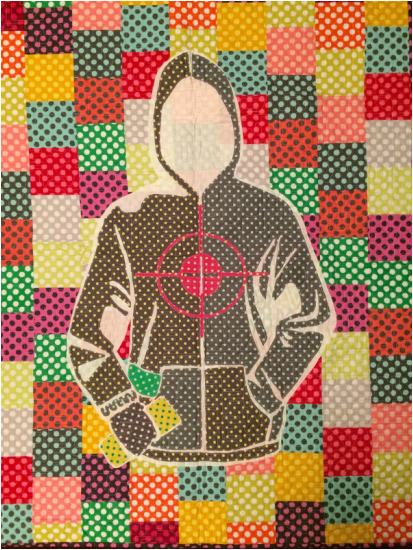

As a child, I went to bed every night wrapped in the warmth and weight of a quilt made by my grandmother. I would lay there in my bed, the street light beaming in, and, at least a couple nights a week, listen to gunfire coming from outside my window, sometimes three blocks to the north, sometimes three to the south. Sometimes, the shots would be one or two quick pops. Other times, I could hear an exchange back and forth, the slightly different cadences my only description of the shooting parties. Mostly, they ended in silence, at least from where I was. Occasionally, it was rapid fire and might quickly be followed by squealing tires or sirens in the distance. I didn’t know what was happening. I didn’t know who was shooting at whom, or why. I didn’t know who died, who lived. I was in bed, under my quilt, held in my grandmother’s hands, safely within the walls of my parents’ home. The pattern on my chest was a series of squares and triangles, not concentric circles. Even then, thanks to my parents, I knew I was fortunate. The patchwork of my life would be one of selecting and piecing opportunities together, not searching for mere scraps to cover me or help me survive the day. When I walked out the door, or went to the community center, or played in the park, my peers, despite living in close proximity, experienced a very different life than I. Their patterns and patchworks were not the same as mine – although their basic adolescent needs were. Love. Safety. Warmth. Connection. While I technically knew my own privilege, I don’t believe at the time my mind could actually understand the depth of our different lives. I don’t think I could conceptualize fully what the opposite of privilege really was in my community. My peers and I were friends on the playground, equals on the basketball court, teammates on the baseball diamond. Then, just as I was about to go to college, one of my friends and teammates was shot and killed at a party, a friend who had made it to college, earned a scholarship, home for the summer. And, while his death was an accident, I was shocked into a realization of how little I knew or understood about the world immediately around me. It wrecked me. I knew I wasn’t going to parties where there were guns that could accidentally go off. But, I finally realized how many of my friends were. I finally realized that for reasons of race, class, family history, and much more, guns were a part of too many lives. They were no longer off in the distance. I was no longer wrapped in my grandmother’s quilt. Years later, when I came home from art school, and began working with teens from this same community, I learned this lesson again in even more real ways. I would read in the paper one morning about a 15 year old getting shot, and find out in the afternoon that one of my young people watched it happen, knew the shooter and the victim. I had discussions with youth in gangs and those who weren’t who educated me on the rules of the game in their neighborhood, and if you knew the rules, you were probably safe. I even had one young man I worked with, a couple years after I had last seen him, end up in jail for murder. He shot someone, another young man. There were no signs at all of this future when we worked together. I was stunned, and still can’t fully process it. And, as my neighborhood gentrifies, as I raise my daughters in the same home I grew up in, I feel the increased tension, the hyper awareness, the palpable fear as the 3 blocks north and south get further and further away from the gentrified world of the island in between. While there have been no acts of violence that I know of akin to Trayvon Martin, the tensions should be understood as the same. Violence creates fear. Fear ends up in violence. Fear of the young black male, the one in the black hoodie. Violence is poverty. Violence is a lack of education. Violence is a lack of communication. Violence is a lack of relationships. Violence, as civil rights icon Dr. Bernard Lafayette says, is the language of the inarticulate. So, can art be one language to help us move beyond violence? The tension and sadness and frustration and confusion that Thomas Knauer forces us to look at in his quilt summarize, in so many ways, the story of my life, my privilege, my exposure to brutal realities not my own, my constant wrestling with what I am supposed to do with it all. What does it mean to be white? To be privileged? To be educated? To be an artist? To aspire to leave a positive mark on the world around me? I have no doubt that if we are going to have the conversations and build the connections we need to move beyond a culture of violence that art must be at the center, bold art, thoughtful artists. We need artists to help present our world and our images and our languages and symbols back to us in ways that force us to think critically about them again, force us into a new relationship with them. Perhaps the warmth and weight of this activist quilt from Knauer can provide a moment of safety for each of us to reflect on the challenge of violence for ourselves, to inspire us to explore how we might become part of the solution. This is just my first reflection inspired by this work. I am sure to have many more. That’s what art does. Check out more of Thomas Knauer’s work at www.thomasknauersews.com

1 Comment

Linda Kurella

8/17/2017 12:55:00 pm

Thank you for your story. Thomas always gets right to the heart of a situation.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed