|

Wisdom isn’t inherent in our darkest days, but these days are our clearest path to it.

Perhaps it’s only in the darkness, or at least in the rationing of light, that we can come to appreciate it. Appreciate what it does for us. Appreciate what it makes of us. Appreciate what we are in it. Recognize what it does to others, what they do to it. Who creates it? Who consumes it? The darkness asks us different questions than the light. What does it feel like to be cold? To stay ever damp, the light never coming to dry or to offer warm reprieve? The cold and damp merging and wrapping us and dissolving us? What does it mean to be starved for light? To believe ourselves to be desperate and in need but still knowing the sun will proceed with its plan? No control. Fewer hours. Shorter days. How does gray feel? What are we supposed to do with it? It is a thing, this grayness. It cannot be ignored or explained with - or in contrast to - other colors. We must own it for what it is. What happens when life skins us of our perceived beauty, or our defenses, the leaves that sway and flicker and distract with their color and charm? What’s left? We are merely who we are. What do we do with that? What happens when we feel our bones? The deep ache of brokenness? That dull, radiating sense of being lost, exposed? Bare. These are not questions of death or desperation or darkness. This is life. This is winter. In winter, it is our ability to see what is, not what was, or what could be, or what should be that lets the light break through. The warmth. The growth. In the dark and barren and broken and matter-of-fact of the season, we may see more honestly the layers and cycles and phases of light, of life, of death, of time, of distance, of our place in it all. This is the brutal wisdom of winter.

2 Comments

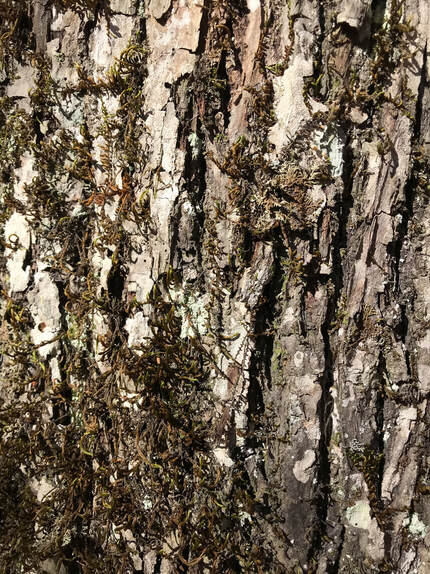

25 years ago, when I learned to paint and draw, the learning process had nothing to do with technique. In fact, by most people’s standards, it had little to do with painting and drawing at all – at least if I was doing it right. I was being taught to see. Once I could see, I could paint. And, while I don’t paint or draw at this point (someday again), I keep this lesson with me in every aspect of my life. To create, to find meaning, to communicate that meaning, I must be humble enough and patient enough and open enough and diligent enough to see myself and my world in its essence, to understand what it is offering and telling me – and then to create from there. I took a walk in the woods today, and everywhere I turned nature was asking me questions. It caught me off guard honestly. I just wanted to get out and get some exercise with the dog, but the woods wanted me to do more. They wanted me to see. To paint. A self-portrait. To be clear, I didn’t paint a thing – except in my mind. I tried to see what nature wanted me to see; myself, reflected in her. And, in her own constant changing with the wind and the water and the light and the seasons, she made it clear that my portrait was transient too. I am ever becoming a new self, seeing a new self, if I’m willing. So, here’s what she asked. 9 simple questions I should probably answer every day:  What color are you today? Color is a vibration. It is the perception of energy, wavelengths. So, what is yours today? Is it what you want it to be? How do others see it?  What colors do you surround yourself with? How do they blend or complement or contrast with your own? What frequencies do you absorb? What bounces off?  What’s your texture today? What coarseness is unavoidable at your age, given your life, experience? What strength can be created in the layers? What wisdom? What beauty?  What’s your light source? Where do you find your light? Do you run toward it? Look askance? Turn your back? The light is there and it’s bigger than you.  Where do you cast a shadow? How long is it? Is it getting bigger or smaller? Who is in it? What thrives in its cover? What fades or dies by it?  What’s your background? What past wraps you in stories without words? What blurs and fades? What defines your form? Your sense of shape?  How much space do you take up? Do you fill the empty space? How much positive space? How much negative? Are you the right size in your world, for your world?  What is in front of you? What lies beyond the canvas? What will you see in tomorrow’s portrait? And tomorrow’s tomorrow? Where you look determines what you will have the chance to see.  Do you accept the beauty? She didn’t ask where I find beauty or what I find beautiful. Its ever-presence was implied in her question. The question was whether and where and how I am willing to accept the gift.  Last weekend, I went hiking with my wife and daughters. We headed to a familiar trail knowing from previous hikes that the bridge was out where we needed to cross the river. But, we also knew that a couple of trees had fallen previously and created a very workable bridge that we’d successfully navigated before. But, as we approached, we realized those two big trees were no longer lying across the river. They were gone. It’s early Spring now and we weren’t planning on swimming and didn’t have any water shoes and the water was high and quite cold - but it was the beginning of the hike and we had to get across. Given that our trees were gone, the next obvious thing to look for were stepping stones - some pattern for us to get across without getting wet. No luck. So, then we walked up and down the bank a bit looking for options. And, low and behold, there was actually another fallen tree reaching all the way from bank to bank. The problem was that there was no way any of us had the balance to climb across it. That wouldn’t work either. Ultimately, we all shed our shoes and teamwork-ed it across the river - my kids were total troopers as we slipped and slid and stepped on rocks of all shapes and sharpness while our feet slowly transitioned from painfully cold to numb. It was not easy or particularly pleasant, my daughter hurt her ankle for starters as her foot slid deep between two rocks, but we crossed and continued on a wonderful hike (albeit with a bit of a limp) that included a picnic at a waterfall. On the way back, we approached that same crossing and that same skinny tree traversing the river - and a totally different idea came to mind. What if we didn’t try to walk on it but rather used it as a balance rail? After all, the rocks had been even more slick and more treacherous than we realized the first time. We’d still go barefoot but we’d at least have something to hold onto. As we mulled this option, we also noticed that the river bed was markedly smoother - pretty much one solid rock - at this small section beneath this tree. We shed our shoes and were across in no time - no slips, no falls, no ankle injuries. This all left me curious as to why we hadn’t seen this tree and this section of the river as the solution when we first faced the problem that day of crossing the river without a bridge. We had looked right at it! Here’s what I’ve come up with: 1. We initially doubled down on our problem-centric thinking. We needed to cross the river and the bridge was out, and now our familiar fallen-tree crossing was out too! We unconsciously processed this as two problems (1. Need to cross and 2. No trees) when really it was still the original problem and the absence of a previous solution. And, we unfortunately started solving for the absence of a previous solution: we needed a tree to walk across because that’s how we’d solved this before, but the one flimsy tree we saw just wasn’t going to cut it. 2. We jumped too quickly to a new solution without creatively adapting the resources we already had and knew. The tree was key to efficiently solving our problem all along - at least on this day - but when we couldn’t find one to walk across, we threw it out as part of the solution. We jumped quickly to the stepping stones strategy and then to the straight-up wading strategy without thinking creatively about how the tree could still be used in a different way to help us across the river. 3. We didn’t fully evaluate all of the variables and possibilities available with a new strategy. We knew the water was cold and we weren’t exactly excited about getting wet at the very beginning of the hike. But, once we believed that was the only option, we just made it happen. We looked at the depth of the water. We looked at the speed of the water. We knew about the cold of the water. We knew the rocks were slippery (not that slipper though!). We knew they could be sharp. But, we didn’t consider the alternative possibility of finding a smooth, solid rock floor that was just 30 feet from us - beneath that tree. Problems and solutions both build inertia, and sometimes this is critical for efficient and quick decision-making. But, sometimes this inertia sends us on the wrong path or on a more difficult path to the same spot or perhaps even derails us altogether (my daughter’s ankle could have been a lot worse) all because of the initial ease of not thinking much or the comforting familiarity with a known version of the problem and/or solution. So, if we can start recognizing and feeling inertia in our work and in our lives and committing to pausing just for a moment to take in the situation anew, to make sure we’ve thought of all of the variables, seen them fresh for today, and built our best options from there - rather than yesterday - we will find small moments each day that can transform how we create our way through life. I’ve already learned a lot halfway through Techstars, but the clearest and most obvious is: if you want to test your startup, go have a 100 conversations about it. I don’t mean that abstractly. I mean 100 actual, focused conversations.

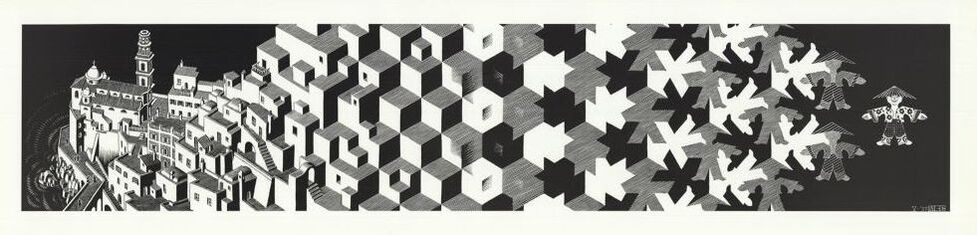

Go give your pitch 100 times and see if people get it. See what questions they ask. See what questions you start to ask yourself - as you stop focusing on crafting what you are saying so much that you can actually listen to yourself, and listen to them. Describe your product to someone who knows nothing about it. Describe it to someone who knows everything about it. Describe it to someone who is a user, knows a user, can’t imagine what it could possibly be used for. Describe your product 100 times. Describe your market to these same people. Describe your go-to-market. Describe all the things you know about how you are going to be successful 100 times and see at what conversation number you realize you actually don’t know that much. If you don’t get to that point, then there’s a good chance you are still talking more than you are listening. You may need more than 100 conversations. Describe your end user 100 times. See if you can describe the actual pain point that you solve for them. See if you can define why you are a must-have and not just a nice-to-have. See if you can convince others, or yourself, that someone will actually change their behavior to adopt your product. See how many times it takes before you don’t really even believe yourself anymore. At that point, you’re a lot closer to success. These 100 people aren’t “right”. In fact, they will contradict each other a lot. They will make the already difficult process of starting a company temporarily seem that much more difficult. So, why in the world would you do this to yourself? Because you’re not right either. And, the repetitions and iterations and brute force that talking to 100 people generates are your best start to getting there. M.C. Escher: Metamorphoses Image: https://images.app.goo.gl/nSMsrkBFAoniDFsF9 The question is not whether or not we are creative; it is whether or not we have found the right medium to express our creativity in a way that matters to the world. I have written before in my blogs and books about the idea of creative tension and how it can help us understand and diagnose the challenges and opportunities embedded in our relationships and work.

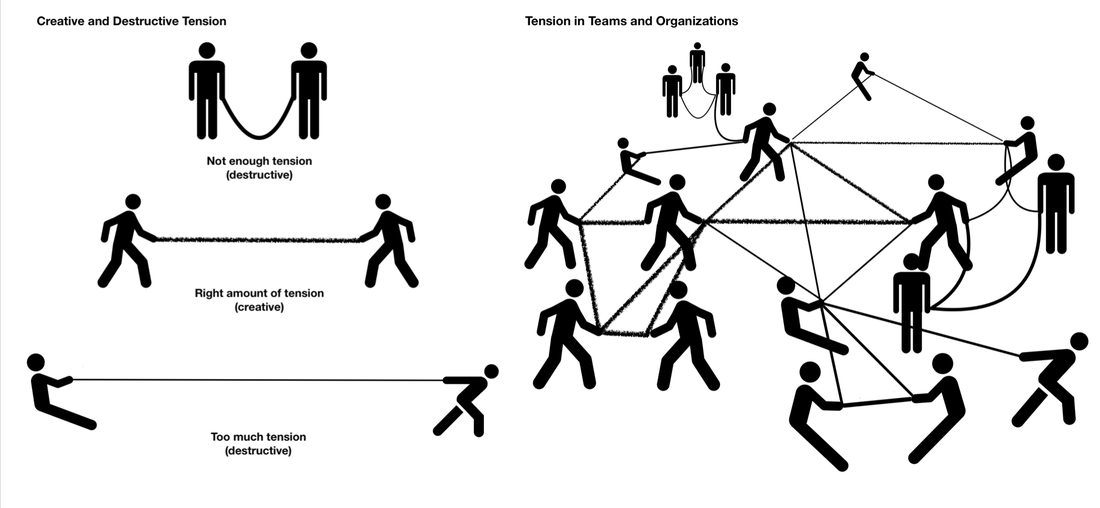

At the end of this week, I am stepping away from a team with whom I have worked for many years and with whom I have sustained a consistent, productive, and genuine creative tension. From a startup trying to take a mobile communication product into high schools to a pivot into healthcare, an acquisition by a healthcare company, and finally to an acquisition of that company by an even bigger healthcare company, we have worked and grown and learned and iterated together for the better part of six years. We all brought different skills and perspectives. Our ages varied. Our backgrounds varied. Our approaches to creativity and problem solving varied. Ultimately, however, we aligned around a set of principles that I now discuss as the elements of creative tension, but identified and learned largely through our work together. We didn’t know them and then practice them. We practiced them and came to know them. Shared Purpose: There is a common goal that necessitates working together to accomplish. Ownership: The collective owns the goal and understands various roles, responsibilities, skills, perspectives, and relationships needed to achieve the goal. Commitment: All parties commit not only to the process of working together but to their individual roles and responsibilities in the work. Teaching/Learning: Everyone is a teacher. Everyone is a learner. Collective Action: The act of working together creates tension that informs the evolving purpose and nature of the work as a whole. Reflection: The collective remains vigilant and reflective, as individuals and as a group, so that the tension remains creative and not destructive. Creative tension is a constantly changing dynamic of a relationship – a relationship between people and the work they are trying to accomplish together. For a visual, take a look at the images above and imagine yourself holding one end of the rubber band(s) with your colleague(s) holding the other. Sometimes, we are pulling the band(s) too tight. We introduce too much tension, reduce the flexibility of the rubber band, and introduce a fear that someone may drop their end and pop us with it, or even pull harder until it breaks. This is destructive tension caused by too much tension. Other times, we aren’t pulling much at all. The band is limp, without energy or possibility. This is destructive tension caused by an absence of tension. Creative tension is all about finding that right degree of tautness in the band where there is energy, and sound, and possibility, and the people holding it are relating positively and actively to each other and the band itself. The right amount creative tension is always changing, just as we and our work and our lives outside of work are always changing. As people change and as work changes, maintaining this creative tension requires constant vigilance – and as I have learned recently, simply may not always be maintainable. As I move on to a new startup, I feel the sincere loss of the creative tension of my team – although I look forward to helping build it with a new one. But, as our work and the organizations in which it has happened have evolved over the years, I found myself no longer able to generate the sense of purpose, ownership, and teaching/learning I needed to hold up my end of the rubber band, maintain my part of the creative tension. For me then, I feel a responsibility to move on. I genuinely believe that this is the creative act even as it comes with a significant sense of loss.  I was at a meeting recently where attendees were discussing innovation and how and where - and even whether - it should happen in large organizations. To innovate or not to innovate… As sides made their cases for and against, I offered a comment to the group that while we appeared to be presenting contradictory positions we actually agreed on the problems large organizations face in innovating. And, there wasn’t really any disagreement about whether they needed to. The difference in perspective was that one group saw the problems preventing innovation in large organizations as too big and too entrenched to solve and the other group thought they presented the perfect opportunity. In response to my assessment, someone commented: “Yeah, this group is the realists and that group is the idealists.” Everyone seemed to agree. And, I guess I didn’t immediately disagree, but it seemed way too simple, and it bothered me for some reason. For starters, I don’t like being put into an idealist box - which of course is where I was - simply because I believe human-created problems are solvable by humans. But, I let it go, and just started furiously taking notes on my phone about all the ways I felt that this seemingly simple comment presented a patently unhelpful view of innovation, organizations, and the world. Why do we attribute realism to the point-of-view that things cannot, will not, and perhaps even should not change? Why is that realistic in today’s world? Why do we attribute idealism - as the counter to realism - to people who believe things can and should change? In today’s world, isn’t that a lot more realistic? Isn’t it realism to know that change is inevitable? That innovation is necessary to keep learning, stay competitive, and to keep up with customers and markets? Is it really idealism to try and predict, invest in, and prepare for not just reacting to but leading that inevitable change? An idealist should be more than a dreamer, and idealism should never just be an excuse to pretend difficult problems are any less complex than they really are - or to deny that their solutions should be grounded in reality. Alternately, a realist shouldn’t passively accept that the current state is inevitable, and realism should never just be an excuse to lie prostrate in the face of difficult problems because, well, that’s just the way it is. Innovation is messy work and organizations are messy places. The most innovative organizations need idealistic realists mixing it up every day with realistic idealists. Anything that makes the people or the process sound any simpler may make innovation easier to talk about but can also make it a lot more difficult to achieve.  There are five key relationships that every creator needs to thrive. While these aren’t always a one-to-one match (i.e. one person, one relationship), they represent key inputs and a continuum of perspectives we all need to support, guide, and grow our creative practice. 1. Supporter Our supporters are the people whose primary investment is in us as people. Their support is unconditional. In other words, they support us whether our creative process, whatever it may be, is deemed successful or not. They keep us working when we have lost faith in ourselves. 2. Collaborator Our collaborators are those who get into the creative mix with us. This can mean literally getting their hands dirty with us, or diving in to challenge us intellectually. Our collaborators are also creators and their creative process and outcomes are directly tied to our own. 3. Critical Friend Our critical friends are deeply trusted peers. They can also be collaborators, but they often work in parallel, not directly with us. These are the people who see our work and our process most wholly and ask us the most challenging questions that push and refine our work. A critical friend could be a very different thinker or work in a different medium or discipline than we do. 4. Promoter At some point, our creative output needs to meet a market or a consumer of some sort. Our supporters, collaborators, and critical friends may tell their friends about us. Our promoters tell everyone who will listen. They step up and are bought into our creative output sufficiently to put their own name on it as an endorsement. Promoters can be developed organically, or perhaps even hired, depending on the creative context. 5. Respected Critic/Doubter This one may be less intuitive, but our critics tap a different motivation than any of the other relationships here. They may even spur spite, indignation, and a desire to prove them wrong. These may seem odd things to want in our creative lives, but they have the potential to make us better creators. So, these are not the critics we dismiss simply because we think they don’t like us. These are people whose doubt of us matters to us in some way. In fact, it can even work if we are our own biggest critic/doubter as long as that motivates us rather than neutralizes our creativity.  I love this question, and I believe starting with it can open a world of possibility around addressing the most pressing issues, big and small, personal and public, work and life that we face each day. Here are some thoughts on how to release its implicit power: HOW Assume possibility. If we genuinely and openly explore “how,” we have the opportunity to both better understand the problem we are facing and to open the door to new solutions. We have to start from a place of faith and confidence in possibility. In turn, solution thinking done well also asks us to think critically about the rules and norms of the problem, the structure. We must analyze and understand better how we arrived at the present to deepen our understanding of how we might address it, not just incrementally, but substantively in the future. Focus on strategy. To identify “how” substantively, we need to think strategically. When we try to solve problems by starting with what we should “do” then we miss the opportunity to transform the condition that generated the problem in the first place. We end up doing stuff that just gets us to the next iteration of the same problem. Strategy focuses on systems and structures and relationships that we must invest in in order to implement our transformative “how” more consistently, sustainably, and transformationally. Align tactics. Clearly, at some point, we must “do” something. We just shouldn’t start there because our tactics are often rooted in the skills and perspectives and practices we are most familiar with, the ways we already “do.” It doesn’t take a big leap of logic to see that those ways aren’t going to be sufficient for transforming our problem. In fact, they may be part of it. While our existing skills, perspectives, and practices may be reinvested in or reorganized for incremental improvements, to transform conditions our tactics have to be rethought and reconsidered to align directly with our strategies. We need to “do” things differently, and to make that happen we will probably also need some new skills, perspectives, and practices in the mix. MIGHT Question creatively. Genuine belief in possibility begs us to be more creative. Creativity that can support the vastness of possibility starts with a willingness to question everything. This questioning isn’t about throwing out everything and starting over. In fact, it allows us the opportunity to identify and strengthen the core beliefs, the foundations upon which our work and relationships are built, the things we can’t and won’t change. At the same time, deep, creative questioning does allow us to identify ancillary assumptions about “how we do things” that, in fact, are just a matter of bad habit, culture, or climate issues. They might even live only at the small group or even individual levels of our organization or work but deeply impact our ability to accomplish our goals. Generate lots of solutions: Similar to our urgent need to “do” something, when we start generating solutions, we often have an urgent need to get to the “right” one as quickly as possible. Getting to the right answer, however, usually requires some combination of multiple creative answers. So, we need to generate a lot of possible answers, and some that even seem impossible, before we start whittling things down. The pressure of generating a volume of ideas (in the next five minutes brainstorm some ideas vs. in the next five minutes come up with 20 ideas) forces us to move our thinking beyond our normal parameters. We force ourselves to come up with outlandish ideas – which may just hold the nugget of wisdom that triggers the ultimate solution. It also just generally gets us out of our cognitive lane and frees our thinking. Iterate. As we start to focus our creative ideas and narrow them down, we need to stay aware of when and how we start to get wedded to them and start building assumptions around them. As we feel that human need to get to the answer, we can inadvertently make the jump to what we believe it is and derail the creative process. We must remain open and flexible and continue to iterate on ideas rather than just carry them forward. In other words, we have to keep learning. Have we uncovered some new truth that changes our assumptions? Have we identified alternative strategies and tactics and are we staying open to those as they come? What are their implications on our previous strategies or tactics? Basically, we have to remain committed to creatively questioning throughout the process. WE Engage diverse voices and ideas. To support the generation of lots of solutions, we should also engage diverse voices and perspectives. Generating a lot of the same kind of ideas from the same perspectives doesn’t get us anywhere. But, when we stop and engage stakeholders, and even non-stakeholders, in the ideation process, we generate more raw material to work with, and often material we never thought about, blinded by our own perspectives. Develop shared purpose. Even though it is the last word in the question, solving for “how might we” starts with the idea of “we.” It’s the subject. It’s collective. We work with and through others. To solve the problems we need to solve and create the future we want to create, we must share a sense of purpose of what we are trying to accomplish. None of the other parts of this process will work fluidly if our purposes are not aligned. The process of creating is hard enough without facing the constant and unnamable stress and frustration of inadvertently working at cross-purposes. This is perhaps the most critical investment a leader can make. Share responsibility and accountability. When we are trying to transform our work and/or the world, we must not just share purpose but ownership. “We” works at all levels of our creative process and related attempts at implementing new strategies and tactics. So, we must be intentional over time as we continue to ideate, iterate, and implement any change efforts, so that a sense of the collective remains. We will divvy up specific responsibilities, different people deploy different tactics, but we should continue to share accountability for achieving our strategy, driving toward our shared purpose throughout the creative process. Image: https://beingenpointe.com/2011/09/ |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed