Complicit with the unbearable lightness of privilege (see previous blog), oppression is a constant burden. Like privilege, when unacknowledged by the oppressed, it becomes a fact of life unquestioned and unchallenged as it is unknown. Instead of manifesting in lightness, oppression is weight. As I think I have made clear, I fall in the privileged category. I do not know oppression first-hand in any way, shape, or form. I have merely observed it through my upbringing and my work and I have read and learned about it as a way of deepening my understanding of my own privilege. I fought against it every day when I worked with youth. The depth and breadth of assumptions and judgments they had about their own poverty, blackness, age, and even neighborhood were stunning and troubling – even to someone who thought himself enlightened. In fact, their internalized negative assumptions were the ultimate barrier not only to achieving the dreams they still had individually (their oppression yet only partially internalized) but also to the improvement of our schools and community. Their oppression was both individual and structural, implicit in their schools and community and fueling their early process of internalization. We had to start our work with every young person by helping them think critically about what they had internalized and how that impacted the choices they made and the opportunities they sought. Internalized oppression changes the way we dream. I recall one simple and brief conversation with a young woman who lived in public housing in a rather chaotic family situation who had told me she wanted to be a dental hygienist. I told her I thought that was great and asked her why she wanted to do that. As she talked, she expressed a broad interest in dentistry, the science, the business, the people. So, I asked without thinking why she didn’t want to become a dentist rather than a dental hygienist. It left her somewhat dumbfounded, which left me dumbfounded. It had never crossed her mind. It was the first thing that crossed mine. Aside from this rather simple example, our work trying to liberate each other of our oppressions (and privilege for me) was often brutal work and had to be done in a safe way and in a manner in which we had time and space to deal with anger and confusion and more questions that it spurred for them about themselves, about the adults in their lives, the systems that were supposedly there to support them. As they became more critical and more liberated, they also began to feel that burden of oppression more fully. We were externalizing it. They went from living but never seeing it to seeing it everywhere they turned, while still living it. This was powerful work, but it was dangerous work. These youth needed to see their oppression so they could begin to liberate themselves from it, reclaim power from it, but it wasn’t something we could immediately just go out and change. We had to start small and individual and work from there. While all of my youth and most of my community could point at and name experiences where they were treated differently because of their race, or their age, or their perceived income or whatever, they mostly processed those at the level of the interaction, focusing on the individual experience. They never saw the system that was supporting their marginalization; the structures that consistently and persistently delivered the same type of negative message for everyone like them. One of the stories we used to help process this growing awareness of systemic and institutional forces was the Parable of the Boiling Frog. While simple and fairly grotesque, the Parable of the Boiling Frog illustrates the fact that a frog that is dropped into boiling water will scramble for its life to get out. This obviously makes sense to most of us and is how we would react to such pain or danger. On the other hand, if that frog is dropped into room temperature water that slowly rises to a boil, it will never even try to escape. The frog will make incremental adaptations to survive the environment that ultimately leads to its death. This is the story of internalized oppression. We adapt to messages about our worth, about our possibility, about the quality of our character or our family or community one message at a time. And, when those messages all align in a way that consistently and persistently tells us we are lesser then we begin to believe we are lesser. At some point, we accept the fact that we are lesser. We accept our slow death without ever even recognizing it. So, how do we get out of that slowly boiling pot? Even as personal enlightenment and liberation unfold, the systems and structures of oppression are generations in the making and will be generations in the dismantling. Just because we liberate our minds doesn’t mean the systems are ready to change. We have to transform our personal liberation into something that impacts the world around us. Lest we become overwhelmed by this responsibility, we must remind ourselves that we have the chance to impact the world not just through grand social actions but through every interaction. We have the power to open hearts with every conversation, liberate minds by modeling our own liberation, by putting our own challenges and development out there for others to see, to find solace and motivation in. image from: https://www.shapeways.com/product/J5WVPUPLB/triple-gear

0 Comments

I like words. I believe in their power. If you read my blog that should be pretty clear. But, yesterday I was reminded that years before I was ever writing on a regular basis, I was trying to instill the power of words, not just for communication, but also for understanding the world, where and how we fit in it. I had lunch yesterday with one of the first youth I ever worked with, James, Class of 2004. He has moved back to town and we were catching up and thinking through networking and that kind of thing. In moving, he had left a job where he was working with students in an alternative school, young people from the same kind of community we had worked in, but more acute, more intense. I was glad to know he had translated some of his teen experiences into doing this kind of work, but I was stunned when he told me he actually used one of my workshops/discussions in his own work, more than a dozen years later. I couldn’t believe he still remembered it. It was one of those conversations I had facilitated almost certainly when I had hit peak frustration, and you never really know how those will work out! When I worked with youth, we talked about language pretty frequently. We discussed language in terms of communication, power, privilege, and how we need to keep asking “why” to blow up racial, economic, and cultural assumptions. But, this time, as James reminded me, I picked four specific words. I picked these four words because I felt my team needed them in their vocabularies. I picked these four words because they articulated the things we felt, experienced, and saw every day in our community. I picked these four words because we couldn’t get anywhere with our work, with exploding issues of oppression, with becoming youth advocates and organizers, with trying to change systems without understanding and attacking them. So, what were the words? Apathy Complacency Lethargy Atrophy These aren’t THE four words, or the BEST four words. They were probably just the four words burning in my brain as I walked to work that day, stewing on how to incite and awaken our team and our community. We discussed what they meant, according to the dictionary and our localized take. I asked if they had any examples. I asked them why they thought we were discussing these words. Ultimately, I asked them to take the next few days and to keep these words at the top of their minds, to go back home, to school, and to their neighborhood and watch for these words to surface in their experiences. I asked them to bring those observations back to the group. How do these observations relate to better strategies for reducing the use of payday loans and other predatory lenders in our community? How do they enlighten pathways for increasing college access for students in our schools? Too often, we look at words merely as a medium for expressing our thoughts, communicating to others, written or verbal. We don’t spend enough time thinking of the power of words to help us formulate our thoughts, to liberate us, to help us name and identify and begin to understand our oppressions or opportunities. We don’t think about the intellectual and creative force of words that are never written or spoken, the words churning in our minds as we seek to navigate and understand our world. These four words for me, on that day, at that time, with those young people were the most dangerous words I could think of. They were the words that could determine a future, define a community. They were the words I needed our team to own and understand, to shock our team into a more creative place, to liberate us from the words themselves. I am indebted to James for reminding me of this lesson. I am in awe and inspired by his actually taking them and making them part of who he is and how he helps others navigate their worlds. Now you take them, keep them top of mind, and try to recognize where you see them in your world. Hopefully, recognizing these four words can incite us all to make ourselves and our world better.  This is the expanded Q&A interview with Anderson Williams that appears in Volume 25, No. 1 of the Youth Voice issue of the National Dropout Prevention Center/Network Newsletter from page two. Q: On Page 1 of our Newsletter, you reference what led you to create the youth voice framework Understanding the Continuum of Youth Involvement. You say that the Continuum can help educators avoid some of the common pitfalls in executing youth engagement initiatives. What are they? A: I think the reality is that when you look at the examples in the Continuum, you’ve got young people making a broad range of decisions, and implementing [projects] based on those decisions. There can be a couple of places where you can fall short: one is offering young people who’ve never practiced decision-making the opportunity to make decisions, and then expecting them to do it with 100% success—that’s one problem. And when the project is not successful, adults rescue the students so that the students don’t ever understand consequences, or feel accountability for their decision-making. They either aren’t allowed to fail at all or are allowed to fail in an unproductive, unsafe way. [If students are going to fail], it needs to be in a safe environment where they learn and understand not just the results related to accountability, but the nature of the decision-making that got them there. So it’s failure without learning, and that’s another pitfall that really pushes young people away. Failure with learning isn’t really failure. It’s learning. Q: What constitutes a safe environment for students? A: It’s about trusting that somebody has your back, that somebody shares your interests, and trusting that somebody can tell you the truth in a way that’s respectful and is about learning, and shared goals. It’s all of those things that you’d expect in any trusting relationship—whether that’s within a family, in a community, the workplace, or if it’s a teenager in a school. Q: Is there a temptation for an instructor to jump to the “Engagement” column of the Continuum and try to start there instead of building up to that achievement? A: The way that I use the Continuum--and the reason I created it—was to say “be honest about where you are and start there.” The Continuum is not designed as a hierarchy: it’s a strategic growth map on how to get to engagement. Because if young people have previously only been participants, they’re not ready to be engaged fully; you don’t have a relationship there to engage them successfully and effectively. [Young people] haven’t developed the tools, practices, or understanding of “cause and effect” with decisions, accountability, results, work and rework, and all of the things that go into being engaged. You aren’t ready and they aren’t ready Q: What do teachers and students need to keep in mind when venturing into a youth engagement initiative? A: It would be a stretch to take someone who was, say, a successful assembly line employee, and suddenly make them CEO of the company and tell them to “go do it and bring everybody else along.” It doesn’t mean that an assembly line person couldn’t become CEO, but you don’t make that jump without some investment, practice, and learning over time because the skill sets are different—even though the context is theoretically the same. How you engage in the classroom requires a lot of different skill sets on the teacher’s part, but also on the student’s part, too. Youth engagement is not just a change in practice for the teacher, but a change in practice for the young person, as well. And that’s why on the Continuum, the emphasis on accountability is detailed for both teachers and students at every level of the work. Q: But a student can’t expect that engagement will be a component of every class they attend every day, can they? A: That’s the reason why youth engagement needs to be a core strategy in education. And that means that engagement isn’t something that happens in one classroom—it happens across the educational environment. And that’s one of the pitfalls to [youth engagement] efforts that have burned teachers— and principals and administrators—who have put their necks out to engage young people. [Youth engagement] has not been systemically understood as a strategy for educating young people. So, it hasn’t really been safe for adults or young people trying to make it happen. Q: If engagement is part of one class a student takes, and not part of another, couldn’t that cause a student to become further disengaged in courses that don’t embrace engagement? Doesn’t every instructor want to be the “cool teacher” who’s always able to engage their students? A: I’m glad you brought that up, because youth engagement is not about “cool.” That’s a misconception. It’s a fundamental misunderstanding of what engagement is, and it’s a conversation I’ve had many times with adults. Kids know which of their teachers are trying to be “cool,” and trying to be their friend—and those aren’t the ones they’re engaged with. With the kids I’ve worked with, I made sure they understood that I wasn’t their “friend,” [but their partner and supporter in whatever we were trying to accomplish.] I’m generally a friendly and easygoing person, but in this relationship, the engagement [with my students] was about a shared goal, discipline, and solid, trusting relationships—we were working together on something. I always told them I would work as hard for them as they were working for themselves. But, that as soon as I was working harder, we would have to stop and assess our relationship, focus, and work together. Students may like some of those “cool” teachers, but if they’re not teaching them, they know it, and they’ll call you on it. It’s really important to note that engagement isn’t about popularity, it’s about effectiveness. Students are smart and intuitive about this. Q: The teachers I remember from high school and college whom I learned the most from, they were all pretty serious about what they were teaching. A: Authenticity is absolutely at the core of it. If you think about who your really great teachers were, although some of them might have been cool, some of them were absolutely not cool. There is research out there that talks about how the nature of the teacher-student relationship guides and determines how effective that learning environment is, and what subjects kids end up being drawn to. And it’s not necessarily the subject, but how it’s being taught, and how you and the teacher engaged in that learning together. Q: You’ve pointed out in our conversations that there’s a difference between a “youth” and a “student.” A: We have this really bizarre structure where we call a 15 year old kid a “student” from 7:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m., and from 2:01 p.m. to 6:59 a.m. the next day, he’s a “youth.” The role of student and the role of youth are fundamentally different. They have different expectations. The adults they interact with behave differently, have different training, and provide different opportunities. And what adults do in the “youth” world and what they do in the “student” world typically don’t connect. So we create these multiple systems because it’s how we’ve approached things historically, rather than thinking about what does it mean as a city, for example, to provide good opportunities for youth to grow up here? Q: So these terms aren’t interchangeable? A: In no way, shape or form except that [you’re] referring to the same kid. Teachers don’t learn about youth development, youth development people don’t know what’s going on in classrooms, afterschool programs aren’t tied to what’s going on in schools, and [adults] in the classroom don’t know where kids are going afterschool. Q: Service-learning has become a popular way to engage students. Is that an effective way to introduce students to youth voice and engagement? A: It certainly can be. I’ve seen service-learning in a variety of forms: I’ve seen it where a box is checked and where the kids only participate and do what they are told, or, at other times, where the kids have only nominal voice, and still others where service-learning is transformative, where there is true engagement. Service-learning as a tactic for youth engagement can be really transformative—for student and teacher—with the right approach and philosophy behind it. The devil is in the implementation details. Q: Going back to a term you referred to earlier: how do you introduce students to the concept of accountability? A: If you watch young people interact with each other, there’s a whole lot of accountability [because] they’re approaching each other from an equal power position. There is a sense of mutual responsibility. It reminds me of a quote I read somewhere to the effect of “accountability is what is left when responsibility has been subtracted.” Students don’t have much responsibility in school. The structure of education leaves them only accountable to sit down, stay out of trouble, and [get good] test scores. They’re not responsible or being held accountable for offering ideas to improve the school, to help prevent bullying, for mentoring younger students in their school. They don’t see their role in creating a positive school climate or maintaining the cleanliness of the school. Without any real responsibility, they are merely held accountable for taking the test, making the grade, be a decent kid and stay out of trouble. If they don’t do those, then there may be consequences. Q: You often hear students complain that they’re never going to “need” a certain course or area of study because it will have no bearing on what they want to do in life after high school. Why is youth engagement important in a longer view? A: Youth voice and engagement is about relationships, about learning how to navigate institutions, and learning how to communicate with adults, now and as young people move forward in their education or even careers. How do you ask good questions? How do you deal with uncertainty? Ambiguity? How do you have the confidence to connect with others when you’re on a strange campus that you’ve never been to before? How do you make decisions? All of these things have to do with how engaged you are in school, and in life before you get to college, for example. There are kids who are returning home from college because they’ve never been in an uncertain situation, or in a place where adults weren’t controlling the environment. They’ve never been in a place where they’ve had to make decisions that can have a significant impact on their education. And so they get to college and have to figure out what courses to take, they have to figure out their financial aid, where their dorm room is, and meet the person they’re going to be living with. They haven’t done any of that and it’s incredibly scary, and they don’t have the tools. Q: There’s a lot of discussion of issues like Common Core at all levels of government. Do you think that youth engagement as a core value of education will ever get that kind of attention? A: I don’t see anything yet in any of the discourse I’m aware of that indicates a shift toward the development of young people as a focus in education. If you look at what the dialogue is, and what the debate is about in this country, it’s about twists and turns in the institution of education, it’s not about learning, and keeping up with all that we know and continue to learn from science about how learning happens. We’ve built this superstructure that is the education system, and we’re creating all kinds of pedagogical debates and philosophies around Common Core issues, while remaining beholden to the same old structures and systems. There are all these conversations and policies trying to shift the rules in a system that has never decided that its goal for improving is actually to engage our students better in learning. Q: You’ve put forth some ideas and concepts about education that people might not be comfortable with. Some of your ideas could even be called subversive. A: (laughing) Well, they are. They are! They’re “subversive” because we’re really comfortable in education in running the Institution of Education—we’re not really comfortable in engaging students. It’s the context of a navel-gazing approach where we keep looking and tweaking The Institution as it exists, and iterating off The Institution as it exists without ever coming back and asking the fundamental questions about our relationship to young people and our goals [for them]. It is subversive because everybody is sitting comfortably in institutions of education and school districts that have failed chronically—particularly in urban areas—for generations, and a bureaucracy that keeps them from fundamentally having to change their approach. Q: What do you see for the future of education and our students? A: I think that the monolithic “one size fits all” school district is a model that is a thing of the past. Some are going to dismantle more slowly than others, and for a range of reasons including a lack of faith in government, and shifts in politics more broadly. I think that the centralized source of knowledge and expertise is no longer a part of our sociopolitical and cultural belief systems. If charters [charter schools], for example, are managed and learned from appropriately, and are they are successful, there are opportunities for more input and more learning than there is with one central gatekeeper and system. If you’ve got 10 charters in your district and a central office [then] you get to learn from perhaps 11 different, nuanced approaches to education, rather than one. To me, that’s how we can do better. But, districts and charters don’t often have that kind of relationship unfortunately. Charters aren’t a panacea. They are an opportunity to learn. I’m hopeful we can learn. Some of the best charters in our district [Metro Nashville Public Schools] are criticized for being “overly disciplinarian,” and for having an almost military type structure. But, the thing is that kids don’t innately dislike that. If they trust you, and you share a goal, and [this structure] is about achieving that goal, and they understand it, then they don’t resist that kind of thing. What kids resist is “command and control,” from people they don’t trust force-feeding them an idea they haven’t bought into, and don’t have a shared interest in. Once you’ve built a shared interest and a relationship of understanding, kids will engage when they understand that it’s part of getting them where they want to go. by Teri Dary, Anderson Williams, and Terry Pickeral, Special Olympics Project UNIFY Consultants

In our last blog, we focused on what creative tension means in the context of relationships between young people and adults in our schools. We outlined core principles and assumptions that are critical for this work, and discussed how the roles for young people and adults shift in the creative tension model. This blog presents a series of real-world examples that demonstrate the use of a creative tension in carrying out intergenerational work within the school context. There are a few key ideas to keep an eye on. First, each example shows youth and adults working toward shared goals, with young people being viewed as meaningful contributors and partners in the process. Second, supporting their shared goals, you will see how personal goals and aspirations align with and support their collective work. Finally, each values the other’s experiences, perceptions, skills, beliefs, and ideas and understands that they are critical to achieving personal and shared goals. Ultimately, these examples are intended to demonstrate the varying ways schools and systems can support and nurture collaboration and shared outcomes between youth and adults. Curriculum and Instructional Design A high school chemistry teacher created a more connected learning process by organizing unit information on his white board by the content standards, and then highlighting for the students where each of these standards were addressed in labs, quizzes, class activities, homework, and tests. Rather than simply posting the standards, this is an active, dynamic process to help students understand how each discreet learning element ties to the bigger picture and connects to other learning. These connections then play out in quizzes, homework, and summative labs, which guide students in determining their level of understanding and focuses on demonstrating mastery rather than just obtaining a grade and moving on. Students are making decisions about how and when to study based on this knowledge and are better prepared to guide their own learning. Alternately, the teacher continuously engages students in the process of learning from design to assessment, helping them better understand how everything fits together and their role in both teaching and learning. A core component of the structure for this chemistry class is having students work in groups that stay the same throughout each unit. Groups are encouraged to apply critical thinking in labs and class assignments by altering variables and designing their own labs to produce desired results. In ensuring all students are contributing team members, everyone in the group is responsible for teaching as well as learning from others in the process. The result? Creative tension between the students and teacher in working toward shared goals has substantially increased learning, engagement, and ownership of the teaching and learning process by both the teacher and students. Basic Lesson Planning We were reading “A More Beautiful Question” by Warren Berger recently and he shared an example of a teacher who recognized the challenge of engaging students when teachers ask all the questions (and hold all the answers). He wanted students to ask the questions in class, so they would own the process of finding the answer. So, for one lesson, instead of asking “how long will it take to fill that bucket with water” and having the students complete a worksheet with prompts and places for calculations and so forth, the teacher took a video, a long video, of water dripping into a bucket and showed it to his students. It was mundane and redundant and monotonous and felt weird, like nothing was happening. Finally, almost exasperated, the students asked for themselves: “how long is it going to take to fill that bucket!?” Now that the students had asked, they also actually were intrigued and interested in finding out. As a result, the students built their solution not only from their own question, but from the shared experience of watching that water drip into the bucket. They wanted an answer, so they worked to find it. Parent Engagement One high school we worked with, like many around the country, was experiencing significant demographic shifts with a huge influx of students and families from Latin America. They knew many of their parents did not speak English, but also knew that they were sending home important information about the school, about their students, and so forth that the parents could not read. For starters, they knew they needed to translate their materials into Spanish. They contacted a nearby university and through their Multicultural Center found college students eager to assist. However, the university students requested that high school students in Spanish classes also be engaged in translating the various communications to parents. As a result, the school, Spanish teachers, high school students, and college students all worked together, sharing and enhancing each others’ skills and awareness of the issue. To do so required some changes in process for each and required creative tension among all to make it successful. Ultimately, the university students working with a countywide nonprofit established English classes for Latino families. School Governance A high school leadership class was designed to provide students an opportunity to learn and practice valuable leadership skills by addressing issues in their school and community. One group of students in the class decided they were concerned about students’ ability to transition from the overly structured high school environment to the unstructured college environment. They had never experienced or practiced the decision-making that comes with such freedom. To address this issue, they decided seniors should be able to have open campus lunch, to practice some additional independence. The group worked with their teacher to review board policy and school rules, surveyed local businesses, and developed an open campus proposal. (This process in and of itself was also an exercise in independence.) The principal gave permission to work on the project and provided a set of criteria that would need to be met. Additional provisions were made to address concerns raised by teachers, community members, and local businesses. Based on this work, the students developed a district policy and succeeded in getting the policy passed by the school board, allowing seniors to leave campus during lunch. Working across systems is inherent to working intergenerationally and requires the ability to generate creative tension rather than destructive. Complaints or protests or otherwise by the students could have just as easily shut down the opportunity and the solution they sought. Working together allowed it to come to fruition. Additionally, this process and the additional trust and responsibility provided to seniors generated improvements in school climate more broadly. School Leadership A group of high school students working with a community based organization began to research and ask questions about why only a handful of students at their school went to college each year, when they knew the numbers were vastly greater at other public schools across town. When they first raised the subject with their principal, she was immediately defensive and tried to shut down any avenues for continued research and organizing. In response, the youth requested a series of meetings with her to discuss the issue, their research, and their concerns; just with her, no pressure and no real need to be defensive in front of teachers, colleagues, etc. Ultimately, the principal became the schools’ biggest advocate for college access and, working with her students and her counseling staff, doubled the number of students who made it to college in one year. Their work together was highlighted in a documentary called “College on the Brain.” With their initial questions, the students had accidentally created a destructive tension scenario, because the principal did not feel safe to have the discussion without going on the defensive. Reaching out and clarifying their desire to work together and articulating how improving college access could be a shared goal for students, counselors and the principal, the students moved toward creative tension and enabled a powerful example of intergenerational work. School Climate Students, parents and schools around the country have created and implemented R-Word campaigns to eradicate the derogatory use of the word “retard” in their schools. With the goal of making schools safer and more equitable for all students, an R-Word campaign sends a powerful message, but one that is only made powerful by the commitment of students, teachers, school leaders, and parents. In other words, it is a community effort. Typically, these campaigns begin as a conversation between students and teachers who then get commitment from school administrators. In developing a plan and a kickoff on Spread the Word to End the Word Day, the school community works together to create banners and posters, to get food, to get commitment signatures and so forth. As a result, schools that have gone through this process of working together and worked toward a more inclusive school environment have seen dramatic improvements in school climate and reduction in bullying. There are clearly many ways each school can begin to incorporate creative tension to enhance intergenerational work. And, they all begin with a shared goal among young people and adults around a creating an engaging teaching and learning environment where all students and adults have opportunities to contribute meaningfully. The key is to begin. Start from where you are, start small, and seek continuous improvement. In our February 18 blog, we clarified the distinction between creative tension and destructive tension as they relate to our relationships and our work in schools. And, our example was focused on the relationships among adults in a school.

In this blog, we focus on what creative tension means specifically for the relationship between young people and adults in our schools. For starters, we cannot develop real creative tension unless we change the way we see young people and their role in education. What would happen if we decided our students were our partners in education, rather than mere recipients of it? What if we believed they had something to teach us? To teach each other? What if our goals were shared goals and our accountability collective? What if education were intergenerational work? How would this change the relationships between students and adults in a school? Imagine a student and a teacher holding opposite ends of a rubber band. As each pulls away or comes closer, the tension in the band changes. It moves. It makes sound. It has energy. But, if one pulls too hard, the energy generates fear and uncertainty in the other (What happens if she lets go? I’m gonna get popped!). Movement becomes limited. The energy becomes bound. The band is taut. It is not productive. This is destructive tension. Now, what happens if one relaxes the tension on his end? The band goes limp. It has no energy, no sound, no movement. It sags. What does this mean for the one left holding it? What about the one who let go? This lack of shared tension (energy) results in destructive tension. In creative tension, the energy each person contributes is dynamic and dependent upon each individual's personal goals, their collective goals, their relationship and their trust in each other. It is constantly changing. So, to remain productive, we have to constantly communicate the tension we need and listen to others as they do the same. Our relationships then must become more dynamic and multifaceted such that the right tension becomes both intentional and intuitive. So, what does intergenerational work mean? Intergenerational work is neither about young people nor adults. Intergenerational work is about the work. It is a change strategy that believes that different generations bring critical experiences, perspectives, skills, and relationships to the work that the others do not. And, to effectively achieve our goals, to do our work, we need all of us working together. Perhaps the most established model of intergenerational organizing comes from Southern Echo in Mississippi. While their community organizing model does not directly translate to schools, its descriptions of what intergenerational means are informative. According to Southern Echo, intergenerational means: 1. Bringing younger and older people together in the work on the same basis. This principle is simply about building a collaborative approach to the way our schools function. It is as true for intergenerational relationships as it is for relationships between adults. Maybe that's why we struggle with “motivating” students. Rather than imposing our goals and ways of functioning on students, we should engage students with us, not simply try to convince them to do what we want them to do in the ways we want them to do it (on our basis). There is no creative tension in that approach. Our schools could follow a wise mantra often repeated by the youth leaders of Project UNIFY: “Nothing about us without us.” In this, there is creative tension. 2. Enabling younger and older people to develop the skills and tools of organizing work and leadership development, side by side, so that in the process they can learn to work together, learn to respect each other, and overcome the fear and suspicion of each that is deeply rooted in the culture. This principle means that each young person and adult has the opportunity and obligation to bring his skills and develop his weaknesses for the betterment of the collective. The right tension depends then on the positive and negative expectations one has for self and others. For example, a student may have higher expectations for himself (+) and but has a teacher with lower (-), leading to a (+-) relationship. This dynamic happens just as readily in the opposite direction as well. As a result, energy and strategies for skill development and creation of goals are misaligned and destructive tension rules. Maintaining creative tension in intergenerational work means nurturing collaborative partnerships that build upon inequitable skills, with youth and adults both learning from and teaching each other. The roots of this dynamic between youth and adults, however, are deeply rooted in our culture, so addressing them effectively is indeed counter-culture and demands fidelity and consistency, and a touch of a counter-cultural spirit. 3. It is often necessary to create a learning process and a work strategy that ensure younger people develop the capacity to do the work without being intimidated, overrun or outright controlled by the older people in the group. “Control” and “exercise of authority” are great temptations for older people, even for those who have long been in the struggle and strongly believe in the intergenerational model. Culturally, young people are taught to defer power to adults and adults are typically rewarded personally and professionally for acquiring power. It is deeply rooted in our education systems and our economy. So, breaking out of that dynamic does not happen quickly or easily. Having a shared intergenerational model and shared understanding of and commitment to the resulting creative tension is critical for the work to take root. It cannot be ad hoc. Young people and adults both need to own it, respect it, celebrate it, and call on it when they feel that it is not being executed with fidelity. There are some important assumptions that are inherent to this work:

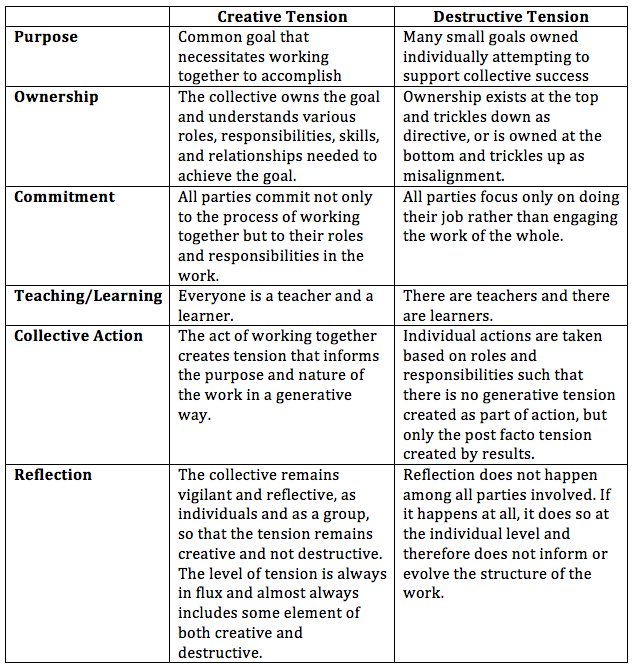

In our next blog we will focus on a couple of case studies where creative tension and effective intergenerational work have improved school climate and outcomes. Written by: Anderson Williams, Teri Dary, and Terry Pickeral originally published by the Learning First Alliance The problem with public education is that there isn’t enough tension. The other problem with public education is that there’s too much tension. And, perhaps the biggest problem is that both of these are correct; and we don’t distinguish between creative tension and destructive tension. Without distinguishing between the two, we cannot intentionally build structures and relationships that create the systems our students need: systems of shared leadership, strategic risk-taking, and mutual responsibility. Systems of creative tension. Instead, we more commonly build top-down structures that generate destructive tension and bottom-up structures to avoid, relieve, or push back against them. At all levels and relationships, public education is replete with destructive tension. Whether it’s the policymaker focusing on test scores he has no control over, the School Board trying to improve classroom practice it has no experience with, or the district administrator trying to empower principals who have systematically been disempowered, we lack the structures and processes to support creative tension. So, our tension becomes destructive, structural stress, which becomes a self-fulfilling and redundant system of production. So, what are the key differences between a structure that produces destructive tension and one that generates creative tension? The following shows two possibilities for some relatively simply planning among school faculty to improve student outcomes. While this just illustrates the start of planning, the same models and considerations can be extended through all stages of action, reflection, assessment, and improvement.

Making a Plan: The Destructive Tension Approach A principal is approached by a group of teachers who are concerned about increased expectations to provide interventions and supports for students with intellectual disabilities, but without any additional planning time for new strategies. The principal listened to their concerns and then explained the rationale he used when making this decision. He assured them it was the right decision for their school. The principal recommended that the teachers use their current individual prep time to collaborate with other staff and develop individualized plans to meet students' needs. He asked to see their plans at the next staff meeting. Making a Plan: The Creative Tension Approach A principal is approached by a group of teachers who are concerned about increased expectations to provide interventions and supports for students with intellectual disabilities without additional time to develop and plan for the new strategies. The principal adds this topic to the agenda of a staff meeting scheduled for the next week. In that meeting, he asks staff to consider what each is doing in their classroom to ensure all learners have equitable access to instruction in meeting their individual needs. (Reflection) Through the discussion, the staff begins to recognize that too many learners are not finding success and that staff as a whole uses a fairly narrow range of interventions. (Ownership) Together with the principal, they agree on a shared goal to adopt a wider variety of interventions and supports to increase student success and identify the ones they want to focus on first. (Purpose) As part of this, they make a plan to have fellow teachers who are experts in the priority areas provide brief peer-to-peer professional development opportunities during each staff meeting. Over time, they aspire to have each teacher share their successes and challenges with the group. (Commitment, Teaching/Learning) The principal and staff develop a plan to allocate time for teachers to plan for implementation and engage a teacher coach to provide modeling and time to practice and refine their skills. (Collective Action) The principal and staff schedule regular, frequent opportunities to reflect and refine practice individually, with the coach, and in professional learning communities. (Reflection) To reduce the destructive tension that often undercuts efforts to improve how our schools function, intentional practices that nurture creative tension need to be imbedded throughout the relationships within the school and across a school system. Note: These relationships include not only adults, but also the young people as the largest stakeholder in public education. In their absence as a constituent in the variables of the creative tension model, we will never build structurally creative systems. Keep an eye out for our next blog to focus on creative tension among young people and adults. Written by: Anderson Williams, Teri Dary, and Terry Pickeral originally published by the Learning First Alliance  As we prepare to celebrate and reflect on the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington, I have been reading articles and seeing special reports on TV about the “I Have a Dream” speech. And, while I have heard most of it before in some form or another, things have struck me a bit differently this year. So the story goes: as Dr. King started to wrap up his remarks, he had delivered a solid speech (for him), which would undoubtedly make it the finest any of the rest of us might ever hope to deliver. But, there was a sense with him, and perhaps with others around him, that as he concluded his planned 4-minute speech, he hadn’t yet “nailed” it. And then Mahalia Jackson chimed in from his side: “Tell them about the dream, Martin.” Apparently, not once but twice, Mahalia urged: “Tell them about the dream, Martin.” Dreams are funny things. They can take us to distant places and liberate our minds and hearts. And yet, the dream untenable can trap us and leave us more hopeless and feeling more stuck in our current reality than ever. As Langston Hughes ruminated on a dream deferred: “Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode?” Dreams in reality can be as demoralizing as they are liberating. So, I have been reflecting on Dr. King’s dream to better understand the nature of dreams that become liberating:

It wasn’t that Dr. King had a dream; it’s that we did and he spoke it into being. He tapped into our collective experiences and timely sense of possibility and a pathway to change. He pulled the dream out of our hearts and minds and put it into our hands. Maybe for the sake of our families, schools, workplaces, and communities, we should all be better about sharing our dreams. Perhaps even more importantly, maybe we should all be like Mahalia Jackson urging others along: “Tell them about the dream.”  I had the pleasure of sitting and talking a few weeks ago with Bill Milliken. And, among the countless gems that began to flow when he started getting into the rhythm of the conversation, he dropped this: “If I am on an operating table, I don’t want collaborators. I want an integrated system!” With his sharp wit and wily twinkle in his eyes, Milliken is relentless in pushing us to “get it right” in our collective work for and with young people. This is what he has done and advocated for decades (it’s what makes him Bill Milliken!). His charm aside, I thought this quote was worth exploring a little further. So, I started thinking about the difference between collaboration and an integrated system. And, while there are certainly many specific differences to consider, I believe that, at its core, the difference is that of shared strategy (not to be confused merely with a shared strategic plan, strategic vision, strategic alignment, or any other narrow bastardizations of the concept of strategy). As collaborators, we typically bring 1 and 1 together and celebrate how we “strategically” made 2. To use another analogy, in collaboration, I have my puzzle piece and you have yours and we navigate around the edges a bit to see if we can “strategically” fit them together. But, collaboration is too often just that – around the edges – and generally happens downstream of our truly strategic organizational and institutional decisions. In other words, the critical decisions (who we serve, how, when, where, etc.) are already made by the time the collaboration tries to fit them together. Collaboration becomes a reactionary tactic attempting to overcome the lack of an actual integrated system! In an integrated system, we co-create in an ongoing manner our collective strategy, which guides and determines organizational and institutional decisions, key roles, responsibilities, and tactics. I work in this area or on this issue because it complements (not simply adds to) what you do and how you do it toward our common objective (also an element of strategy). An integrated system, therefore, requires constant communication, reflection, and learning so that together our 1 + 1 achieves the proverbial 3. Cynically, then, an integrated system comes at a cost: our work must actually be about our work, not just our organization or institution. Our work must be about the young person, for example, not whether or not I work in a school setting or an after-school setting. Let’s be honest, in most of our communities, the “systems of support” (or lack thereof) we have created for young people have been created because they work well for us as adults and the organizations we lead. Even in some of the best cases, our efforts represent an attempt to add things up for young people, but never really ask us to change what we are doing to make the system more complete. We generate plans of systems but claim expertise or blame funding for why someone else needs to change or do more, and not us. We rarely, if ever, achieve an integrated system at the level of shared strategy. We rarely, if ever, achieve the sort of integrated system that would actually work for our young people. Unfortunately, no amount of collaboration can overcome this reality. And, even more unfortunately, collaboration can obscure the weaknesses within the system by averaging them out. This, in turn, makes future efforts at a more integrated and strategic approach that much more complicated because we appear to be better than we actually are. It also makes it more difficult to identify and address where we are falling short. If I am on the operating table, I do hope my surgeon is part of an integrated system with the nurses and the doctor who diagnosed me. And, once there, I certainly hope the stellar work of my surgeon doesn’t obscure or average out the marginal work of my anesthesiologist! So, Bill, thanks for the analogy, the push to work smarter, and for ensuring the next time I have surgery that I will be completely scared-to-death! Over the last 10 years, I have seen countless nonprofit leaders (myself included) with after school programs, summer internships, leadership development trainings, and myriad other “opportunities” practically beg for student involvement, or just resign themselves to facilitating to half-empty rooms of teenagers. I have seen schools expand programming for “opportunities” like credit recovery, tutoring, mentoring, leadership, college nights, and many more, only to feel that their efforts were rebuked by disinterested students when no one showed up.

I have seen dozens of business leaders who wanted to share their expertise and their time to provide financial education, career orientation, job shadowing, mentorship and other “opportunities” become bewildered and ultimately driven away by the lack of apparent student interest. So, what’s the problem? Why don’t teens seize all of our “opportunities”? The most common adult response in my experience has been simply to blame the teen: You know how teens are! (Insert eye roll and/or deep sigh here along with shaking head.) But, unless we are really ready to disregard the vast majority of teenagers as apathetic do-nothings, we need to figure out a better response. We need to figure out our real “opportunity” gap – the gap between what matters and is engaging for teens and what we are actually offering. So, here are three A’s we can use to “stress test” our opportunities. These criteria might help us understand why some of our efforts have been successful and others not so much. Is the opportunity: 1. ACCESSIBLE Is the opportunity concrete and tangible? Executive decision-making around abstract future consequences, deferred gratification, or possible future opportunities is not in the teen brain biology. What does it mean to them now? Does its concreteness mesh with the self-concept of the teen? In other words, “opportunity” doesn’t necessarily mean “opportunity for me”. If I believe I’m not college material, then opportunities around college don’t really feel like opportunities, no matter how concrete they are. Is the opportunity communicated in terms that are relevant and relatable to students? “You need to eat your vegetables” is too often our model for communicating opportunities to teens. It doesn’t work. Our communications should help teens want to engage, not just tell them they should. Is the opportunity communicated in a medium that teens like and can easily access? Most of us have created posters no one sees, written school announcements no one hears, sent emails that no one reads, provided stacks of paper applications no one ever hears about, and on and on. We need to work with teens on a better communication strategy. We can do better. 2. ASPIRATIONAL Does the opportunity tap into something important to the teen? This is where we need to be better at including teen voice and leadership in the design of opportunities for teens. We can’t know what’s important to them without asking! Does it connect with something positive and forward looking – according to their standards and goals (and perhaps guided by ours as well)? Adults support teens by helping them generate goals and aspirations, but teens must own those goals if they are going to matter when they are faced with the choice between going to the mall or to tutoring. 3. ATTAINABLE Can it really happen and do they believe it? Depending on the opportunity, attainability can boil down to something as simple as access to transportation or as complex as overcoming cultural and social expectations. Regardless, the teen has to believe he really can make it happen. Is there a pathway and a personal plan? A plan and “my plan” are two very different things. “Your plan” for me is something altogether different again. There is no need to run ourselves ragged trying to get opportunities to students. Like any of us, they are seizing and rejecting opportunities all day, every day. If we want them to seize our opportunities, we need to start by making sure they pass the AAA test. If we want students to participate, we need to provide opportunities for them to participate.

If we want student voice, we need to create avenues to hear and capture it meaningfully. If we want students to be leaders, we need to be willing to step back and let them lead. Every day, adults use terms like voice, leadership, and engagement, and we design opportunities and programs based on them – but typically based on an indecipherable mash-up of what are unique and distinct concepts. Several years back, seeking clarity, I sat down in an attempt to organize and articulate some of these terms more fully. I ended up writing the Continuum of Youth Involvement. I wanted to help adults get on the same page about what we really want, what we are really willing to give up, and what we can gain when it comes to the meaningful involvement of our students/youth. After all, if we don’t know what we want from the start then we will continue to build programs and opportunities that don’t live up to our ill-defined aspirations (or perhaps surpass them in ways we are unprepared to see). If we don’t know what we are willing to give up as adults (power) then we will inevitably over-promise and under-deliver for the student in regard to their power. If we try to collaborate with youth and with other partners without clarifying our expectations, we will end up with little to show for our efforts. For example, I have seen countless schools, community groups, and citywide youth collaboratives who all said they were interested in “student voice”. So, they work for days or weeks or even months together around this idea only to find out that one person, or an entire group, just meant that they wanted to survey youth, another wanted focus groups and a youth on the “youth voice” committee, and yet another wanted students to have an ongoing and unfettered say on important issues in the school and community. After all that time and work, they realized they were never even close to being on the same page. Now what? Days, weeks, and months of work go down the tubes. Adults are frustrated. Youth are confused. Energy and resources are wasted. The efforts of the group often get documented in a wholly un-actionable set of ideas, plans, and programs and most everyone returns to business as usual. Worse yet, adults are less likely to invest in youth voice again (even through a better process) and students are less likely to trust adults when they hear that term. So, let’s commit to saying what we really want and are prepared to work for first. Let’s be honest about where we are and where we want to be along the Continuum of Youth Involvement. If we don’t have many students participating, let’s start there and not talk about engagement yet. If we aren’t sure how to develop meaningful leadership opportunities, let’s start by listening to students and get their “voice” on what is important to them. We can co-create leadership from there. If engagement feels too abstract, let’s work with students to facilitate real leadership, which done well, will spur deeper engagement. Before we can do what we say, we need to know what we are saying. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed