|

The question is not whether or not we are creative; it is whether or not we have found the right medium to express our creativity in a way that matters to the world.

1 Comment

I have written before in my blogs and books about the idea of creative tension and how it can help us understand and diagnose the challenges and opportunities embedded in our relationships and work.

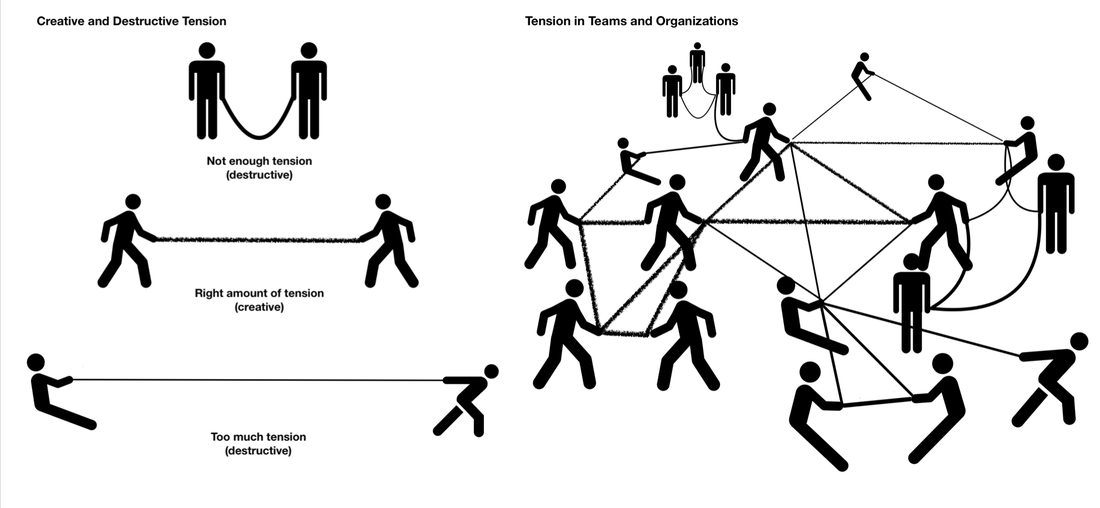

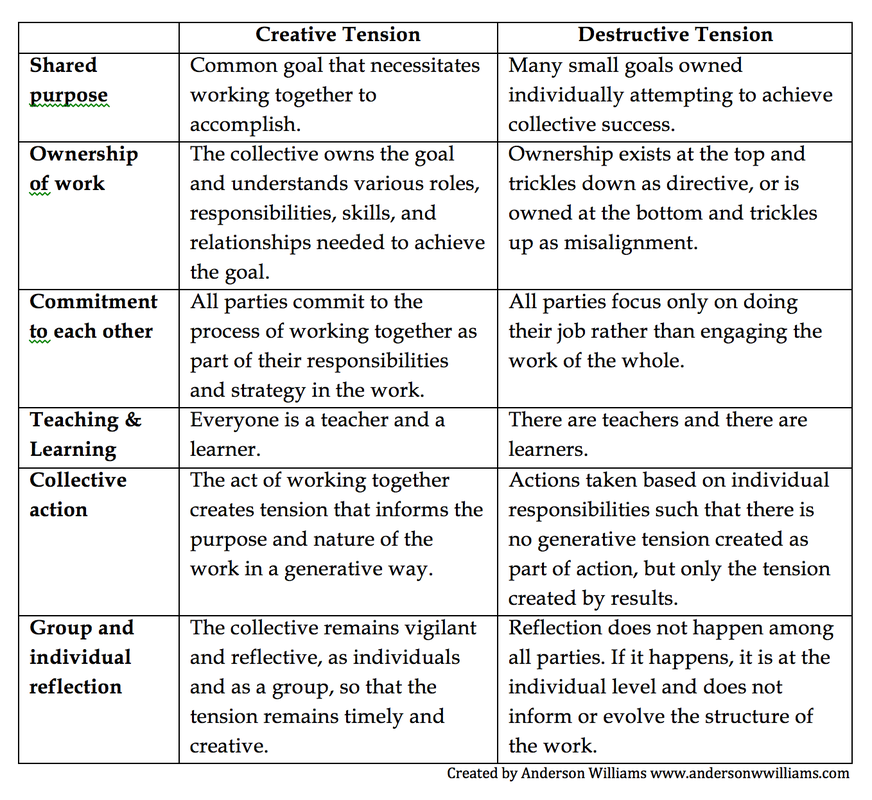

At the end of this week, I am stepping away from a team with whom I have worked for many years and with whom I have sustained a consistent, productive, and genuine creative tension. From a startup trying to take a mobile communication product into high schools to a pivot into healthcare, an acquisition by a healthcare company, and finally to an acquisition of that company by an even bigger healthcare company, we have worked and grown and learned and iterated together for the better part of six years. We all brought different skills and perspectives. Our ages varied. Our backgrounds varied. Our approaches to creativity and problem solving varied. Ultimately, however, we aligned around a set of principles that I now discuss as the elements of creative tension, but identified and learned largely through our work together. We didn’t know them and then practice them. We practiced them and came to know them. Shared Purpose: There is a common goal that necessitates working together to accomplish. Ownership: The collective owns the goal and understands various roles, responsibilities, skills, perspectives, and relationships needed to achieve the goal. Commitment: All parties commit not only to the process of working together but to their individual roles and responsibilities in the work. Teaching/Learning: Everyone is a teacher. Everyone is a learner. Collective Action: The act of working together creates tension that informs the evolving purpose and nature of the work as a whole. Reflection: The collective remains vigilant and reflective, as individuals and as a group, so that the tension remains creative and not destructive. Creative tension is a constantly changing dynamic of a relationship – a relationship between people and the work they are trying to accomplish together. For a visual, take a look at the images above and imagine yourself holding one end of the rubber band(s) with your colleague(s) holding the other. Sometimes, we are pulling the band(s) too tight. We introduce too much tension, reduce the flexibility of the rubber band, and introduce a fear that someone may drop their end and pop us with it, or even pull harder until it breaks. This is destructive tension caused by too much tension. Other times, we aren’t pulling much at all. The band is limp, without energy or possibility. This is destructive tension caused by an absence of tension. Creative tension is all about finding that right degree of tautness in the band where there is energy, and sound, and possibility, and the people holding it are relating positively and actively to each other and the band itself. The right amount creative tension is always changing, just as we and our work and our lives outside of work are always changing. As people change and as work changes, maintaining this creative tension requires constant vigilance – and as I have learned recently, simply may not always be maintainable. As I move on to a new startup, I feel the sincere loss of the creative tension of my team – although I look forward to helping build it with a new one. But, as our work and the organizations in which it has happened have evolved over the years, I found myself no longer able to generate the sense of purpose, ownership, and teaching/learning I needed to hold up my end of the rubber band, maintain my part of the creative tension. For me then, I feel a responsibility to move on. I genuinely believe that this is the creative act even as it comes with a significant sense of loss.  1. Fall in love with your idea. Creative people generate lots of ideas. We love ideas. They excite and invigorate us. The ones we love the most can easily start to feel like a part of who we are, and they can even express the ways we want to relate to the world and the world to us. But, when it comes to actually relating to the world, our ideas are almost certainly wrong. They aren’t all wrong – they are just some wrong. And, if we are going to turn them into products that people want to use, we can’t afford to start thinking our ideas are right – no matter how much we love them (I feel like there’s a parenting metaphor here). When they leave our brains and enter the world, all of our ideas must evolve and adjust rapidly. This transformation is core to the process of moving creativity into the realm of innovation. 2. Stay in the lab too long. One of the hardest experiences of my professional life was putting an early stage mobile app into the crucifyingly critical hands of teenagers (and I used to do community organizing!). To make matters worse, it was an app trying to connect them to their schools! It was a beat-down – for months. But, it was also the only way we were going to get feedback quickly and broadly enough to iterate on the product and better understand the problem we were trying to solve – the real problem of communication in schools. Our idea was wrong – but there was enough right to build on. It would have been a whole lot easier to say “no, it’s not ready” and keep developing out of fear of what we might hear if we let people actually use it. However, if you accept that you are even somewhat wrong, this continued protection and isolation of the laboratory is actually a sure-fire way to dig yourself and your product deeper and deeper into holes of wrongness, running at features and investing in ideas that get too big to turn around when the user’s truth finally becomes your reality. 3. Respond to user feature requests rather than user problems. Users will make requests of your product based on their experience using it and/or their knowledge and experience of any similar or complementary products. When we pivoted our mobile communication product from education to healthcare, we took the opportunity to reassess the communication problems our software was trying to solve in the new industry. At the heart of communication complaints from both physicians and administrators was email. It was too spammy. Not built for physician workflows. There was no data tracking. It was overrun by people you really wished didn’t have access to your email address. As we started to redesign and retool our product, we also started to get early user feedback. And, whether in focus groups or one-on-one meetings with early users, as we tried to understand their problems, people constantly asked for features that they believed would solve their problems. If we had built our software based on their ideas and feature requests, we would have built email almost exactly - and exactly as they complained about it. We had to dig much deeper to try and solve a problem and not just fulfill feature requests that would add up to a product they already said wasn’t working for them. 4. Sacrifice craftsmanship for expediency - or sacrifice expediency for craftsmanship You need to have both, and there is no easy answer for which one is right at any particular moment in your product development. It is a constant tradeoff, but one that in the long run needs to trend toward craftsmanship. Building something well so that it delivers speed, performance, reliability, and can scale will rarely come back and bite you. Delivering something that appears to do that but then crumbles just when those attributes are most critical for your users will at best breach your user’s trust in your product and at worst send them running toward a competitor who promises the same. A good team constantly battles out these tradeoffs, and it is in these battles that the various voices of sales, product, engineering, design, and whoever else should have the opportunity to communicate their perspectives and priorities. The more one voice or one perspective drives product design the more likely you are to sacrifice expediency and craftsmanship, one for the other.  In my last blog "Stop doing your part", I focused on building a do-what-it takes team. But, consider this the appended warning to that blog: you can’t just ask people to do what it takes as an excuse for not investing sufficiently in your strategy or improving your own leadership. So, as much as we want the do-what-it-takes attitude and we understand and celebrate the successes that such an attitude can generate, we need to check ourselves to make sure we aren’t burning people out. Just because one of our people can step up and do extraordinary work in a difficult situation doesn’t mean we should allow that situation to persist - or chronically resurface. Their extraordinary work should not become the ordinary expectation. Extraordinary individual effort is no more sustainable for driving successful teams over time than the do-my-part mentality that I discussed in the last blog. It leads to burnout and pushes our do-what-it-takes people to feel they are just being taken advantage of. It doesn’t take long for people to realize when they get recognized for doing great work simply by getting more work. So, we must think critically about why we find ourselves in situations that require extraordinary effort from our people. Is it strategy? Resourcing? Skills/team/work mismatches? Unreasonable expectations? Or, is our leadership perhaps fomenting unnecessarily harried working conditions? It is probably some of all of these as they tend to be interrelated. So, let’s celebrate our people for doing what it takes but build teams and organizations that aren’t always pushing them to the limit.  And start doing what it takes. Teams are complex social systems with emergent dynamics among members and emergent contexts in which they operate. This is true of small teams and only more so as teams grow. If people merely do their part, they are actually complicating things, forming a complicated system; and complicated systems are to complex work what the assembly line is to internet security. In dynamic and growth-oriented work environments, your “part” is always emerging, so as soon as you start just doing it then you probably aren’t fully doing it anymore. While you may be a high performer and may be surrounded by high performers, no mere collection of individual contributors will ever manifest in a sustainable, high-performing team doing complex work. A set of powerful parts will not inevitably make a powerful whole. In fact, the opposite is more likely true: the more powerful and simultaneously partitioned the individual contributors the less likely you are to build a powerful team that bridges them. The strength of the individual contributor mindset is too strong; the rationalization of the do-my-part mentality feeds itself and invites others to just do their part as well. As a result, as do-my-part teams grow, they become increasingly less adaptive and less effective in responding to the emergent dynamics within and around them. So, how do we build more complex teams and avoid complicated ones? How do we inspire more people to do what it takes? Hire for where you are going, not just where you are. We often think about hiring for “fit” with our team and/or organization. While this may seem to make sense in the immediate term, we should understand that “fit” is a temporary construct that belies the change inherent in a growth strategy. So, fit today could easily not fit the future. Consequently, we should hire and invest in people who will help us deliver and define an emergent future. We need team players and learners who will not just do the work but will help create and define it. Communicate the vision. If our people at all levels are going to do what it takes to define our collective future, they must be organized around and feel a sense of ownership of some collective vision. They should also understand (and it should be true) that they are helping define how that vision evolves as the team and market context also evolve. Team leaders need to communicate and actively invite input on the vision not merely to try to get our people aligned around it but to more quickly identify the people who don’t, and perhaps won’t ever, own it. Promote creative tension. I have written about creative tension in both of my books as I continue to try and flesh out my thinking on team power dynamics. For this blog, I’ll just share below the core components of relational tension and illustrate how they differ in environments of creative versus destructive tension. What to do when things don't go your way (because entrepreneurship isn't as sexy as you think)1/18/2018  Entrepreneurship is hot right now. It’s everywhere. It’s in the news and on TV. Shark Tank is looped all hours of the day. Colleges and universities are adding entrepreneurship courses for students across the liberal arts, and communities are creating centers to teach seemingly anyone how to make their vision a reality. Here’s what you’ve gotta do. Here’s what you’ve gotta have. Here’s who you need around you. It’s very exciting and a liberating time for creatives of all types. But, even with all of this, no one can tell you what is going to go wrong with your venture. They can prepare you to avoid unforced errors but obviously no one can predict the challenges you and your company specifically will face. And, let’s be honest, focusing on the ugly parts of entrepreneurship doesn’t sell books or TV adds, and tends not to inspire students to chase their dreams. As a result, few are investing in stories and strategies for the grind of iterative survival that for many, if not most, of us is at the heart of the entrepreneurial venture. As I reflect on my first for-profit startup, I’m amazed at how little actually went right. In fact, it seems almost nothing went right. Some of this was our fault, some of it was out of our control, and some of it was just part of being an entrepreneur. So, with some time and space to reflect, I am left to wonder: how did we make it? Here is a little color commentary to give some context for my wonderment: Very early, my partner was delivering a product demo for teachers at a high school where we were hoping to roll out our technology, and two teachers showed up in workout gear looking for the Zumba class. Our product and company were named Zeumo (‘zoo-mo’), and we were trying to help schools more easily and effectively communicate with and engage their students. The teachers left, mumbling their disinterest in our product demo, disappointed there was no Zumba class. About a year and a half later, Zeumo had pivoted industries into healthcare with the same value proposition: trying to help hospitals more easily and effectively communicate with and engage their physicians. I was doing a product demo for a group of physicians that had taken months to organize when a nurse rolled a cart into the already tight and windowless conference room and asked the physicians to line up to get their flu shots “while you listen to the demo.” My demo was literally going to be coupled with physical pain. We had made the pivot from education into healthcare on the premise of a partnership with a large healthcare company who loved our product and was trying to figure out how to communicate with their physicians. We worked with them for almost 8 months on a “joint venture” and remained patient but persistent as we tried to codify the “joint” part of that venture with financial, marketing, and legal commitments – all of which were very slow coming presumably due to their massive bureaucracy. As we approached the first roll out in one of their flagship hospitals, they finally delivered a pricing model that had us under water and a marketing “plan” that shifted from rollout out at 160 hospitals to “we will introduce you to a few of our CEOs.” It was pretty clear that they were going to hook us, starve us, and buy our technology for pennies when we ran out of cash – which wasn’t long, and they knew it. So, we (6 of us strong with no healthcare experience and little cash) walked away from one of the largest, most successful healthcare companies in the country. If we were going to die, we weren’t going to die like that. Another year later, when Zeumo was ultimately acquired by a different healthcare company, there was immediate rub within the new company with its product teams and marketers because they all believed they already had built the same technology as Zeumo. The acquisition apparently made little sense except to the people who had led it, and they were not a part of any of those teams. After some surprisingly complicated sleuthing on my part, much of it sadly with people with little knowledge of either product but resistance to ours, it turned out that the products couldn’t have been more different – the company’s product queried physician performance metrics and Zeumo was a mobile communication platform. But, there was a marketing story for the company’s product that included the idea of communicating those performance metrics with physicians. So, communication. Physicians. It must do the same thing as Zeumo, right? While ironing that out to try and get a better sense of buy-in from the new company, we were also exploring the opportunities to deliver on the value proposition of our acquisition – rolling out our communication platform for physicians but enriching it with the acquiring company’s research and data assets to deliver targeted content and drive physician utilization. To make another long story short, neither their research nor data were organized or stored in such a way that we could easily or reasonably distribute them through our communication tool. In fact, their sales and membership models, which organized their relationships to buyers, didn’t even support the cross-product concept at the time. So, at this point, the value proposition of our acquisition was deeply in question. Did I mention that we had built a nice little product that did exactly what it said it would do? The fact is that the variables involved in a successful venture are vast – some controllable and some not. And, the ideas for products and services we start with are always at least a little, and more likely a lot, wrong. For us, this was as true at the inception of our product as it was at the point of our acquisition. Figuring out what to do when stuff goes wrong is, at least in my experience, the core to becoming a successful entrepreneur. And, I should note that this is a universal truth from my work as an artist, an organizer, a consultant, and in nonprofit leadership. So, what do we do when things don’t go our way? 1. Understand why – identify the problem

2. Develop a strategy for the next iteration

3. Be fast but stay disciplined

Keep your team aligned

Communicate, communicate, communicate

In reality, the questions, steps, and processes offered here for when things don’t go your way should just become a part of how you do your business daily. If they do, you will always be ready when things go wrong and won’t have to wonder how you will respond if they do. Image: https://www.munich-business-school.de/insights/en/2016/lean-startup/  excerpted from Creating Matters: Reflections on Art, Business, and Life (so far) Sometimes our “finished” work can actually be what prevents us from creating new work. We get stuck. We stop listening. We stop learning. As artists and creators, we often believe our work is inherently precious and valuable and meaningful because…well… it is to us. Well, it’s not. And, thinking so is a trap and counter to the idea of the creative process. The most important lesson I learned as a developing artist was accidental, and if I hadn’t been forced into it, I would have almost certainly continued to hang on to my every “masterpiece.” I had never built anything. I had never worked in a woodshop. I don’t measure things particularly well, and don’t pay that much attention to detail. So, building things was not exactly in my creative wheelhouse. So, of course, when I decided to build something in my first sculpture class, I went big. I’ll spare you the details of my early efforts at conceptual art, but the piece did make it into the student show! Enter ego: Yes, I am Artist. Brilliance. Can you feel that!? I went home for the summer while the Student Show wrapped up and when I came back, there was my masterpiece, sitting in the hallway. As I stood looking at it, one of my teachers approached and said: “You have to get that out of here.” Apparently, everyone didn’t feel it should be a permanent installation in the studio hallway. And, apparently, it didn’t fit through any doorways I could reasonably get to. Hmm…what to do!? The answer was back in the sculpture studio, where it all began…and, it was a “saws-all”. After the initial horror of the thought of destroying my piece, I plugged in the saw and gingerly started to cut. Within moments, I must have looked like the artist version of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre. I ripped that thing to pieces…sawing…splintering…crashing…cutting…and almost certainly bleeding. And, in the final act of destruction, I dragged my masterpiece piece-by-piece outside and slung it over the side of the dumpster. Holy crap that felt good. It was humbling…and then completely liberating! I have created more freely since that day. Fast forward fifteen years or so, and I was helping start Zeumo. While we were still struggling to get distribution in a number of large school districts, we were presented with a new opportunity: “We need this kind of app in hospitals.” We were failing slowly in education and had to be humble enough to acknowledge it. We also had to have the courage to try something else, to keep iterating. Long story short, we seized the opportunity and, having invested countless hours and hundreds of thousands of dollars with a vision for helping high school students, we took the proverbial saws-all to the education app. Humility is not about accepting loss or defeat. Humility is about owning the process of exploration and finding the strength and energy to keep doing it. It’s about putting failure in its proper place in our art and in our lives – right at the heart of what we are creating. When we started Zeumo about three years ago, we believed “we can do better.” And, we still believe that we can do better at communicating with and engaging high school students than P.A. systems, posters, flyers, and emails they never check. We believe we can do better than having all of a student’s in-school and out-of-school activities using different communication platforms, leaving a student with 6-8 logins and passwords just to remain up to date and involved.

After a few pilots and a year-and-a-half struggle to turn interest into contracts in a crowded, “freemium” education technology market, someone in the healthcare industry saw our product. “Hey! We need this for physicians!” As a startup trying to survive and build a viable business, we thought perhaps “we can do better” in another industry. (Anything is better than dying slow death.) We spent 8 months navigating a joint venture with a large healthcare company. Days before rollout, and with the joint venture not finalized, things began to devolve as the details of their go-to-market plan and pricing became clearer. This wasn’t going to be a good deal for Zeumo. So, our team had to step away. Even though we were burning cash and still trying to make a full pivot into healthcare, we had to believe “we can do better.” And, after many more months, some additional investment, and several pilots of our own, we understood more clearly the challenges of the healthcare market. The sales cycle is long. The bureaucracy is deep. The leadership dispersed. Not to mention, no one on our team is a healthcare expert! We believe in our technology and still believe that with the right healthcare partner “we can do better.” For that reason, I am pleased today to share that Zeumo is now part of the Advisory Board Company whose healthcare expertise, consulting, and other technologies mean we will do better. It is funny how this refrain has resurfaced to summarize the moves and the motivations that have driven our little startup, now 7 people strong, hustling every day trying to make it, trying to do better. And yet, as I consider it further, this belief that “we can do better” is surely core to all innovation and a driver of critical thought and creativity regardless of context. It is the belief that sustains persistent, decades-long legal battles for justice and equality. It is the belief that drives the teacher who transforms her classroom from a space for education to a laboratory for learning. It is the belief that gets you up in the morning and says that there is something new to be accomplished today. It has been a crazy three years. Exhausting. Stressful. Eye opening. And, I still believe we can do better. I hope wherever you are and whatever you do, you believe it too. Many years ago, I learned a training/facilitation protocol we simply call Comfort/Risk/Danger.

When working with a team, the protocol helps them, based loosely around whatever it is they are trying to accomplish and what kind of work it entails, to share what things put them as individuals in the comfort zone, the risk zone, or the danger zone. For instance, some team members will be totally comfortable with public speaking; for others, it feels dangerous. For some, crunching numbers is comfortable; for others, it would be a risk. Some find conflict dangerous; some find it risky. And, we all know those who are a little too comfortable with it. But, we need speakers; we need numbers people; we need people who create, manage, and support effective conflict. And, we cannot afford for those skill sets to reside with one person or in one department. It’s too easy for them to get marginalized, or to go away completely. Some element of each has to be part of a broader culture. So, as the protocol helps demonstrate, building an effective team cannot just be about capitalizing on what everyone is already good at (i.e. what puts them in the comfort zone). Creating a team is about learning how to support a pervasive element of risk. Humans learn better when there is some level of risk. In the risk zone, we are stretching, challenging ourselves, and actively asking questions and seeking solutions. When we are comfortable, on the other hand, we are surrounded by what we already know. We aren’t actively learning. When we are in danger, we aren’t learning either (social, emotional, and professional danger; not just physical). Fight or flight kicks in. We shut down, seek relief, and avoid (or project our danger onto others). After starting in education, Zeumo has now pivoted to be a mobile solution for hospital communications. As we line up our new sites and support the teams who are rolling it out, Comfort/Risk/Danger are in play for all involved. How do we launch a new product in a new market in a way that doesn’t put those of us at Zeumo in danger? How do we support each other’s risk in advancing the product, learning from our early clients, and lining up future sales? How do we offer a new mobile communication technology for hospitals that doesn’t put physicians, nurses, or hospital administration in danger? How do we best support them as they address their own systemic communication challenges? How do we help improve communications and communication workflows as risk, not as danger? How do we articulate, and present through our product, sufficient value and ease of use that adoption seems obvious and the learning curve is relatively flat? The problem of communication in hospitals is clear and has been identified and acknowledged by every leader we have spoken with: too many channels; too much noise; too little strategy. The challenge of implementation, assuming the technology works (which it does), largely rests in the culture of learning in the hospital and facilitated by hospital leadership. To create such a culture, to be such a leader, and to leverage new technologies – to be a learning organization – is just risky. I was on my way back from a long one-day trip to Phoenix (doing the startup hustle) and an old friend popped into my mind.

Scot is a musician. He was in a band. And, they were very close to making it big. They got airplay across the country and internationally. They had a die-hard local following. (I was a fan before I ever met him.) They were traveling all over the place building strong pockets of fans everywhere they put on their incredible live shows. They were hustling. Momentum was building. But, they didn’t become “rock stars.” Knowing Scot, I am not sure that is even what he wanted. I suspect the rock star designation for most musicians is an inaccurate, or at least narrow, moniker to try and capture some external notion of success or validation. Scot loved music. He loved the camaraderie of the band. He loved performing. He loved creating. He loved that people loved what he was creating. And, now years later as a college professor, he still does. Little has really changed. Scot’s creativity didn’t live within his music. Music was its outlet. Now, it’s higher education. For years, people have chuckled in confusion when I tell them I have an MFA (that I am still paying for) from one of the most respected, if not widely known, art schools in the country, Cranbrook Academy of Art. Clearly, I wasted my time and money. They assume I was forced to change “careers” because art was obviously a dead end. What could art have to do with my work? With education reform? Entrepreneurship? Well, everything. Creativity is a transferable skill; the creative process a discipline. Where and how we choose to cultivate our creativity is fairly unimportant. However, where and how we choose to apply our creativity directs our life’s creative journey. Now, as an entrepreneur I feel more than ever like Scot (or how I imagine him early in his music career), like a musician hustling to get his product out there. I want to share it with people. I want people to use it. Give feedback. Enjoy it. Challenge it. Find meaning in it. And, yes, pay for it. I want all of this so that I can continue to create in this space. But, I also want to know what I am creating matters. And, if it doesn’t, I want to know how and why so that I can make sure it ultimately does. Like most artists, musicians, entrepreneurs, and the various and sundry others with the driving need to create, I don’t really want to be a rock star. I want to matter. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed