|

It can be hard transitioning to manager. It totally shifts the mindset and value-creation principles that so many new managers developed, delivered, and were recognized for in being promoted to manager. The shift isn’t just one of roles. In many ways, it can feel like one of identity. The people we promote to manager typically value what they do, and value the impact what they do has had on the company.

When we promote them to manager, we recognize them for what they have done, but we change what they do. We change how they are expected to add value and have impact. And yet, we rarely slow down to help reframe what it means to be a manager and how that’s different from the work they’ve done to get there. I was having this exact conversation with a new manager when it dawned on me that she was actually expressing a sense of loss in becoming a manager. She felt less impactful in this role, less valuable for “passing off” work to someone else that she had always done herself. So, in some attempt to hold onto her historic value, she kept doing what she’d always done - and just layered her new management duties on top. She was burning herself out, her team was flailing, and she was even considering leaving the company. This is a person who had recently been promoted because of her indefatigable energy and commitment to the company! They love her. She loves them! For nearly a decade, she has found life-purpose and meaning in her work there. She is proud to have helped build the company, to have been there to grind it out with the founders and just make stuff happen for their customers. In other words, she knows how to deliver value and how to feel valuable as a hard-working, dedicated, individual contributor. Now, she’s a struggling manager. It dawned on me that to reboot this transition to manager, she has to redefine her value creation equation – from an equation where she creates direct value to one in which she also creates value through others. I explained somewhat off-the-cuff that as an individual contributor, she delivered one unit of value with one unit of work. As a manager, when she enables one of her people to execute on that unit of work, she creates one unit of value out of the fact that it was executed and another unit of value out of the fact that someone else did it. In other words, as a manager, she is creating more value, not less, when someone else does the work and does it successfully. She looked at me puzzled for a moment, and then a sort of liberated smile flashed across her face. “That’s it!” She exclaimed. “I never thought of it that way. But, that’s it. I know I can’t keep doing what I’m doing. My supervisor has been pushing me that it’s not just about me delivering the work. It’s about the team. I’ve got a great team. I know they want more from me. They want to grow. I’ve just been thinking about it wrong.” So, here’s the simple math: Individual Contributor Value = Work Execution Manager Value = Work Execution + Capacity Building Work Execution Variable:

Questions for a new manager to ask yourself:

0 Comments

Having difficult conversations is…well…difficult. This is especially true if you need to have a difficult conversation with a supervisor or someone else at a higher level in your organization.

I was recently coaching a young executive who had been struggling with a direct report, who had a history of creating challenges among the team even back to a previous manager. But, this person was also highly valuable because of their skills and experience, and no one wanted to lose them. The young executive with whom I was speaking had sought advice and support from his superior to deal with the issue. In an attempt to help, his boss said that the problem employee could just report directly to him and he would deal with it. Even with the best intentions and that positive sense of collective required in the hustle of a startup, this attempt to help created far bigger problems for the young executive. Now, the rest of his direct reports believed that if they disagreed with him or if they didn’t like what he said then they too could go around him and directly to his superior. The workaround intended to relieve this young executive had accidentally neutered his ability to lead the rest of his team and as a result multiplied his stress. We were talking through how he might have this conversation with his boss. Sparing additional detail, here were some key principles we landed on: Approach with gratitude: We talked about how he could acknowledge the good intent of his supervisor’s move and open the conversation with that appreciation. This would ensure that nothing came across as complaining or personal or ungrateful, which were things he was really worried about. He valued and wanted to protect his positive relationship with his boss. Appeal to common interests: This young executive was hired because of his own skills and the belief that he could lead this team and the company to a new phase of growth and maturity. He knew that he and his boss could agree on this premise. With that out in the open, he needed to describe the unintended consequences of changing the reporting structure. Clearly, neither of them wanted this young executive to not be able to perform the job he was hired to do. Focus on outcomes, not people: We talked about making sure the conversation with his boss never became about the valuable, but problem employee. It couldn’t become personal. It had to be about process and performance. So, this young executive needed to show with examples how his leadership was being undermined with other direct reports and how that was impacting performance. Define an agreeable path forward: This was not a situation that could linger. This young executive was losing authority and credibility by the day and as a result was also developing a lot of frustration and anxiety about his role and the work and so forth. So, he needed to use steps 1-3 to make sure the conversation was primed for: so what do we do now? Within a few hours of our conversation, I got an email back. The young executive and his boss had agreed that an announcement would be made to the team about the change in reporting structure, so it no longer looked like a workaround that others could also take. They also defined specifically when that announcement would be made. This path forward not only would help solve the authority problem but would also relieve the stress valve for the young executive who now knew something would happen. This wouldn’t linger. Perhaps most importantly in the long run, I suspect that this young executive’s approach and willingness to have a difficult conversation with his boss only reinforced why he was hired in the first place. I have a feeling his opportunity and authority will only grow as a result of the experience. A leadership team I support was struggling with a particular employee and the issues had been lingering for several months. This employee had been a positive team member and quality contributor until recently. But lately, the employee’s performance simply hadn’t been good enough. The quality wasn’t there. Her work was often incomplete. It lacked depth and insight. And, it was starting to impact the team as the other members had picked up the slack and, as a result, was feeling the tension with management.

The management team had already let the employee know improvement was necessary. They had started to meet more frequently and to dial up the necessary feedback and micromanagement. But, the more time they spent together, the more the employee seemed to pull back. In other words, as they ratcheted up their formal communication to try to course correct, the informal and discretionary communication all but stopped. The managers didn’t want to fire her, but they didn’t know what else to do. They felt stuck. In a session with one of the managers, we discussed the simple-but-powerful 5 Whys process created decades ago by Toyota to help them drill down to root causes of problems in their manufacturing. The process is so simple, however, that it really works with any problem. Just ask “why” five times, each time asking “why” of the previous answer such that you create a sort of cascade of deeper and deeper problem statements. If nothing else, it can deepen your understanding of the variance and dynamics of a problem to know what part you have the time, energy, and resources to address. In other words, you may not always have the capacity to address the root cause but at least understand that you aren’t addressing the root cause. In this case, the manager took the 5 Whys back to her colleague and they agreed to use it as a structured conversation guide in a meeting with their struggling employee. They introduced the process and the three of them worked together to dig deeper into what was behind the employee’s poor performance. This was the manager’s message back to me: “I tried the 5 Whys in my conversation with this person. My boss was with me as well. So, I just introduced the process and put {the performance problem} up on a whiteboard and started asking why. It was so helpful keeping the conversation focused and not so emotional. And after all of this time where we thought the employee was the problem, we discovered she actually didn’t have all the information she needed to do what we had been asking her to do. It was us! It was our problem! And here we were thinking we were going to have to fire her! Anyway, we left the conversation so much clearer and in a much better place. It was great! Thank you!” I was on a recent coaching call where a mid-level leader of an independent business unit within a rapidly growing company was dealing with the following realities:

1. Her team was entirely remote. 2. She was entirely remote from her supervisor and company leadership. 3. Her team was acquired over two years prior but still felt little connection with the acquiring company. She and her team were performing and performing well, but without much distinction from how they worked prior to the acquisition. The autonomy was good on some levels, but the challenge for this leader was that she was being asked questions about the larger organization, its vision and direction, and even what would happen when it exited. She didn’t have any of the answers. She felt as disconnected and uninformed as they did. There was a slow but growing sense of fear and uncertainty within her team and a developing anxiety within her as their leader. So, what should she do about it? How should she present her concerns? Here are some things we came up with: 1. Start with you. We talked about her just having some open conversations with her manager and/or peers at similar levels or situations within the organization as a way of asking how others were managing this better than her. Instead of looking up at the organization and starting with “you need to fix this”, this approach takes ownership and starts with “how can I do better”. No one is going to shut you down, marginalize your concerns, or get defensive when you start with “how can I do my job better?” 2. Speak on behalf of your team. As you explore how you can do better, frame it with what you are hearing from your people. Share their stories. Share the questions they are asking you that you can’t answer. Give a sense of their fear and frustration. Paint that picture. Then, frame your needs as it relates to your ability to effectively lead them. If you don’t feel informed and connected, you can’t help them feel informed and connected. So again, you are asking to be better equipped to do your job well – which everyone should be pretty well in favor of. 3. Show you are thinking big picture. Provide your supervisor the strategic context for your concern. Talk about the health of the team and the related health of the company. Talk about company growth and the challenges of retaining and attracting talent. Talk about the cost of losing some of the specific people who are asking you the questions you can’t answer. Talk about how this problem only gets bigger the more the company grows if it’s not addressed. 4. Listen for how others see, understand, and prioritize the issue. You don’t have to jump straight to solutions. In this case, the first goal is to raise the issue and get a conversation started. So, in alignment with #1, stay focused on tactical next steps and where they can start with you, but involve others where necessary. Rapidly growing companies have innumerable competing priorities. Raise your issue and better understand where it fits in the mix. This will help align expectations for action or lack thereof. Working with remote teams requires an entirely different level of intentionality when it comes to communication and culture. Problems like the one this leader was presenting don’t naturally get seen by company leadership and don’t organically surface in their day-to-day. Leaders in these situations must recognize this reality and find ways and forums for bringing these issues to light. They can’t just let them stay quiet. That’s clearly not in anyone’s best interest. Sometimes it’s hard to find the words or the process where none seem to exist. But, that doesn’t make conversations like these any less imperative. In order to effectively lead through others, you often have to manage up to get what you need. I spend a lot of time with individuals and teams working on two big concepts: trust and communication. I always tell them: if trust is the foundation of leadership then communication is the medium.

And yet, I have had several occasions recently where more senior leaders have heard about these topics and figure the discussions and trainings must be for junior leaders. They are so basic! I would caution here not to confuse basic with foundational. As every architect knows, you can’t build anything without investing in, improving, and innovating at the foundation. Every foundation must be designed based on the needs of the structure, the current standards, the environment, new technologies and materials. No single foundation suits all buildings – or all relationships. PWC recently published their Trust Survey results for 2023 and they suggest that leaders across industries are underinvesting in their trust foundation – and their people feel it. Here are a few highlights from their research:

It’s also worth noting that 91% of business executives say that their ability to build and maintain trust improves the bottom line. Every human being who has ever had a relationship with another human being knows that trust is far easier to break than to build, much less rebuild. And, it’s hard to build a relationship much less a scalable company without due attention to its foundation. Here are a few tips for checking your foundation: 1. Emphasize the Why: Make sure everyone understands why the company exists and help them find meaning in working there. Help them find their personal "why" in the work regardless of their age, role, or level in the company. Meaning helps us keep a bigger perspective on our work and our relationships and keeps the little things from being trust breakers. 2. Share Values Stories: Trust is built over time and the more you build the more grace you get when a trust-breaking event happens. Your company stories are your “grace bank” that help you build a track record of living your values so that when it appears you had a miss, people see and understand that as the outlier not the norm. 3. Communicate Constantly: Another one of my refrains is that “silence is never silence” in a company. In the absence of your voice, the voice of the company, your people will make up their own stories about you and it – and they are likely to be worse than reality. 4. Own Your Mistakes: Making mistakes does far less damage to trust than not owning those mistakes. You make mistakes. Companies make mistakes. The trust impact comes down to how you handle that reality rather than deny it.  As an artist, when you learn to paint with oil paint, for example, you have to learn the characteristics of the paint, how to thin it, how to thicken it, how to build a surface, how to mix color, how to manage your brushes and the nuances of the surface of a canvas or board or whatever you are painting on. Knowing these foundations of the medium is what enables you to use the medium for your unique expression. Things will likely be messy, muddled, and frustrating at first, but putting in the time with the mess is the only way to become an artist. Leadership is the same. You have to learn the characteristics of leadership, how to communicate, how to empathize, how to listen, how to delegate, how to prioritize, how to know when to step up and when to step back to empower others. Knowing these foundations to leadership is what enables you to find your unique version of it. Things will likely be messy, muddled, and frustrating at first, but putting in the time with the mess is the only way to become a leader. In art or leadership, there is no prescription for the outcome, there is only knowledge and application of the medium and investment in the process. So, artist, leader, or both, you have to be willing to get a little messy in your practice if you are going to find your voice.  Last weekend, I went hiking with my wife and daughters. We headed to a familiar trail knowing from previous hikes that the bridge was out where we needed to cross the river. But, we also knew that a couple of trees had fallen previously and created a very workable bridge that we’d successfully navigated before. But, as we approached, we realized those two big trees were no longer lying across the river. They were gone. It’s early Spring now and we weren’t planning on swimming and didn’t have any water shoes and the water was high and quite cold - but it was the beginning of the hike and we had to get across. Given that our trees were gone, the next obvious thing to look for were stepping stones - some pattern for us to get across without getting wet. No luck. So, then we walked up and down the bank a bit looking for options. And, low and behold, there was actually another fallen tree reaching all the way from bank to bank. The problem was that there was no way any of us had the balance to climb across it. That wouldn’t work either. Ultimately, we all shed our shoes and teamwork-ed it across the river - my kids were total troopers as we slipped and slid and stepped on rocks of all shapes and sharpness while our feet slowly transitioned from painfully cold to numb. It was not easy or particularly pleasant, my daughter hurt her ankle for starters as her foot slid deep between two rocks, but we crossed and continued on a wonderful hike (albeit with a bit of a limp) that included a picnic at a waterfall. On the way back, we approached that same crossing and that same skinny tree traversing the river - and a totally different idea came to mind. What if we didn’t try to walk on it but rather used it as a balance rail? After all, the rocks had been even more slick and more treacherous than we realized the first time. We’d still go barefoot but we’d at least have something to hold onto. As we mulled this option, we also noticed that the river bed was markedly smoother - pretty much one solid rock - at this small section beneath this tree. We shed our shoes and were across in no time - no slips, no falls, no ankle injuries. This all left me curious as to why we hadn’t seen this tree and this section of the river as the solution when we first faced the problem that day of crossing the river without a bridge. We had looked right at it! Here’s what I’ve come up with: 1. We initially doubled down on our problem-centric thinking. We needed to cross the river and the bridge was out, and now our familiar fallen-tree crossing was out too! We unconsciously processed this as two problems (1. Need to cross and 2. No trees) when really it was still the original problem and the absence of a previous solution. And, we unfortunately started solving for the absence of a previous solution: we needed a tree to walk across because that’s how we’d solved this before, but the one flimsy tree we saw just wasn’t going to cut it. 2. We jumped too quickly to a new solution without creatively adapting the resources we already had and knew. The tree was key to efficiently solving our problem all along - at least on this day - but when we couldn’t find one to walk across, we threw it out as part of the solution. We jumped quickly to the stepping stones strategy and then to the straight-up wading strategy without thinking creatively about how the tree could still be used in a different way to help us across the river. 3. We didn’t fully evaluate all of the variables and possibilities available with a new strategy. We knew the water was cold and we weren’t exactly excited about getting wet at the very beginning of the hike. But, once we believed that was the only option, we just made it happen. We looked at the depth of the water. We looked at the speed of the water. We knew about the cold of the water. We knew the rocks were slippery (not that slipper though!). We knew they could be sharp. But, we didn’t consider the alternative possibility of finding a smooth, solid rock floor that was just 30 feet from us - beneath that tree. Problems and solutions both build inertia, and sometimes this is critical for efficient and quick decision-making. But, sometimes this inertia sends us on the wrong path or on a more difficult path to the same spot or perhaps even derails us altogether (my daughter’s ankle could have been a lot worse) all because of the initial ease of not thinking much or the comforting familiarity with a known version of the problem and/or solution. So, if we can start recognizing and feeling inertia in our work and in our lives and committing to pausing just for a moment to take in the situation anew, to make sure we’ve thought of all of the variables, seen them fresh for today, and built our best options from there - rather than yesterday - we will find small moments each day that can transform how we create our way through life. A couple of years ago, I was working with a multi-billion dollar, global financial services company that had (pre-Covid) a vast network of on-location staff as well as remote online and call center staff to provide direct support to their customers. As we talked about growth and change in their company and their market, we explored if and how they were, or could be, learning from these front-line employees spread across the globe. What were these people hearing directly from customers that the company really needed to hear and understand?

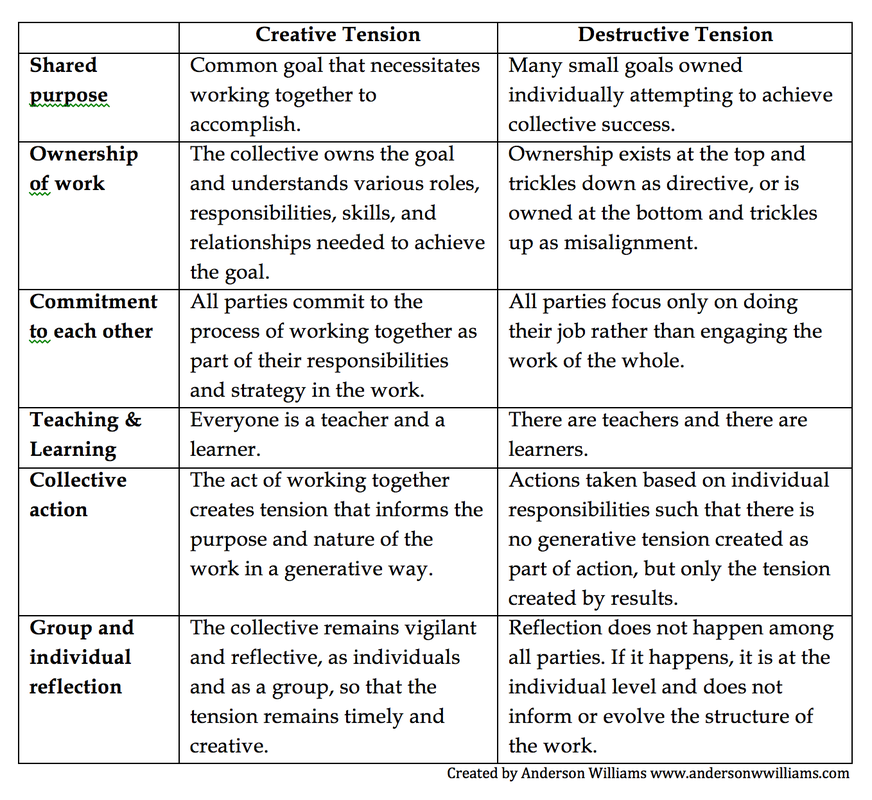

We’ve all heard the saying about the importance of having “an ear to the ground” so we can sense imminent changes in our work environments and markets, but how well do we do it? Who has their ears to the ground more than those meeting our customers where they are? Dealing with their problems? Frustrations? Who has the potential to positively or negatively impact our customers minute-to-minute on a daily basis? Too many of the people on the front-lines of our work think they are too “low on the totem pole” to speak up in our companies or don’t have the power to create change in their own work. And, too many companies think the same way. As a result, many of us are really missing the opportunity to become more resilient, adaptable, and creative organizations. When we don’t listen to our customers and the employees who interact directly with them, we run the risk of missing indicators of emergent change in our markets, products, and even broader society that can lead our products and companies toward their next iteration. Through a simple, facilitated reflection process, this company - which thought it did a good job listening to its people because they could reel off some good anecdotes - realized that their listening to front-line employees across the organization was far spottier than they would like. They recognized that their anecdotes were about specific leaders or departments that carried this value of active listening rather than a reflection of a systemic approach or strategy by the firm. The implications from this kind of company self-awareness became pretty vast as they then considered who they needed to train, how they needed to adjust professional roles and expectations, and how a better process of listening could improve their product offerings. To cultivate a powerful culture, people at all levels of our companies need formal and informal outlets to provide feedback, ask questions, and share ideas and solutions. This is just strategically smart. It’s not about being nice to our employees. Not only will listening to our employees make our company more resilient and adaptive, it will also make for happier employees and better products and services for our customers. When they know their ideas and insights are respected (even if not always acted upon), our people will more actively and critically identify customer patterns and frequent issues that we may never see, and solve them in ways we may never have thought of. They will own their work and the whole company will perform better because of it. Powerful cultures don’t happen by accident. They result from powerful leaders, powerful relationships, and organizations that understand and leverage the power of their people at all levels. Also relevant: “Does your organization have a powerful culture or a culture of power?”  In my last blog "Stop doing your part", I focused on building a do-what-it takes team. But, consider this the appended warning to that blog: you can’t just ask people to do what it takes as an excuse for not investing sufficiently in your strategy or improving your own leadership. So, as much as we want the do-what-it-takes attitude and we understand and celebrate the successes that such an attitude can generate, we need to check ourselves to make sure we aren’t burning people out. Just because one of our people can step up and do extraordinary work in a difficult situation doesn’t mean we should allow that situation to persist - or chronically resurface. Their extraordinary work should not become the ordinary expectation. Extraordinary individual effort is no more sustainable for driving successful teams over time than the do-my-part mentality that I discussed in the last blog. It leads to burnout and pushes our do-what-it-takes people to feel they are just being taken advantage of. It doesn’t take long for people to realize when they get recognized for doing great work simply by getting more work. So, we must think critically about why we find ourselves in situations that require extraordinary effort from our people. Is it strategy? Resourcing? Skills/team/work mismatches? Unreasonable expectations? Or, is our leadership perhaps fomenting unnecessarily harried working conditions? It is probably some of all of these as they tend to be interrelated. So, let’s celebrate our people for doing what it takes but build teams and organizations that aren’t always pushing them to the limit.  And start doing what it takes. Teams are complex social systems with emergent dynamics among members and emergent contexts in which they operate. This is true of small teams and only more so as teams grow. If people merely do their part, they are actually complicating things, forming a complicated system; and complicated systems are to complex work what the assembly line is to internet security. In dynamic and growth-oriented work environments, your “part” is always emerging, so as soon as you start just doing it then you probably aren’t fully doing it anymore. While you may be a high performer and may be surrounded by high performers, no mere collection of individual contributors will ever manifest in a sustainable, high-performing team doing complex work. A set of powerful parts will not inevitably make a powerful whole. In fact, the opposite is more likely true: the more powerful and simultaneously partitioned the individual contributors the less likely you are to build a powerful team that bridges them. The strength of the individual contributor mindset is too strong; the rationalization of the do-my-part mentality feeds itself and invites others to just do their part as well. As a result, as do-my-part teams grow, they become increasingly less adaptive and less effective in responding to the emergent dynamics within and around them. So, how do we build more complex teams and avoid complicated ones? How do we inspire more people to do what it takes? Hire for where you are going, not just where you are. We often think about hiring for “fit” with our team and/or organization. While this may seem to make sense in the immediate term, we should understand that “fit” is a temporary construct that belies the change inherent in a growth strategy. So, fit today could easily not fit the future. Consequently, we should hire and invest in people who will help us deliver and define an emergent future. We need team players and learners who will not just do the work but will help create and define it. Communicate the vision. If our people at all levels are going to do what it takes to define our collective future, they must be organized around and feel a sense of ownership of some collective vision. They should also understand (and it should be true) that they are helping define how that vision evolves as the team and market context also evolve. Team leaders need to communicate and actively invite input on the vision not merely to try to get our people aligned around it but to more quickly identify the people who don’t, and perhaps won’t ever, own it. Promote creative tension. I have written about creative tension in both of my books as I continue to try and flesh out my thinking on team power dynamics. For this blog, I’ll just share below the core components of relational tension and illustrate how they differ in environments of creative versus destructive tension. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed