Your ability to lead change is already being tested, even if you don't think you're leading change9/25/2017 Change isn’t what it used to be, neither are our organizations nor the environments in which we work and compete.

Change is no longer a discreet organizational development concept: what are the structures, policies, and practices that need changing (mostly from the top) to accomplish our business goals? Change is emergent: how do we systematically identify the needs, gather the insights, and prepare and empower our people at all levels to make it happen? Emergent change and our ability to respond to it must be cultivated as part of our cultures, core to the people we recruit and hire, intrinsic to how we develop and support our existing people, and strategically aligned with our business model. Despite this reality, it seems that most of the “best-selling” approaches for leading or managing change make the concept seem formulaic and finite rather than dynamic and perpetual. They make it seem organizational rather than relational. Even as many of these models readily identify change as the only constant in our contemporary business environment, they often present solutions as if it were time bound and discreet. One of the most popular is the Kotter Change Model, which defines an 8-step process for leading successful change: 1. Create a sense of urgency. 2. Build a powerful coalition. 3. Create a vision for change. 4. Communicate the vision. 5. Empower action by removing barriers. 6. Generate short-term wins. 7. Build on the change. 8. Make it stick. I don’t actually disagree with any of this and totally understand how such a list makes a powerful product for those who are struggling to lead change. I wonder, however, if those struggling the most to lead change aren’t often the ones who need a deeper understanding of it. Yes, in most cases, you will need to take Kotter’s steps to achieve the change you want, but is that all it takes? I don’t think so. You know what will kill your change process before you ever take that first step? 1. A lack of trust in leadership. 2. Poor relationships with and among our people. 3. Ineffective communication from the highest level of values and vision down to day-to-day operations. Let’s consider some basic questions:

I think for most of us the answer is at least “not likely” for all of these – which undermines the first four steps in the 8-step change process! So, while I appreciate the concise steps for change provided by Kotter’s model and others that are equally consumable, they mostly represent the tactical investments that live on the tail end of any real change process. They ignore foundational concepts of readiness. If I might adapt the old adage: “Change is 90% preparation, 10% perspiration.” The 8-steps are mostly the perspiration. As leaders, we have to be mindful every day and in every interaction of what kind of organization we are building. We have to understand our power to engage and influence our people, to share power with them, and to prepare them to help lead and navigate change with us. We must work daily to generate energy and ownership of our vision, strategies, and work with others. As leaders, we have to be willing to do the immeasurable and un-measureable work of building trust, modeling strong relationships, and investing in culture. If we do this work, we, and our organizations, will be ready for change as it comes. It will just be part of how we do business.

0 Comments

Power is at the core of your organizational culture whether or not you accept or even recognize it. In fact, if you don’t accept or recognize it, it’s likely that you are the one benefiting from it. You’re “in power”. Regardless of whether you do or not, I promise that others see it, and they see you through it. So, the question is: are you the facilitator of a powerful culture or are you progenitor of a culture of power? Understanding the difference and how your people interpret your culture, and your position as a leader in it, will determine the nature and effectiveness (or not) of your leadership over the long term. Here are a few distinctions that might help clarify: A powerful culture believes in its people. A culture of power believes in the system, structure, and organization. A powerful culture grows power. A culture of power consolidates and organizes it. A powerful culture believes that knowledge and ideas are everywhere in your organization. A culture of power believes that knowledge and ideas come from the top. A powerful culture celebrates people at all levels. A culture of power celebrates a select few. A powerful culture focuses on relationships, responsibility, and accountability. A culture of power focuses on accountability. A powerful culture seeks transparency. A culture of power keeps secrets. A powerful culture communicates. A culture of power distributes information. In a powerful culture, our people feel a sense of ownership for their work. In a culture of power, work feels directive and even compulsory. In a powerful culture, there is joy. In a culture of power, there is fear. In a powerful culture, everyone feels responsible for leading and following. In a culture of power, there are a few leaders and many followers. In a powerful culture, everyone teaches and learns. In a culture of power, some are teachers and others are learners. In a powerful culture, leadership is emergent. In a culture of power, leadership is constructed. In a powerful culture, change is both bottom-up and top-down. In a culture of power, change is top-down. In a powerful culture, people naturally create. In a culture of power, people wait for others “above them” to create. In a powerful culture, people are proactive. In a culture of power, people are reactive. In a powerful culture, people seek truth. In a culture of power, people seek affirmation. Image: http://www.hci.org/blog/how-encourage-innovation-and-mitigate-risk-start-organizational-culture Reposting a blog about my book Creating Matters: Reflections on Art, Business, and Life (so far) originally posted here by Seton Catholic Schools' Chief Academic Officer William H. Hughes Ph.D. Anderson William’s book Creating Matters is gaining traction. We are using Creating Matters as a guide in the development of the Seton Catholic Schools Academic Team.

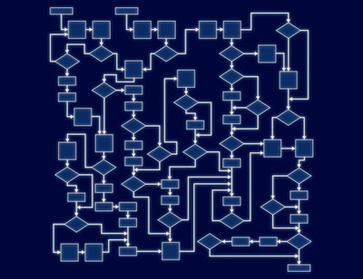

Creating Matters is helping us to think differently about our work as educators: our priorities, relationships, and what we are creating – in this case high performing schools and effective leaders. The world has always belonged to learners. Creating, building creative relationships, and purposefully reflecting can generate continuous learning and help us think differently about transforming a school, a business or one’s life. We have to think differently or we won’t grow and understand the changing world around us. Lifelong learning opens our minds exposes us to new vantage points, more things to see, to touch, to explore. Lifelong learning is hard work. It is not for everyone, but for those who commit, the joy and engagement makes one’s life better. To sustain lifelong learning, we must depend on our creativity. Creativity defines the nature of our relationships. It puts our learning into action. It is a philosophy of how we see the world and our role in it. Creativity will determine whether our efforts will ultimately create impact, whether we transform schools and build new leaders, and pass that work to a new generation. Creating anything new starts with asking questions: questioning the perceptions of the others, the sources of accepted fact; the thinking that verified it; and how we rethink the work of transforming schools from scratch. Too many schools and districts are great examples of organizations that have failed over time to recreate themselves while convincing themselves they are better than the facts show. In the case of Seton Catholic Schools, Creating Matters guides us in creating with a focus on what kids should be learning and becoming: creative, lifelong learners who are ready to change and engage in their community. Isn’t that what schools are charged with doing? Schools in transformation must ask this question: If we are starting from scratch and wanted the kids to become lifelong learners, is what we are doing now what we would design from scratch? Answering this question and wrestling with its implications require us to be more creative, to have stronger relationships that survive the necessary arguments and conflicts, and to build our work on a model of creating rather than constantly fixing. At Seton, we are seeing some bright spots in teaching and learning along with better student engagement with faculty who are starting from scratch. We are collectively creating and questioning our own assumptions, learning new skills and creating lifelong learning across our school community. When we bring this shared purpose and focus to our classrooms and students, the transformation is palpable. We are building a community of students, faculty and staff who are committing to lifelong learning and to creating the kinds of schools where that commitment is put into practice. Read Creating Matters and then put it into practice. This isn’t about “seven easy steps to a better you” or some other seemingly simple approach to creativity or leadership. It’s about renewing your awareness of who you are and what you can do when you commit to creating what matters in school, business, or most importantly, life.  Years ago, while commiserating about limited access to higher education for low-wealth students, a colleague offered a thought: “Every system is perfectly designed to deliver the outcomes it delivers.” If you think on that for just a moment…(go ahead, do it!)…it’s both painfully obvious and painfully…well…painful. But, for anyone working to change the outcomes that are important to them in education, politics, justice, or otherwise, this simple statement tells us where our efforts must be directed: the systems that we have, advertently or inadvertently, designed to underperform (or to perform exceptionally toward outcomes we never intended). Under this premise, the school system that is struggling with dropouts is perfectly designed to generate those dropouts. The justice system that incarcerates men of color at dramatically higher rates than anyone else is perfectly designed to incarcerate men of color. The political system that generates corruption, gridlock, and weak candidates is perfectly designed to do just that. System performance is not the sum of its individual elements. It is the interrelated (systemic) performance of its elements. Systems get misaligned because we build and invest (or disinvest) in them element by element often over long periods of time, and amidst shifting values and visions. And, the more we address individual elements in isolation the more likely we are to create systemic dissonance (the type of boiling-frog dissonance we actually grow to accept). Within an organizational system, for example, perhaps we have rewritten our values statement, but our organizational structure is out-of-date or even arbitrary. We revisit our investments (budget, people, etc.), but align them with our organizational structure rather than our strategy (this is my new definition of bureaucracy, by the way). We clarify and document our desired outcomes, but we maintain old strategies that have lost relevance in a changing environment. We improve our product or service delivery, but never invest in our human capital pipeline to support and sustain it. When we see systemic failure, we cannot blame the system without owning our role in it. We cannot claim that our part of the system is working, and it’s everyone else’s that’s broken. We cannot do fragmented and narrow work and believe it will add up to a healthy system. It won’t. If we are going to create the system that is perfectly designed to deliver the outcomes we actually want, we need to design, invest, and lead systemically. image: http://www.intelligencesquaredus.org/ I have written previously about hospitals thinking of physicians as customers. While it is not a perfect match, there is something important to be learned from the approach.

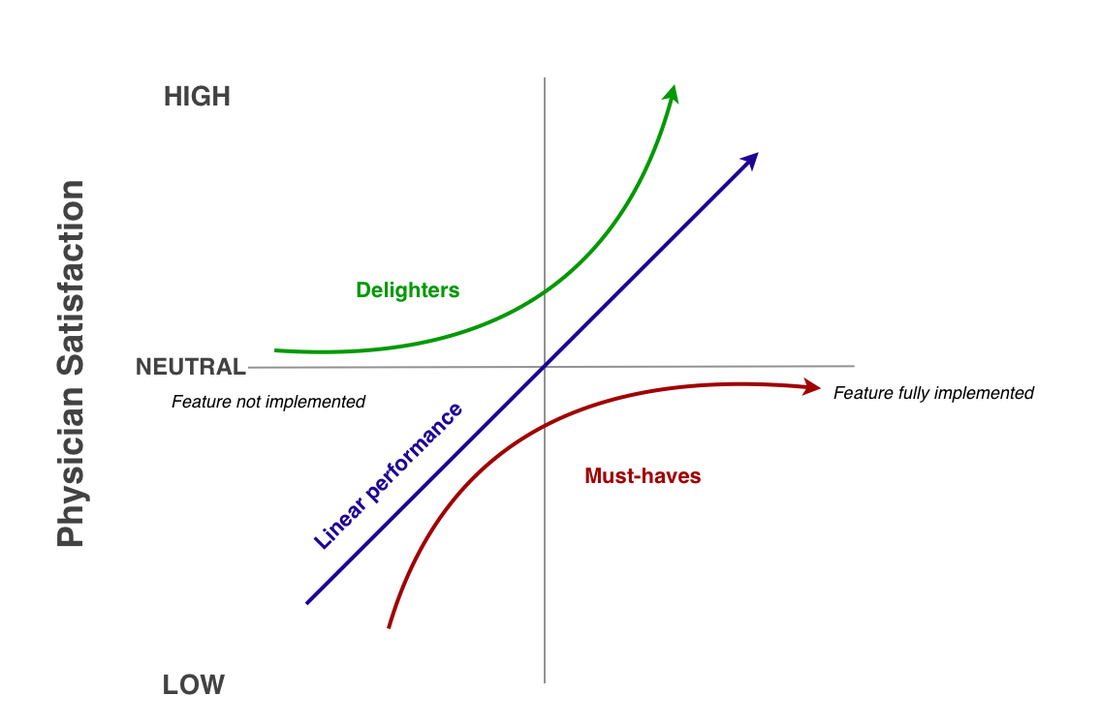

With that in mind, I was reading recently about the Kano Model of customer satisfaction, and believe it provides a framework for understanding strategic investments in physician satisfaction and engagement. While the model is layered, in its basic form (summarized in the image below) it asks: 1. What are the “must-have” features when it comes to physician expectations of your hospital? These are also considered threshold features. And, no matter how much of a must-have feature is added, satisfaction never rises above neutral. 2. What are the “the-more-the-better” features of your hospital? These are linear features. And, as the name suggests, physician satisfaction is correlated linearly with the quantity of the feature. 3. What are the “delighter” features of your hospital? These are the features that provide the greatest satisfaction and differentiate you as a premium place to work, or to do work, for physicians. But, the lack of a delighter will never decrease physician satisfaction below neutral. 1. What do you need physicians to know?

This is about business strategy. For you to lead a safe, productive, successful hospital, what do your physicians need to know from you, or about the hospital more generally? What information is going to help align and engage physicians with the vision and direction of your hospital? What will make the hospital safer, with healthier and happier patients? When you think about hospital – physician communication, this question is fundamental. 2. What do physicians want to know? Knowing what physicians want to know and delivering it is crucial to physician engagement. It’s about professional respect. Do physicians care about hearing from the CEO or CMO? Do they want updates on policy changes and healthcare reform? Do they care about overall performance of the hospital? Are they looking for CME opportunities? Strategic internal communication has to be two-way and engage the wants and needs of both hospitals and physicians. 3. What do physicians want/need you to know? To reiterate, communication is two-way, not just in the nature and value of the content exchanged but also in who gets to initiate it. It’s about listening as much as it is about talking, posting, sending, and faxing. So, at your hospital, who gets to share information? Request information? Seek/give feedback? Report on or provide updates on hospital successes? Challenges? Who listens? Physicians need avenues to communicate with hospital leadership, to know they have been heard, and to know it matters. If they are going to engage in the vision and mission of your hospital, then they have to have a role in leading it. 4. What are you willing to change? Poor communication leads to low physician engagement. Low engagement creates communication problems. So, something has to change. What is it? What are you willing to stop that you know isn’t working? What are you wasting time, energy, and money on (ex: email newsletters with 15 pdf attachments, faxes, posters in the lounge)? What workflows need to be evaluated? What roles and expectations must change for physician support staff? For hospital executives? For physicians? Communication both creates and is a function of staffing and workflow models. So, if you want to change communication, then you must be willing to change these. Another new channel, new FTE, or new piece of technology on top of the same old practices simply won’t do it. 5. Why does it matter? If you are going to invest in change and expend your leadership capital to do so, you need a plan to articulate and promote “why” and then capture and report on the results. Can you reduce the volume of emails to a physician? Can you eliminate technologies or practices you know aren’t working anyway? Can you reduce physician stress or frustration? Can you create new feedback channels? Can you increase physicians’ sense of connection and engagement with your hospital? Communication impacts everything you do. So, pick short-term metrics that you and your physicians value and strategically align your communication change efforts to improve them. In the mid and long terms, you can then track lagging metrics like reduced turnover, increased engagement, higher productivity, increased safety and the like.  A mere 47 years after being coined, “Conway’s Law” was just introduced to me this week. It states: Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure. Sit with that for a minute. Reflect on systems your organization has designed: staffing, technologies, workflows, data management, reporting, and so on. Now, consider the communication structures of your organization (poor, partial, siloed, or nil still represents a structure). So why is this “law” so profound, and frustrating? 1. It’s counterintuitive. Communication structures determine system development; they don’t just facilitate it. We typically regard communication as a de facto point of process, sometimes intentional, sometimes not, that supports or inhibits our work. It just happens. It’s a conduit. A medium. It’s a means to an end. Maybe it’s even a workaround. Conway’s Law, however, suggests that rather than being merely a means, our communication determines our end; not just its success or failure, but the actual design. 2. It demands a different level of awareness. We are part of the organizational structure trying to change the structure that we are still actively creating. Communication typically functions on a default setting, or perhaps more accurately, an amalgamation of default settings within complex organizations. For most of us, it lives and functions below the level of consciousness, or at least intentionality. As such, we are simultaneously passive creators and active victims of our own communication structures – and according to Conway’s Law, therefore, the other systems we are creating. 3. We’ve wasted a lot of time and resources. Change efforts that don’t start with addressing communication structures will be marginal – i.e. not systemic. This is one reason why most of us have been frustrated by the organizational change attempts we have experienced. Communicating is not just about the message of change or the charismatic delivery of an idea by a strong leader. It’s about the process of communication, the structure on which the change must happen over time. And, few of us, in all of our change efforts, have invested deeply in our communication structures. I would love to follow this brief reflection with a handy and insightful list of 3-5 good recommendations for action. But, the reality is, if we go back to Conway’s Law, there is one recommendation for any organization: Start with communication! This is the first question hospital and system leaders who are struggling with physician satisfaction and engagement need to ask themselves. Really, honestly, what is your relationship…today?

And, you need to respond with more than a simple “it’s bad” or “we do great” kind of answer. You need to do more than quote annual survey results. If you believe it is important, then you need to understand it deeply. If money were disappearing from your books, you would investigate, audit, and scrutinize your accounting. You certainly wouldn’t accept vagaries or wait for the results of an annual survey! Question 2: What do you need your relationship with physicians to be? In other words, to deliver quality care, build an effective culture, and produce strong, bottom-line results, what does your relationship with your physicians need to look like? How do you satisfy them and the needs of the hospital or system simultaneously? Your relationships are either a bottleneck or a gateway to your performance. They are a part of everything you do. Question 3: What do you want your relationship with physicians to be? As a leader, you can choose to invest in relationships that are transactional and fulfill the basic requirements of your hospital or system. Or, you can invest in relationships that will help you build your hospital or system, engaging and leveraging physicians as key partners, influencers, and leaders in the work. You have to start with what you actually want. Question 4: What are you willing to invest, change? Everybody talks about physician satisfaction and engagement and how important they are to hospital performance and patient outcomes. Yet, few leaders systematically and strategically invest in them as core processes of the organization. It’s not just about physician support FTEs or whether or not physicians can text you their complaints in the middle of the night, but about philosophy and approach. It’s about investing in strong physician relationships as fundamental to how you do business. How you answer these questions will in part determine how physicians will respond to you: “When physician engagement and satisfaction are both high, physicians act as “dedicated partners,” when only engagement is high they act as “discontented colleagues,” when only satisfaction is high they act as “satisfied spectators,” and when both engagement and satisfaction are low they act as “distanced patrons” (Press Ganey). Which are your physicians? I attended a healthcare technology event recently where a hospital CEO told the audience: “physicians are an extension of your brand.” While I liked the clarity of the statement, I felt it only represented part of the unique and complicated relationship between physicians and “the brand.”

As a hospital or a healthcare system, your physicians are more than an extension of your brand; they are consumers of it. And, this dual relationship is critical to understand as you seek to satisfy, engage, align, and whatever else you want to do in partnership with physicians to increase performance. Before they can become an extension of your brand, or at least an extension of what you want your brand to be, physicians must be treated like your consumers. So, as with any product or service, you need to effectively market who you are, what you offer, and why you align with their existing values and goals (not just hope that they align with yours). If patients are consumers of healthcare, then physicians, in many ways, are consumers of healthcare organizations. As a cultivated and dedicated consumer, a physician can become an extension of the brand you are seeking to build. (They already extend the brand: good, bad, or otherwise.) You need physicians to share your values, vision, and understand your direction. In turn, you provide the tools and supports for them to deliver on them. Physicians should feel a personal connection with the brand and other high-level leaders within the organization who represent it. Here are a few recommendations for cultivating the physician brand consumer/extension: Identify what your brand is – internally – and market it.Marketing campaigns are typically focused on reaching consumers outside of the hospital or system. For the physician consumer, however, your message is almost certainly different than the one targeting the public (albeit ideally consistent from a values perspective). If you understand and believe in the physician-as-consumer, you must commit to strong and consistent internal messaging and marketing. Connect performance and brand.Good hospital performance means a lot of things: healthy patient outcomes, positive patient experiences, increased safety, lower stress, and a strong bottom line. All of these have an impact at the individual level, but cumulatively they build a powerful brand that people at all levels want to be a part of. So, your branding internally is not about taglines, it’s about values and your collective ability to deliver on those. Communicate your brand strategically and consistently.Your communication both creates and reflects the relationships you have with your physicians. So, if it is noisy and sporadic and only tactical or transactional, that’s the kind of relationship you will build with physicians. None of us is committed to a brand, whether it’s technology, tennis shoes, or a hospital, that communicates this way. And, if you choose to, your physicians probably won’t commit to you either. If you want your people to trust your communication:

1. Make sure the information is accurate and timely. If the company newsletter simply summarizes what’s already being talked about in the cafeteria, around the water cooler, or on countless internal email chains, then it is certainly not building trust in the company or it’s ability to communicate with its people. In fact, it’s probably hurting trust. You’re too late and as a result probably already behind the information curve. Your people will go elsewhere if they really want to know what’s up. 2. Make sure it is clear and relevant. If you send me the 500-word email that has 3 pdf attachments and bury what you want or expect me to do with the information somewhere in the middle, I’m either going to miss something important or realize you don’t know, or care, what is important to me because you sent me something seemingly useless. Either way, you are diminishing the value and impact of all of your future communications by sending confusing, overwhelming, and irrelevant ones today. 3. Find the right frequency, dose, and delivery. Different people work in different ways. Different jobs require the use of different communication channels. Understanding the right amount of communication and the right medium is critical to demonstrating an understanding of the recipient and his role in the company. For instance, an email to an administrator gets served differently than an email to a front-line employee who is on his feet all day. So, 50 emails in a day may not be a big deal for the former and completely overwhelming and unworkable for the latter. If you want to communicate trust: 1. Listen, and prove you are listening. If your people don’t think you are listening, then it may not matter even if you are. Yes, first you have to listen, but you also have to demonstrate to your people that they have been heard. This does not always mean that you do their bidding, but you acknowledge their insights and explain, if necessary, why you chose to do something different. People are far more distrustful if they think they aren’t being listened to than if they realize there was just a difference of opinion. 2. Credit ideas and insights intentionally and frequently. Anywhere possible, good leaders attribute their actions to the insights and guidance of others. Show and tell your people how they are influencing and leading the organization. A good leader knows it is more important to have his people securely behind him than his ego securely in front of him. 3. Seek input on strategic, operational, perceptual, and tactical issues. People distrust when they only get to provide input on marginal or relatively unimportant things. They also don’t love it when they only get asked for input when some outside consultant is helping facilitate a big strategic plan or vision session. Finding ways for clear and consistent feedback channels on a range of topics will not only build trust but also ensure you have all of the insights you need to make good decisions. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed