|

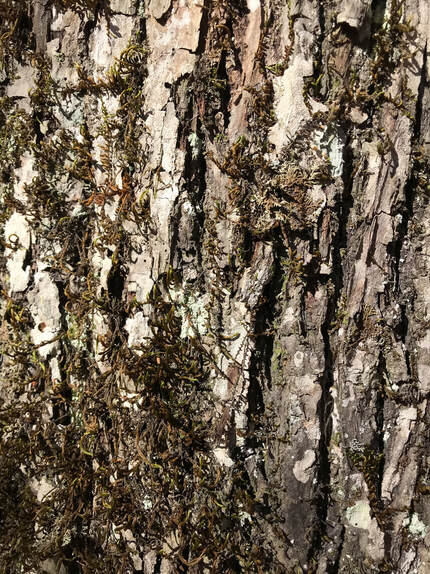

25 years ago, when I learned to paint and draw, the learning process had nothing to do with technique. In fact, by most people’s standards, it had little to do with painting and drawing at all – at least if I was doing it right. I was being taught to see. Once I could see, I could paint. And, while I don’t paint or draw at this point (someday again), I keep this lesson with me in every aspect of my life. To create, to find meaning, to communicate that meaning, I must be humble enough and patient enough and open enough and diligent enough to see myself and my world in its essence, to understand what it is offering and telling me – and then to create from there. I took a walk in the woods today, and everywhere I turned nature was asking me questions. It caught me off guard honestly. I just wanted to get out and get some exercise with the dog, but the woods wanted me to do more. They wanted me to see. To paint. A self-portrait. To be clear, I didn’t paint a thing – except in my mind. I tried to see what nature wanted me to see; myself, reflected in her. And, in her own constant changing with the wind and the water and the light and the seasons, she made it clear that my portrait was transient too. I am ever becoming a new self, seeing a new self, if I’m willing. So, here’s what she asked. 9 simple questions I should probably answer every day:  What color are you today? Color is a vibration. It is the perception of energy, wavelengths. So, what is yours today? Is it what you want it to be? How do others see it?  What colors do you surround yourself with? How do they blend or complement or contrast with your own? What frequencies do you absorb? What bounces off?  What’s your texture today? What coarseness is unavoidable at your age, given your life, experience? What strength can be created in the layers? What wisdom? What beauty?  What’s your light source? Where do you find your light? Do you run toward it? Look askance? Turn your back? The light is there and it’s bigger than you.  Where do you cast a shadow? How long is it? Is it getting bigger or smaller? Who is in it? What thrives in its cover? What fades or dies by it?  What’s your background? What past wraps you in stories without words? What blurs and fades? What defines your form? Your sense of shape?  How much space do you take up? Do you fill the empty space? How much positive space? How much negative? Are you the right size in your world, for your world?  What is in front of you? What lies beyond the canvas? What will you see in tomorrow’s portrait? And tomorrow’s tomorrow? Where you look determines what you will have the chance to see.  Do you accept the beauty? She didn’t ask where I find beauty or what I find beautiful. Its ever-presence was implied in her question. The question was whether and where and how I am willing to accept the gift.

4 Comments

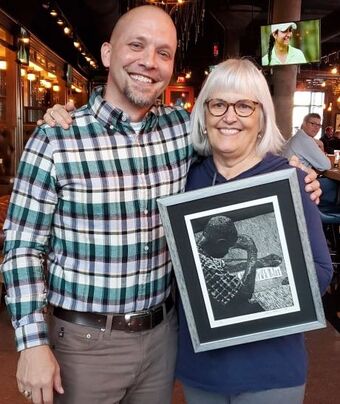

This is a curious 25+ year story of the first work of art I ever showed publicly and the first work I ever sold. In 1995, I made my first print, a linoleum print. I was a senior in high school. I made it from a black and white image of a black man, maybe a young man, in a plaid, short-sleeved shirt, who appeared to be taking a test of some sort, or reading a sheet of paper anyway, sitting at a desk. I won an award for that print at a statewide high school art show. The linoleum block and the print still hang in my house. It also became the first piece of art I ever sold. My teacher suggested $35 dollars because the woman who wanted to buy it worked for a nonprofit and that seemed a good price for the cause. It was a moment the details of which have never left me. It was a moment when art first started shifting from something I enjoyed to showing me something about who I am. Fast forward 7 years. I have finished college and an MFA and have returned home. I am having my first solo art exhibition of my career. It had nothing to do with education and didn’t include any linoleum prints. My sister had invited a woman named Jane who worked at a nonprofit organization called Oasis Center where my sister was on the Board. My sister thought the world of Jane. I had met her only briefly and hadn’t heard of Oasis Center. Jane came to my first solo art show. Fast forward 3 years. In addition to teaching art, I am now doing community organizing and education advocacy with a small nonprofit that works with marginalized youth in East Nashville – the tie to that first image and artwork is not lost on me. The organization I work for called Community IMPACT is becoming a part of Oasis Center – a larger youth-focused nonprofit that could support our work and our young people more holistically. I was having my first meeting with my new boss, Jane. I sat down in her office and looked at the sliver of wall to my right above the narrow table and there was a linoleum print of a black man, maybe a young man, in a plaid, short-sleeved shirt, who appears to be taking a test of some sort, or reading a sheet of paper anyway, sitting at a desk. Jane had bought my first work of art 10 years prior. I was shocked. She was shocked. Jane had finally met the artist, or at least made the connection. We both remembered the story. Fast forward 16 years. Jane is retiring from a life dedicated to creating opportunities for young people. My journey has been more meandering, but always rooted in what I learned in the arts, creating, communicating, connecting. I haven’t seen Jane in years except occasionally in passing somewhere along Shelby Bottoms Greenway. Out of the blue, I get an email from a former colleague who still works with Jane. It turns out that in an office move somewhere over the years, Jane had lost contact with my print. They had recently been surprised to find it in the art studio at Oasis and Jane had shared this story with her. Jane was apparently moved in seeing it again, which, of course, moved me in reading about it. So, here we are 26 years later. My print is being cleaned up and reframed to be given back to Jane to celebrate her work and retirement - reminding me that I am an artist and that the things we create have lives and journeys and meaning far beyond us. So, today, I am writing in celebration of Jane’s journey, her gifts to the world, the possibilities and stories she has helped create, their interweaving with my own, and acknowledging a simple linoleum print that has been a curiously common thread between us for almost three decades. Congratulations, Jane. Thanks for all you have created. Much love. Always. Anderson Williams (Class of 1995) 14 years ago on April 27, 2006, my Father committed suicide. He had no light inside. Living with suicide for all of these years, I am ever aware that I have never had to fight that darkness - that Depression that ultimately consumed him, killed him. Largely thanks to my Mother’s tireless effort, indefatigable will, and a light that is implicit in her being, my Dad left me a light inside that he never had. My Mom’s light continues as a living gift to me and all who know her. Light and shadow go hand-in-hand to create form and beauty. Today, I am inside - every day. Looking for light. Like all of us, thanks to the pandemic, I am living in mostly physical isolation. But, I am also “inside” doing a lot of work mentally, emotionally, and spiritually to sustain my best self and try to remain a light of my own, to find the essence of this moment, to be present with it. A light defined by shadow. Shadow defined by light. I have captured these images of light and shadow throughout the inside of my house, the home where I was raised, where my wife and I are raising our children - the house still full of the light and shadow that so defined me. I am sharing these thoughts and images because I can. I am sharing them because I must. I am sharing them because it has been 14 years since I learned what darkness means and in that time I’ve also come to understand light. I hope you find your light in these dark times, and hold it dearly, grow it, share it, that it may be what guides you and those you love out of and beyond this shadow. This morning, in many ways, I had my first Communion. Well, let me clarify: I had my first Communion that I felt I could truly believe in - with full heart, mind, intellect, emotion, lived reality, and faith.

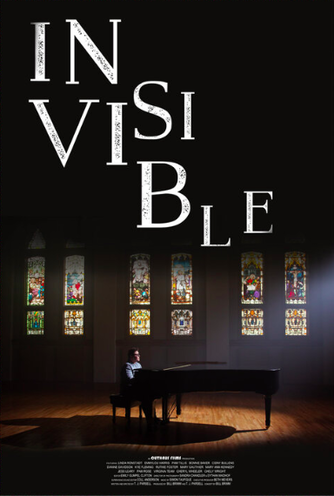

Growing up as a Christian, I have been through all of the key sacraments and milestones. Communion did, however, take two tries because as a Protestant in Catholic School, I was denied my first Communion when all of my peers prepared for and received theirs. I sat in the back pew and waited while they presumably opened their doors to heaven. I crossed that milestone as a Methodist some years later with markedly less fanfare. I never really resented my presumed lack of salvation in the Catholic Church - presumed damnation depending on how you chose to look at it. I just knew something didn’t make sense in my mind that as an 8 year old child I was denied this central symbol of the Christian Church while my peers partook. And, even as a child, I understood what its denial meant according to the faith of the people around me. Not for that reason only, but for the life I lived and the family I was raised in, faith usually didn’t cut it for my connection with a higher power. Action was what mattered. People - all people - are what mattered. Living the right life was what I could control and living the wrong one could never be overcome by quoting scripture or proselytizing my faith. This morning, I attended Church where a Church barely stood. I attended East End United Methodist’s service outside, in the grass, on a beautiful morning, with the tornado-torn bones of the old Church and the exposed rafters of its roof looming over us. I attended Church with several hundred neighbors, some of whom were members of the Church, many of whom just needed to gather after the tornado to be part of a community, to connect and find comfort. I still don’t connect much with scripture. I love the music and I do like a good and thought-provoking sermon. Today, more than anything, I loved being among people who all in our own ways are struggling with the tragedy of the week - whether our own tragedy or that of our neighbor or the tragedy of the loss of a Church. As the service wrapped up, the minister announced that in lieu of the sacrament of Communion, they would be passing out pieces of the broken glass from their shattered stained glass window - which until Tuesday told the story in light and glass and color of Christian Communion. The shattered shards they passed out even mirrored that of the broken Eucharist in my memory. This simple, beautiful, creative act amid destruction took my recent reflections on the Art of Church to a whole new level. In fact, this loving act, this sharing, this humble gesture, told the story of Christianity better than the window in its wholeness ever could have. It also didn’t require faith to believe. It was a symbol of the present. It was a symbol of the basic human brokenness we are all experiencing. It was a remnant of human creativity and storytelling and inspiration. It was the sharing of brokenness as a means of bringing us together. This is Church to me. This was a sacrament that I understand, and that I can believe in. I didn’t need Christian faith to find its transcendence. I have people. I have love. I have art. I have community. And, I have faith in these things. Communion.  We all must find ways to tell our stories, as best we can, in the ways that we can, at the times when we feel the strength to do it - but with a deep understanding that they matter. All of them. No matter how small we feel or how unique we believe our struggles to be or how fearful we are to expose our vulnerabilities, someone out there feels small, feels isolated, and is afraid to be themselves because no one would understand their story - a story like ours. This is the reality of the human story writ large and is the potency of the human story writ small. Far more connects us than separates us. Someone needs to hear our story so they can own and share theirs. This week, I went to a fundraiser for and watched a documentary called Invisible: Gay Women in Southern Music. It chronicles the stories of a surprisingly large number of wildly successful and talented gay women in mostly country music over the last several decades - women who have written countless number one songs, women brimming with vocal and musical talent, and women who have had to hide who they are to do the work they love and to share their gift with the world. I went in to the event knowing it would be an interesting story - just the immediate dissonance that comes to my mind as a Nashville native and a “son of the South” between the idea of gay women and country music is compelling. But, the film and the stories were so much more than I could have imagined. As I sat and listened to these women, as I laughed and cried with them and wondered at their talent and sacrifice and bravery, as I grew angry at the misogyny they have endured and the injustice that has forced their personal and career directions and taken away their individual rights and opportunities, as I heard their individual stories, each unique, I found myself deeply connecting with all of them. Let me be clear: we have seemingly nothing in common. I don’t listen to country music. I don’t play any instruments or write music. I couldn’t sing on key if I were paid. I am not gay, and I am a man. Their stories and lives moved me because I was reminded in a very intimate way that there are people like these women, hidden in places I never even think about, right here in my home town, who have worked and lived and endured daily in ways that I will never know. Their strength, their survival, their courage, and now their sharing of their personal stories will forever forward be a light in my being. They can never again be invisible to me, and those who still feel invisible are hopefully somehow less so. And, it’s not just about them, or me. These women who I had never heard of, never thought of, and otherwise would never have known - except for this documentary - have spent invisible lives quietly making my world a little closer to the one I actually want to live in. Most importantly to me at this stage in my life, they have made the world that much safer for my daughters to grow up in. I am indebted to them and deeply grateful. I can thank my friend Bill Brimm whose idea it was to encourage these artists to share their stories. But, to merely thank these women somehow doesn’t feel right. It’s not enough. It’s an embarrassment of my privilege and the relative ease with which the world has presented itself to me. And yet, it’s also all I have. So, let me thank them anyway - and really all of you who are reading this as well. Thank you for your story. Thank you for your art. Thank you for your willingness to share them. Thank you for your courage and resilience. Thank you for refusing to be invisible so that others may also see and be seen. I hope you will consider donating to help this important film make it to a broader audience. Please visit: https://www.outhausfilms.com/  My religious beliefs and practices are my own and are no longer rooted in the church. So, when I went to church recently by my own desire for the first time in years, I was a little surprised by the number of things the church and the experience actually reminded me that I believe in: I believe in architecture and the way the hardness of a stone floor can remind me of my physicality and groundedness - with cold feet and mild pain - and by contrast the way a soaring ceiling can pull my eyes and my thoughts upward and beyond my body and my self. I believe in vaulted gothic pillars and high, pointed arches that make me feel physically small with their scale and with their sense of history that reminds me that my time as part of the creative, human story is minuscule. I believe in dramatic lighting and its ability to add texture and fullness to the form surrounding me. I believe in music and the ability of a booming pipe organ or a delicate piano to inexplicably make my heart race or move me to tears. I believe in acoustics that can take the reverberations of a singing choir and sync them to the energy within me, melting my form as the sopranos take flight, my spirit in tow. I believe in stained glass and the artisan’s ability to filter natural light in such a way that I actually stop and pay attention to it, its source, relative intensity - the ways glass and light can make the artisan’s vision dance warmly on my retina in potent contrast with cool, bland, stone walls. I believe in the rose window and its circular reminder of the infinite. I believe in its fractal patterns that remind me that we are all parts of a whole - and in that whole, there is order. I believe in the creative, spoken word and its ability to analyze familiar parts of stories, fractals of human history, and twist and turn them in new ways to generate new reflections and understanding - to pique the intellect or move the spirit. I believe in symbols and metaphors that help us rethink and reframe small stories of daily life and large stories about the meaning of it. I believe in sitting still and being reflective. I believe in art. image: https://hiveminer.com/Tags/episcopal%2Csewanee From time to time, I will come across a piece of art I made many years ago somewhere out in the world - at someone’s house, a school, or someplace surprising. I don’t make much art anymore, so it’s always a nice experience. I’ve always said that it’s like seeing an old friend. Each piece comes from a particular time, a particular place, and a particular me.

A couple of weeks back as I was on the two-week countdown to my 20th college reunion, I got a text from my sister that included a painting I had made for my senior honors exhibition at Wake Forest University. I hadn’t seen the piece in 19 years. She had come across it hanging in a local soup kitchen down the street from where I grew up - which is the same house where I live today with my Mom and Wife and Kids. My sister and niece are having their joint 50th and 16th birthday party in the community room at the parish with donations to benefit the soup kitchen in lieu of gifts. The woman who worked there knew the painting had been done by “a kid from the neighborhood” but didn’t know anything more. She was thrilled to make the personal connection via my sister to me and back to the painting, and I was thrilled it still meant something to someone. Reunion. Now, a soup kitchen may seem an odd place to find a piece of art, but the painting was of a homeless man, face obscured, laid out on a park bench in the park across the street from my house - the space that separates my house from that soup kitchen. It was from a series of faceless portraits of people who lived on the streets and often slept in the park. Some of them I knew. Many of them my parents knew. Most of them came and went before their faces, much less their names, were familiar. This man was in the latter category. In my senior show, I was wrestling with the reality of these faceless, nameless people, and a sense of loss of my own identity and disconnection from my upbringing - especially after four years away, cloistered on a pristine university campus, the opposite of the grittiness that had so defined my neighborhood growing up. In some pieces, I wanted to draw attention to the body, the physical humanity laid out, so often with a face hidden from light or for comfort or perhaps a childlike sense of privacy. Regardless, most of those bodies were faceless. They lacked identity. I alternated the body portraits in the show with portraits of only faces, specific, with telling eyes and smirks and wrinkles and stories. For these, I didn’t show a body. I only showed the humanity that lives in the eyes and countenance of each of us. These were people. They had identities. Back to the present: Within a few days of getting that text from my sister, a few days closer to my college reunion, the doorbell rang at my house. As I approached, I scanned the woman in the window trying to see if I recognized her. We still get a lot of doorbell rings for a lot of strange and sundry reasons. As I approached to grab the key, I still wasn’t sure. But then, I locked onto her eyes - eyes I had studied more deeply than she will ever know - eyes that gave meaning to her portrait in my senior show. Eyes that still hung on the wall in my house. It was Luann. Over 20 years sober with a healthy body that suggested nothing of the toothless, colorless, emaciated addict I had known when I created her portrait. She came in and talked with my Mom and me for a good while, and I introduced my girls as they sat and listened intently. Life is still tough for Luann. She works hard to help others who have found themselves where she has been. The streets. The drugs. She talked about the day she had given up and found herself on the Shelby Street Bridge ready to jump before a police officer talked her down. My Father had stood on that same bridge with those same inclinations. She talked about my Dad and when she found out about his suicide. She visited and wrote us a note that day. I can’t imagine how such a thing impacts someone who has lived what Luann has lived. To bring it all even closer, she shared that Dad had committed suicide on her birthday, which was the day before his own birthday. She thinks often about him and Mom and their impact on why and how she is still here. Reunion. Luann said a lot. She talks rapidly. Passionately. Even feverishly, losing herself and forgetting that my young children were in the room listening curiously and with concern. So, when she left, we had to debrief. I called everyone back into the living room. We needed to talk about what it means to be addicted to drugs, what it had meant for Luann. We needed to talk about how amazing Luann is and what she has overcome - giving some context to her feverish monologue. We had to explain what Luann meant when she said “Satan lives in East Nashville” and why that is true for her, but that they don’t need to be afraid. Once I was convinced we had at least given the girls space to ask their questions, I took them into the kitchen and pointed up on the wall to a dry point portrait - scratched into metal with a sharp tool, inked, and printed on paper - of Luann 20+ years and probably 50 pounds ago. Her emaciated face, crevassed and deeply wounded in a way that suggested eternity but no specific age. But, her eyes - once you found them sunk deep in her hollowed out sockets - were still there shimmering. These were the same eyes I met in a new visage, in a new body, in a new life at the front door 23 years later. Reunion. Last weekend, when I finally got to campus for my college reunion, I went by the art studios and the first face that I recognized was my former painting instructor. We’ve been in touch here and there over the years, at least enough to feel connected. But, after a pause and a couple of slow moments of recognition of my aging countenance followed by a big hug, I couldn’t wait to tell her of this sequence of events that had curiously led up to my visit. How it was that painting that I hadn’t seen in so long, that portrait that I see every day of that person I hadn’t seen in so long, that art I had wrestled with 20 years before, that work that had helped me explore my story, create my first art show, helped me find my voice through art, start my creative journey - that those experiences that happened in a few undergraduate art studios 20 years ago still mattered deeply to me, and to at least some people I don’t even know about. Reunion.  excerpted from Creating Matters: Reflections on Art, Business, and Life (so far) Sometimes our “finished” work can actually be what prevents us from creating new work. We get stuck. We stop listening. We stop learning. As artists and creators, we often believe our work is inherently precious and valuable and meaningful because…well… it is to us. Well, it’s not. And, thinking so is a trap and counter to the idea of the creative process. The most important lesson I learned as a developing artist was accidental, and if I hadn’t been forced into it, I would have almost certainly continued to hang on to my every “masterpiece.” I had never built anything. I had never worked in a woodshop. I don’t measure things particularly well, and don’t pay that much attention to detail. So, building things was not exactly in my creative wheelhouse. So, of course, when I decided to build something in my first sculpture class, I went big. I’ll spare you the details of my early efforts at conceptual art, but the piece did make it into the student show! Enter ego: Yes, I am Artist. Brilliance. Can you feel that!? I went home for the summer while the Student Show wrapped up and when I came back, there was my masterpiece, sitting in the hallway. As I stood looking at it, one of my teachers approached and said: “You have to get that out of here.” Apparently, everyone didn’t feel it should be a permanent installation in the studio hallway. And, apparently, it didn’t fit through any doorways I could reasonably get to. Hmm…what to do!? The answer was back in the sculpture studio, where it all began…and, it was a “saws-all”. After the initial horror of the thought of destroying my piece, I plugged in the saw and gingerly started to cut. Within moments, I must have looked like the artist version of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre. I ripped that thing to pieces…sawing…splintering…crashing…cutting…and almost certainly bleeding. And, in the final act of destruction, I dragged my masterpiece piece-by-piece outside and slung it over the side of the dumpster. Holy crap that felt good. It was humbling…and then completely liberating! I have created more freely since that day. Fast forward fifteen years or so, and I was helping start Zeumo. While we were still struggling to get distribution in a number of large school districts, we were presented with a new opportunity: “We need this kind of app in hospitals.” We were failing slowly in education and had to be humble enough to acknowledge it. We also had to have the courage to try something else, to keep iterating. Long story short, we seized the opportunity and, having invested countless hours and hundreds of thousands of dollars with a vision for helping high school students, we took the proverbial saws-all to the education app. Humility is not about accepting loss or defeat. Humility is about owning the process of exploration and finding the strength and energy to keep doing it. It’s about putting failure in its proper place in our art and in our lives – right at the heart of what we are creating.  Years ago while backpacking through Europe with some friends, I visited the Palazzo Spada in Rome. It must have been something we read about in “Let’s Go Europe” because otherwise I’m not sure how we got there. Anyway, Palazzo Spada is famous for its incredible forced perspective gallery created by Francesco Borromini. In the midst of the density and limited space in the heart of Rome, the gallery gives a momentary sense of depth and grandeur akin to what one might find in a much larger country estate. It has an 8-meter long corridor that appears to be a considerably more grand 37 meters. Its centerpiece and visual destination is a “life-sized” sculpture that is actually only 60 centimeters tall. It sounded crazy, so we were definitely intrigued! When we first got to the palazzo, I wandered up to one long, beautiful corridor lined with columns and with a statue at the end. Such a site wasn’t particularly unique or exciting after a couple of months of traveling through Europe. We had seen probably 10 of them just in Rome. But, we were there to see the fake one! This one was the real deal, obviously not Borromini’s work. Then, something weird happened. As I turned to keep looking for Borromini, I was suddenly disoriented. Wait…what the…hold on… I momentarily lost a sense of where I was and even how big I was related to the things around me. Distance was a scramble. That long corridor got short then long then short. The sculpture was life-sized then tiny then… My eyes seemed to see one thing then another and then back to the first. I tried to focus. My mind tried to make sense. But, my eyes and mind were wrestling with a carefully crafted lie (Borromini actually worked with a mathematician to help create it). The illusion starts with controlling your vantage point. It entices you to the spot where you need to stand to perceive its fabricated truth. Once in position, it manipulates your horizon and narrows your vision toward a single vanishing point. It then constructs the objects around you relative to the truth of that horizon and vanishing point, closing off a broader world of scale and perspective. As long as I unwittingly obliged its subtle and unseen rules, I saw what Borromini wanted me to see. But, if I changed my vantage point, things shifted. As I moved, I regained control over my horizon. A step left…right. Squatting. Getting on my toes. My eyes adjusted away from Borromini’s very particular vanishing point. The things I knew and understood about the relation of objects in the world began to reclaim their rightful logic. The perspective was no longer forced. I was back in control because I had seen it for what it was. Beyond art and Borromini’s clever trick, forced perspective manifests in life in at least two extraordinary and paradoxical ways: 1. In the negative, it is the tool of the abuser, the occupier, the oppressor. It is the carefully constructed, highly controlled, believable version of reality that is motivated by the destruction and control of the other. It shifts the rules, norms, and logic so fundamentally, yet subtly, (mathematically in Borromini’s case) that the oppressed colludes in his own oppression, the victim blames herself. Accepting plausibility as truth. Normalizing external definitions that destroy internal foundations. Disorienting to the point of confusion, uncertainty, and weakness. Forced. Perspective. 2. In the affirmative, on the other hand, it can actually draw us out of disorientation. It can focus and clarify. Provide control. It can be the tool that helps liberate us from the abuse and oppression described above. When life is in fact chaotic, unsure, unfocused, and scary, forcing perspective can be a way to survive, manage, and direct limited energy. When you are struggling, it can adjust your vantage point toward things that matter, things that you can control. In this sense, counter to its negative application, it can reorient you to your fundamental truths and strengths. It asks: Is your horizon set in relation to the things that matter most to you, or a construction built around some other illusion? Forced perspective is part of our daily lives. The fine line between perspective as something we control versus something that controls us is fundamental to our relationship with our selves and the world. So, we must recognize it, name it, create it, and own it every day. Otherwise, we may be forced to live a life defined by someone else’s perspective. I was on my way back from a long one-day trip to Phoenix (doing the startup hustle) and an old friend popped into my mind.

Scot is a musician. He was in a band. And, they were very close to making it big. They got airplay across the country and internationally. They had a die-hard local following. (I was a fan before I ever met him.) They were traveling all over the place building strong pockets of fans everywhere they put on their incredible live shows. They were hustling. Momentum was building. But, they didn’t become “rock stars.” Knowing Scot, I am not sure that is even what he wanted. I suspect the rock star designation for most musicians is an inaccurate, or at least narrow, moniker to try and capture some external notion of success or validation. Scot loved music. He loved the camaraderie of the band. He loved performing. He loved creating. He loved that people loved what he was creating. And, now years later as a college professor, he still does. Little has really changed. Scot’s creativity didn’t live within his music. Music was its outlet. Now, it’s higher education. For years, people have chuckled in confusion when I tell them I have an MFA (that I am still paying for) from one of the most respected, if not widely known, art schools in the country, Cranbrook Academy of Art. Clearly, I wasted my time and money. They assume I was forced to change “careers” because art was obviously a dead end. What could art have to do with my work? With education reform? Entrepreneurship? Well, everything. Creativity is a transferable skill; the creative process a discipline. Where and how we choose to cultivate our creativity is fairly unimportant. However, where and how we choose to apply our creativity directs our life’s creative journey. Now, as an entrepreneur I feel more than ever like Scot (or how I imagine him early in his music career), like a musician hustling to get his product out there. I want to share it with people. I want people to use it. Give feedback. Enjoy it. Challenge it. Find meaning in it. And, yes, pay for it. I want all of this so that I can continue to create in this space. But, I also want to know what I am creating matters. And, if it doesn’t, I want to know how and why so that I can make sure it ultimately does. Like most artists, musicians, entrepreneurs, and the various and sundry others with the driving need to create, I don’t really want to be a rock star. I want to matter. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed