don’t take advice, you should know and be able to communicate exactly why you didn’t. If you can explain and communicate the result in this way then you can show that you’ve listened and learned and gotten clarity out of whatever advice you have received - accepted or denied. A good advisor doesn’t expect you to take them at their word, but they should expect you to demonstrate that you listened, translated, and acted accordingly. Advice is a prompt, not a directive.  My commitment to creating has presented me with many media over the years - some art, some not - each of which has its own tools, challenges, and creative outcomes and brings its own unique joy and value to the world. Drawing. Painting. Printmaking. Sculpture. Digital media. Community organizing. Advocacy. Nonprofit management. Educational consulting. Entrepreneurship. Life itself. Several years ago, I even wrote a book about it. Last night, for the first time, my medium was flowers. Thanks to a company called Poppy, I had a box of fresh-cut, direct-from-the-farmer flowers delivered to my door to create with as I saw fit. I had big aspirations of enjoying the process with my two daughters (6 and 8), but the day kind of slipped away from us. So, as they wound down their somewhat hectic day, I actually had some time alone, some me-time, some "studio time" with this big, bunch of color, height, form, movement, rhythm, and rhyme in the medium of Poppy flowers. Part sculpture, part painting, part meditation - my first experience with flowers-as-medium was a treasured and peaceful and unexpected end to my day. And, this morning, the results met me at breakfast - presenting me again not only with the joy of the diverse beauty, color, form, and pure nature of the flowers - but also a moment of reflection and self-critique, seeing things in the new light of a new day, showing me how I could have done a better job arranging them. This is the creative journey that drives life - no matter your medium. Creating matters. Thanks, Poppy. I’ve already learned a lot halfway through Techstars, but the clearest and most obvious is: if you want to test your startup, go have a 100 conversations about it. I don’t mean that abstractly. I mean 100 actual, focused conversations.

Go give your pitch 100 times and see if people get it. See what questions they ask. See what questions you start to ask yourself - as you stop focusing on crafting what you are saying so much that you can actually listen to yourself, and listen to them. Describe your product to someone who knows nothing about it. Describe it to someone who knows everything about it. Describe it to someone who is a user, knows a user, can’t imagine what it could possibly be used for. Describe your product 100 times. Describe your market to these same people. Describe your go-to-market. Describe all the things you know about how you are going to be successful 100 times and see at what conversation number you realize you actually don’t know that much. If you don’t get to that point, then there’s a good chance you are still talking more than you are listening. You may need more than 100 conversations. Describe your end user 100 times. See if you can describe the actual pain point that you solve for them. See if you can define why you are a must-have and not just a nice-to-have. See if you can convince others, or yourself, that someone will actually change their behavior to adopt your product. See how many times it takes before you don’t really even believe yourself anymore. At that point, you’re a lot closer to success. These 100 people aren’t “right”. In fact, they will contradict each other a lot. They will make the already difficult process of starting a company temporarily seem that much more difficult. So, why in the world would you do this to yourself? Because you’re not right either. And, the repetitions and iterations and brute force that talking to 100 people generates are your best start to getting there. M.C. Escher: Metamorphoses Image: https://images.app.goo.gl/nSMsrkBFAoniDFsF9 This is a hard lesson learned in the land of early startups and new products, but there are good reasons that it’s both a hard lesson and one that founders keep having to learn for themselves.

Entrepreneurs are typically driven by a vision, one that they hold dear, perhaps for many years, of how they can and will solve a pain that they’ve experienced and that they believe a lot of others experience - and will pay to fix. That vision is powerful. It wakes the entrepreneur up every morning. It inspires those first people willing to have coffee with you to bounce your idea off of. They validate it, making the vision that much more powerful. It excites friends and family who feel your passion and may even be willing to invest in it. They believe, which adds more fuel. It draws those first people who want to join your team and help build your vision. They want in. That vision is fundamental. It’s foundational. So, it’s hard to accept when in the face of business reality the vision loses its potency and immediacy. The vision is still important and deeply rooted, but it becomes increasingly marginal in the face of here-and-now questions about adoption, what you’ve learned from the market, and how you have used or will use investment to turn the early product into a viable business. In other words, unless and until people are using your product (people who aren’t your coffee-going friends or family) and you are building and iterating based on that feedback, your vision is in a state of diminishing value to your business. I’ve stumped even seasoned founders - after hearing their thoughtful and thorough business strategies, clear visions for the necessary features and functionalities of their products, and go-to-market plans showing how users will be downloading their app by the thousands - with a simple question (scaled to the business/conversation): Who are your first 10 (or 20 or 100) users? Followed by: why will they use it and why will they keep using it? And then, why will they tell someone about it? It seems obvious after I ask the question that you can’t get to 1000 users, much less 100,000, if you can’t get, and keep, your first 10. If you’re doing it right, the product will evolve rapidly as those numbers grow, so it’s ok to think about a small but as-representative-as-you-know first set of users who you want and need to learn from to prove your value. In fact, you must. One critical part of securing those early users is articulating the value you are going to deliver and then delivering it. It’s not necessarily about the magnitude of value for an early adopter. It’s about trust and belief that you and your product can deliver what you say you are going to deliver. Unfortunately, founders often fall into a self-created chasm between their vision and what they have had the time and investment to deliver successfully as a working product to date. Imagine a circle on a white board - let’s say 4 feet in diameter. This is the founder’s vision. Now, imagine a circle inside that circle that is say 6 inches in diameter. If you promise the big circle and deliver the small one, you’ve lost. It’s a major disappointment to the people who thought they were getting the big circle. You’ve not just over-promised and under-delivered; you’ve breached some level of trust. You’ve created even more doubters. Alternately, if you promise the little circle and deliver it, you win - even if it’s with a smaller user base and only delivering on a fraction of your vision. They may not yet be blown away, but they are that much closer to lining up behind your vision. In either scenario, you’ve delivered the exact same (small circle) value with dramatically different outcomes for your business. It’s important to understand that this value scoping is not compromising your vision. In fact, it’s the opposite. It’s building the product and the users and the business that are required to achieve the vision, which always takes longer and requires more money than you think. As good as it may feel and as validating as it may seem for your early product, confirmation that the market has a problem and that your product seems like a good solution should not be confused with finding product/market fit.

Particularly in a B2B context and especially at the enterprise level, new product sales and adoption encounter a world of organizational dynamics, dysfunctions, disparate priorities, funding streams, and basic inertia that often are what actually create the need for your product but also undercut demand. My first startup created a mobile communication tool for both the education and the healthcare sectors at different times. In both, there was a clear and acknowledged communication problem - in education among schools and students, and in healthcare among administration and physicians. In each sector, we found a solid early interest in our solution. Both sectors, however, are also highly regulated and compliance driven. Both sectors are risk averse and bureaucratic. Both sectors have complex decision-making structures and resource allocation processes. And, both sectors are notorious for culture problems among administration, front-line staff, and the people they actually serve. This is why both sectors have severe communication problems (need), and also why both sectors have not been able to commit to solving (demand) their communication problems. Needing a communication solution and demanding one are two different things. Our startup got a lot of head nodding and early interest and affirmation, but was never able to scale our sales to match. In hindsight, we had achieved problem/solution fit (need oriented), but a couple of years later we were still searching for product/market fit (demand oriented). Image: https://forum.brickset.com/discussion/21293/requesting-information-regarding-2-top-vs-top-fit-together-1x1-round-bricks%EF%BB%BF How to understand the advice we get as entrepreneurs (and what to do with it) is perhaps the most important topic that 2019 has left me wrestling with. There’s so much more to be written and explored, but I wanted to get something down to help organize my thoughts before 2020 is fully upon us.

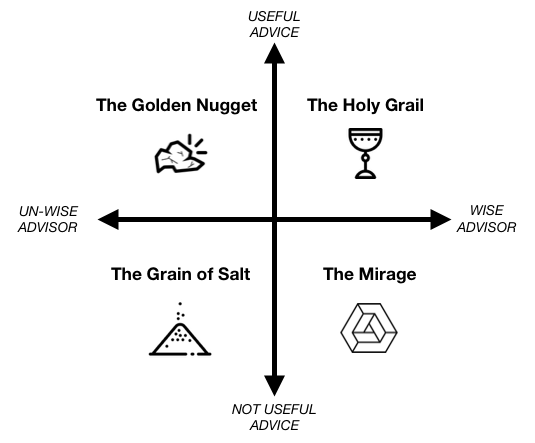

Here’s the confusing reality: Wise advisors can give wise advice, but wise advisors can also give un-wise advice. Un-wise advisors can give un-wise advice, but un-wise advisors can also give wise advice. So, what are we as entrepreneurs supposed to do with this? For starters, we need to sort advice and advisors into impermanent buckets so that we can focus and be most efficient with our learning at a given time, for a given stage of our company, or around a particular challenge or opportunity. The quality of advice and advisor can change based on context, so these categories should be at least somewhat fluid. To be clear, however, some people will likely stay in their buckets permanently. Here are a few ways to think about sorting advice and advisors: The Holy Grail This advice is hard to come by. There just aren’t that many people in the world who have the wisdom (which fundamentally includes their own self awareness) required to give good advice. Additionally, there just aren’t that many people who can listen to and understand our problems dispassionately and with the ability to help us identify the structural patterns and problems at the root of our issues or opportunities. If you find this person, hold on to them. When you get advice from them, dissect it, explore it, come back to it, let it marinate - and, ultimately, make sure it’s not The Mirage. The Mirage This advice is easier to come by than I ever realized. And to be clear, in my experience, it’s rarely - if ever - malicious. In fact, it often comes from wise people with a genuine intention to help us. For this reason, The Mirage has all of the appearances of The Holy Grail. Determining the difference has everything to do with our own understanding of our business, our needs, our questions, concerns and so forth and our ability to think critically about advice in that context. The trick of The Mirage is one of convoluting the value of the messenger with the value of the message. The Golden Nugget This advice is the fundamental reason we must always listen for understanding and keep an open mind. It’s the reason we must remain hungry as a learner, no matter who we are talking with. Just as we can’t accept advice simply because of the person who offers it (The Mirage trap), we should not dismiss advice out of hand for the same reason. It is potentially the person who knows little about our business or our product who can offer an insight that breaks us out of being stuck or sheds light on our next move. They might not even realize that they are giving us advice. We just have to listen for and grab that Golden Nugget when it shows itself. The Grain of Salt Again, I’m not trying to be ugly here but just strategic in how we think about advice. This isn’t about individual people. Sometimes advice just isn’t relevant. Sometimes other people’s experiences, views of the world, or approaches to problem-solving just don’t match our own personally or in terms of our business. It’s OK. Just know that. Be nice. And, file this advice away somewhere. Still, I’d say to archive it, don’t delete it. Who knows, we might find in time that it ends up a Golden Nugget.  I generally try not to write about a topic that’s already been exhausted by countless other blogs, videos, talks, etc. but sometimes I get bold enough to think that I might add just one more re-frame that might, just maybe, help to simplify a topic that has been over-wrought, over-written, and most importantly over-thought. What I’ve found with product design - as with most things - is that it doesn’t matter how many tools you have at your disposal, how many blogs you’ve read, frameworks you follow, or videos you’ve watched. If you don’t have the foundational mindsets to apply them well, then what you build will check all the boxes and deliver little of the value. So, I’d like to strip the topic of human-centered design down to three basic mindsets - and then Google can tell you everything else you need to know about how to actually do it. Mindset #1: Be Human. You are a human being designing products for other human beings. (I warned you I would make it basic.) While this is a painfully obvious statement, it’s also often ignored in product design and is a chronic reason for product failure resulting from lack of adoption. I spent many years in education and in healthcare - both in technology and not. The number of products and services in those two industries that are designed to facilitate those two industries - not the people working in them or the outcomes they are supposed to achieve - is one great driver of their continuing bureaucracy and inefficiency. In education, we build tools and strategies for tracking student risk indicators but do little to design tools and processes to increase student engagement, mental health, or otherwise. In healthcare, we spent countless billions of dollars to manage and make sense of patient healthcare data but invest relatively little in helping people access healthy choices and manage their own health and wellness. So, what are we trying to accomplish and for whom? To remain human in our product design, we must:

Mindset #2: Be Humble. You don’t know everything and, if you work hard enough, you will probably find out that you don’t know very much at all. This is a good thing, not a weakness. In fact, after a dozen years in education and youth work and having co-founded a company building a software product based on that experience, I became a much better product designer when we pivoted the company to healthcare and I actually didn’t know anything at all. All of my experience and previous knowledge in education wrongly gave me the impression I had all the answers and made me less curious about what people thought their problems were - and less honest about what they would actually be willing to do to solve them. In healthcare, I knew it was learn-or-die for our product and our company, so I approached product design with more humility. To remain humble in our product design, we must:

Mindset #3: Be Hungry. If you aren’t deeply, personally motivated by the creative, iterative process of product design, you will not be able to sustain human-centered design over time. Getting feedback from our users is difficult, often humbling, and at times humiliating. It’s a learning process and learning requires a deep desire to face and learn from mistakes - and not cover them up. Getting feedback on an early product is particularly challenging as we often try to explain away its known deficiencies more than listen to the feedback on what’s there. Our insecurity takes over. As I mentioned above, humans (meaning us) are emotional, but we have to be bigger than our own egos if we are actually going to solve real problems for our customers. In other words, our hunger must be stronger than our ego. To remain hungry in our product design, we must:

Feature Frenzy and its close cousin Shiny Object Syndrome (S.O.S) are startup killers. They confuse product direction, muddle the sales pipeline, and frustrate developers and eventually our users - and then, as a result, all of us.

And yet, we want aspirational and aggressive product roadmaps so that we can excite the market with our product vision, demonstrate responsiveness to early customer feedback, and possibly share our vision and direction to seek investment to grow the company. Sharing a big vision, being creative, and coming up with exciting and dynamic solutions are why we became entrepreneurs after all! So, the challenge is real. Recently, I pulled together a workshop on how to avoid Feature Frenzy but maintain an aspirational product roadmap, and here are 10 tips to consider: Keep your aspirations focused on your business first, not your software. Software should enable your business. New features (i.e. more software) should have clear and direct business value. See if you can test the business value first without building more software. It’s amazing what you can figure out with some conversations, some data, and maybe a spreadsheet. If that won’t cut it, just make sure you are building the smallest amount of software possible to test the business value. Be clear about the purpose of your roadmap. There are lots of roads and lots of maps that serve lots of purposes. So, you just need to be clear at all times which one you are talking about and who it is for. The roadmap for your tech team and the roadmap for your investors or your customers are not the same in detail or message - even though they should align in direction. Never forget: Products are for customers, so your roadmap should take them somewhere. Entrepreneurs like new things and get excited by the next thing. But, the milestones on a product roadmap should be focused on delivering some tangible value or specific outcome to your user. Beware solutions looking for problems. Entrepreneurs are problem solvers, so we come up with solutions. New features can be dazzling for us and for our customers, but a pile of new features that seem like a solution to us doesn’t necessarily solve a customer problem as they understand it. A startup product roadmap should focus on finding answers to critical market hypotheses. Our early product development priorities and sequencing should lead to validating or invalidating the hypotheses that are core to early adoption. If it includes anything else, it’s probably noise for you, your team, and the client and will obfuscate the testing of the value proposition. It’s easy to come up with features customers love, but a lot harder to build a product they will actually use. Beware solutions to problems that are nice-to-solve but don’t need to be solved. Ideas and feedback from the market on what’s nice-to-solve often comes clearer and faster than the underlying what-needs-to-be-solved. We have to dig deeper into our customer problems than they are able to and come up with solutions they don’t have the time, inclination, or experience to create for themselves. Be aware that users who say email is their problem will often design email as their solution. I have lived this one many times trying to improve communication in schools and in hospitals. Don’t ask customers for solutions. You have to dig into their problems, listen for understanding, and solve from there. Beware the shiny object. When you see it, check your reflection in it before you grab it. Figure out why you think you need it. Just say no. We have to communicate that we are listening and care about our customer feedback even when we don’t take it. But feedback like: “If your product just did X, we’d be ready to buy” or “If you just added this button, we’d start onboarding all of our users” is almost never true. If we chase those things, we will almost certainly kill our product. Be honest about what you can deliver and when - and then deliver it. Overselling puts our product roadmap in chronic debt and is a sure path to disappointed customers, frustrated product managers, and uncreative developers. Selling something small but valuable and delivering it is a win. Selling something huge and then only delivering that same small-but-valuable element becomes a loss. As a bonus, I highly recommend watching this video: 20 Years of Product Management in 25 Minutes by Dave Wascha Image: https://wavelength.asana.com/work-plans-high-level-objectives-roadmap-week/ |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed